Vice is a loud, long, exhausting movie about the political career and aggressive corruption of Dick Cheney, a Lord of Misrule in American government so unbelievably, boundlessly, cartoonishly evil in real life that history might always be in danger of fielding accusations that it has embellished or fictionalized him in retrospect.

The canyons of Cheney’s wickedness are well-suited for satirical condemnation, and Adam McKay, the filmmaker behind The Big Short, the recent frenetic and didactic portrait of the 2008 financial crisis, seems enthusiastic about taking Cheney to task. McKay certainly pulls no punches in his indictment, but there are many moments when he might have reined things in. As it is, the movie misses some big opportunities and is distracted by other, unnecessary (and sometimes counterproductive) preoccupations. This is a strange and alienating result, considering the film so often squarely hits its target. But it should not be so tremendously convinced that it has stylishly knocked the ball out of the park every single time.

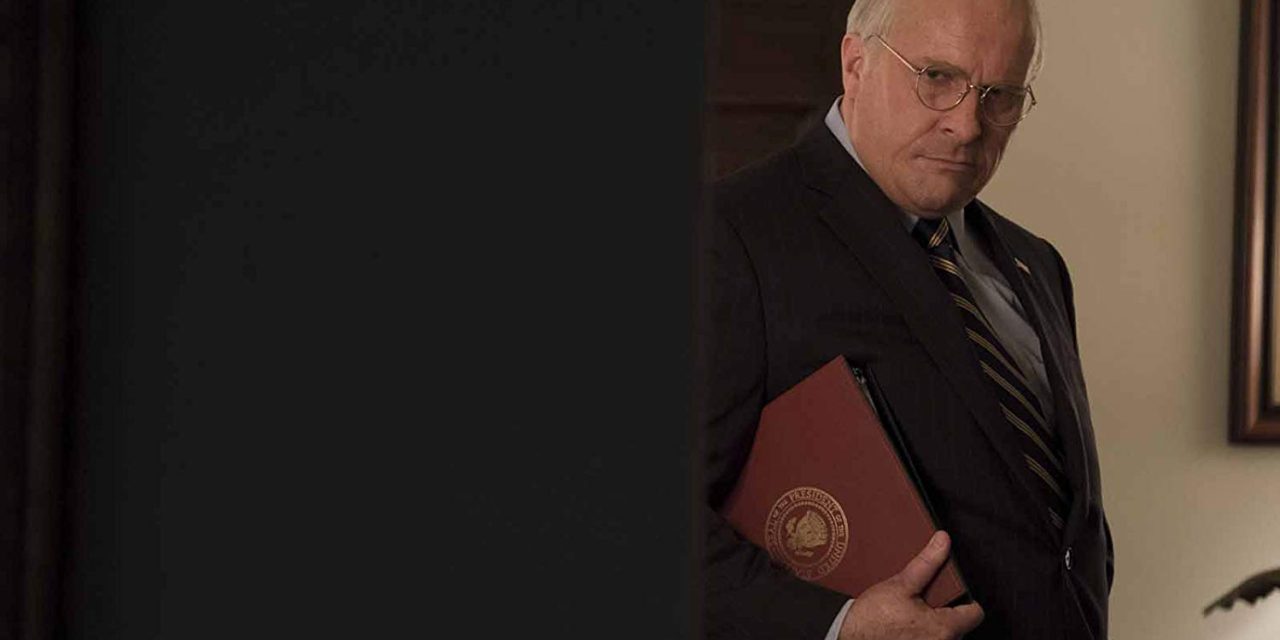

The best thing about the movie is its title. The second best is the prosthetic makeup work on its lead. Christian Bale (barely recognizable in a new body type, as he seems to like it) plays Cheney at various stages of his life. The film begins before Cheney goes to Washington, when he’s a stiff, drunk Yale-flunk-out living in the middle of Wyoming, hanging power lines for a living and disappointing his longtime girlfriend Lynne (Amy Adams). After an ultimatum from Lynne, he eventually shapes up, graduates from college, and winds up at the Congressional Internship program, where he becomes an enamored lackey to a wisecracking Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carrell). The two quickly become friends, with Cheney embracing and amping up many of Rumsfeld’s positions, creatively plotting to ensure his own success along with that of his wealthy friends.

The first half of the film is about Cheney’s rise to power and prominence: his work with Rumsfeld, his tenure as Chief of Staff under Ford, his eventual time as a congressman. The film notes the strings Cheney is pulling, removing various legislative and financial protections to increase profits for the wealthy minority and to augment the power and minimize the culpability of the president (strings that will be right where he left them, decades later, for him to tug on as he needs upon his return to the White House). The second half is about Cheney’s tenure as two-term Vice President under George W. Bush, his control of governmental decision-making, his role in providing a purely conservative media outlet, and, most importantly, his manipulation of the 9/11 terrorist attack into a war as an excuse to acquire control of oil suppliers.

