Images ©2023 by Samia Pendleton, courtesy of French Institute/Alliance Française

A review of “dSimon” by Simon Senn & Tammara Leites

October 6-7, 2023. FI/AF Tinker Auditorium, New York City

By Nikita Shepard

Why does artificial intelligence seem so unsettling? The answer we give to this reveals more about the cultural anxieties of our era than about the technology itself, as exemplified by shifting artistic responses to AI over the decades. The terror posed by the sentient supercomputer HAL that killed its human crew in the 1968 classic 2001: A Space Odyssey spoke to fears of nuclear war, as technologies appeared to pose an existential threat to the very beings that created them. In the coldly materialistic 1980s, the cruelty shown by humans towards robots in Blade Runner spoke to concerns about the decay of humanistic values in a high-tech society.

While these classics critiqued their societies using AI themes within conventional genres, most often films or novels, the wide accessibility of interactive AI tools today has enabled wide-ranging experiments with form. Ironically, however, as these technologies become not only objects of speculation or plot devices but technical components within new creative works, many artists today are deploying them to gesture back towards older tropes. Well over a century ago, fears over the evil impulses that lay beneath the surface of the civilized personality animated novelists from Robert Louis Stevenson to Joseph Conrad and helped to spark the Freudian revolution that brought terms such as “the unconscious” into everyday parlance. Today, AI tools such as ChatGPT, by virtue of being trained on massive data sets comprised of human creative output, are often interpreted as technological projections of our society’s collective unconscious, and contemporary artists who engage such new technologies draw on this perception to add a charge to the uneasy ambivalence of the public’s perceptions of AI.

dSimon, a performance by Simon Senn and Tammara Leites, promised to fall squarely into this genre. After debuting in 2021 in Switzerland, the piece recently appeared in New York as part of the French Institute/Alliance Française’s Crossing the Line Festival. The premise is simple enough: Senn, a Swiss visual and performance artist interested in questions of digital life and identity, collaborates with Leites, an Uruguayan-born programmer based in Geneva, to create “dSimon,” a virtual avatar. Senn provides his personal data, Leites uses it to program an AI that will generate text in response to prompts, and the team tracks how it unfolds over time. They use it to generate material for performances and interact with audiences, create digital visual simulations and voice actors to enact them, bring it into virtual conversation with video-generated projections of Elon Musk, and reflect on the purportedly unexpected directions its text generation goes.

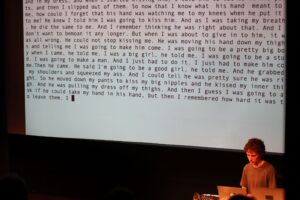

The “performance” at the FI/AF’s Tinker Auditorium felt more like a presentation, conducted primarily on a darkened stage with Senn standing behind a table with a laptop and cables and Leites projected on a screen via Zoom. Each brings images and slides onto another central screen, their mostly formulaic delivery punctuated by fleeting moments of bodily engagement. We see only Leites’ head, though her smile is warm and her speech animated. Senn’s affect is quiet, easygoing, almost shy, gazing out at the audience with a slight smile. But is it a trap?

Image ©2023 by Samia Pendleton, courtesy of French Institute/Alliance Française

The performance’s promotional text has primed the audience for the familiar affective range of intimate AI dystopia, describing their experiment as “controversial,” “intriguing,” “unsettling,” “strange,” and “disturbing.” Leites, the cheerful technician, describes tweaking the data sets fed into dSimon over time to try to hedge against some of its more noxious manifestations, as the AI spirals into a tragically predictable pattern of spitting out trollish invective. The storyline is familiar from countless dystopian plots and indignant journalistic accounts. But any deeper interest we might feel in the actual performance, the moment of our bodies together in the room, hinges on the tension produced by pushing the audience to wonder if our mild-mannered artist might have a latent capacity for cruelty, lies, racism, improper sexual desires, and so forth.

We are offered ample evidence to consider. A first clue: Leites mentions in passing in her introduction that she decided to collaborate with Senn based in part on a shared interest in, among other themes, “voyeurism.” This will turn out to be a critical dynamic within the piece—the problematic desire to look, not just by the audience, but above all by the performers. A second clue surfaces as Senn describes preparing for Leites to import his emails and personal messages into dSimon’s training data. In the same calm, flat delivery with a trace of a smile, he describes waking up in the middle of the night thinking of an email he urgently needed to delete before the AI got hold of it. We are left to speculate on the content of the email, and it is never referenced again, though it lurks in the background. The performers have established Simon as a suspect, an unreliable narrator whose hands may not be fully clean in what will come next.