The film’s argument is that Cheney is the evil ventriloquist of American politics (which is a solid argument to make), with George W. Bush as a viable dummy (Sam Rockwell). I, personally, think that the movie goes too easy on Bush, though, offering him an idiot’s defense—that he was too stupid to have meaningfully participated in the destruction of American government. Which isn’t to suggest I’m going to argue that Bush is smarter in real life than in the movie, but simply that the movie is mostly so concerned with taking Cheney down it allows us to laugh at Bush’s stupidity and inexperience more than fear it. It’s not unusual to see Bush played as a confused idiot, but Vice pushes things a little further: he’s a loud, drawling, drunk, clumsy, rootin’-tootin’, cowboy-boot-wearing moron with daddy issues. He’s funny. In the scene in which he asks Cheney to be his VP, he breaks his train of thought to holler to his secretary to bring him some burnt-ended brisket. It’s a wonder they didn’t just cast Yosemite Sam.

But the film does not merely despise the actors of the Iraq War—and this is where the film really starts to sour. It very contemptuously and conspicuously slams the average American voter/consumer for being too stupid to know what’s going on in the United States—too stupid, the film articulates, to even go see this political movie Vice. I’m serious—the film practically spits at consumers of popular culture, emphasizing their apparent low brainpower, working-class exhaustion, escapist entertainment preferences, and disinterest in important political issues, and explaining that these qualities are what makes them lemmings. In one scene, which is played for laughs, a bunch of valley girls ignore a discussion of relevant contemporary politics in their own focus group to remark that they can’t wait to see the newest Fast and the Furious movie. (Because apparently enjoying pop culture is a sign of lowbrow preferences, political disinterest, and general idiocy?) McKay, perhaps now a stuffed-shirt after a career writing and directing the super popular Will Ferrell comedies Anchorman, Talladega Knights, The Other Guys, and Step Brothers, seems to have a bone to pick with people who do not take government as seriously as he does. It is a self-congratulatory move, which ballyhoos the exceptionalism of Vice’s own audience, and which turns the movie from being quite interesting into something that is also hypocritical, immature, and elitist.

The representation of Bush as a Beverly Hillbilly underscores this profound elitism. Why make Bush an almost-backwoods, barbecue-sauce-stuffed Southern boy, instead of the quiet son of a prominent East Coast (that’s New England to the Southeast) Republican dynasty? In the same manner, scenes of a fierce Lynne Cheney stumping for Dick during the congressional race feature her railing about bra-burning New York feminists to crowds of plaid-clad truckers in cowboy hats drinking cheap beer. There’s too much scapegoating and blaming of “average” Americans in a film which should mostly hold accountable the wealthy, privileged individuals who worked to rob the rest of us of our paychecks and our rights.

The film likes to emphasize all of the near misses in this story—Cheney’s several DWI arrests before he even graduated college, his five heart attacks, the infinitesimal margin by which George W. Bush beat Al Gore, the fact that by Supreme Court order the remaining votes from Florida weren’t ever actually counted, and even George W. Bush’s apparently out-of-left-field decision to invite Cheney on the Republican ticket at all. America came so close to avoiding decades of perpetual unscrupulousness. I will say that the film does highly important work reminding us just how similar the Bush administration is to the Trump administration (there are some images of Donald Trump, Mike Pence, and Jeff Sessions sprinkled into the montages, aside from, certainly, the glaringly similar thematic overlaps between the two regimes). In the never-ending Bond villain monologue which is our current political state, it is increasingly important never to permit the Bush Administration to feel “not so bad anymore.”

So, Vice is a real mixed bag. It’s superbly condescending in presentation, but the factual morsel underlying its case is crucial. And the acting is fabulous; Christian Bale is incredibly, forensically apt at becoming Dick Cheney, while Amy Adams is an excellent Lady Macbeth (literally—there’s a Shakespearean monologue thrown in). Tyler Perry makes a nice cameo as a remorseful Colin Powell. And Steve Carrell is great as an off-the-wall, old-guard Republican Mephistopheles. But the film, on the whole, sees itself too much as having to educate its audiences rather than simply present an argument, so much so that its own entertainment value plummets. It’s nice that it wants to condemn Cheney, but it’s Cheney-esque itself in its methodology. Who wants to see a movie that believes itself to be superior to the capacities of the general audience? As McKay’s screenwriter William Shakespeare once wrote, “virtue itself turns vice, being misapplied.”