Leites opens by advancing an optimistic framing of AI: its problems, she asserts, result from bad datasets, not from the technology itself, so by properly curating and gathering the right data, the technology will produce positive effects for humankind. This sort of shallow techno-optimism is easily refutable. The most basic approaches to AI ethics recognize that datasets mark only one of several possible pitfalls, in addition to discriminatory code (say, hiring algorithms that systematically privilege male applicants), inappropriate uses of data and automated decisions based on it (say, using a recidivism algorithm to deny bail rather than to increase post-release support), and oppressive social realities reproduced and amplified by technically “accurate” data and “fair” algorithms (say, predictive policing models that intensify racialized state violence in neighborhoods whose crime statistics reflect that they are already being overpoliced), to name just a few starting points. But if Leites is performing the cheerful naivete of the programmer, should we take this at face value as the underlying ethic of the performance?

To whatever extent the performers believe it, their narrative requires such a framing to dramatize the unraveling that follows. Leites and Senn invite an audience member to interact with dSimon in real time, and the AI’s responses are quirky and slightly surrealistic, teasing the spectator for ostensibly hoarding socks. But as they narrate dSimon’s evolution, they describe an increasingly disturbing set of outputs, including the production of fictional texts that describe father/daughter incest in vivid detail. The performers clutch their virtual pearls, performing dismay at dSimon’s naughty fantasies. But even as they scold their creation’s bad behavior, they project the text of this sexually explicit incest story onto the screen, scrolling down just too quickly to read in full but slowly enough to be clearly legible in glimpses. The audience churns uncomfortably in our seats. Who is responsible here? While the story itself was ostensibly written by the AI—of course, we only have Senn’s and Leites’ word for this—the performers chose to include it, chose to project it to the audience to produce the affective and aesthetic effect they desired.

![]()

Image ©2023 by Samia Pendleton, courtesy of French Institute/Alliance Française

Continuing with the gambit of the AI as a co-author of the project, Senn announces that they have asked dSimon to design an interactive performance to include the audience. The short description they read—supposedly authored, like the incest story, by dSimon—sounds like a slightly garbled copy of Stanley Milgram’s infamous experiment on obedience. In “his” proposal, two audience members (one man and one woman; dSimon is quite specific about the gender roles) are to come to the stage, strip naked, wear reflective smartphone-esque goggles obscuring their vision, and affix a system of wires to themselves whereby the woman periodically administers a painful electric shock to the man without his knowledge.

Now, Senn announces to the audience in his quiet deadpan tone, we will carry out dSimon’s performance. Who would like to volunteer? We sit in uncomfortable silence. Senn maintains the same Mona Lisa smile, allowing five, ten, twenty seconds to pass, while Leites stares grinning through the Zoom screen. Again, a protracted moment of sadism directed at the audience, with the same projection of responsibility onto the misbehaving AI. But the pleasure on Senn’s face as he stares out at the audience’s discomfort undercuts the supposed distancing. When no one volunteers, they produce a video clip of a version of the performance they previously filmed; two naked artists stumble around in goggles in a derelict warehouse, one periodically lamenting the pain of electric shocks inflicted through a wire attached to his leg. Again, the lesson is ambiguous: even if dSimon produced this “performance,” Senn and Leites chose to include it, to stage and project it, to prolong its moments of discomfort, to affirm its cruelty and inflict it on the participants and spectators. Again, who is responsible here?

The ethical valence of this scene depends on the audience seeing our Simon as a reliable narrator—the superego relative to his/our society’s AI id, the teller of truth against dSimon’s digital fake news, and so forth. But we’ve already been given evidence to be suspicious of this. The most interesting thing to consider isn’t whether Simon, who performs being disturbed by dSimon’s incest narratives, secretly or subconsciously harbors dark fantasies that are revealed by AI projections. (What was that email he awoke in the night to urgently delete?) It’s more interesting to consider why Senn consciously finds it artistically pleasurable to literally project those incest fantasies onto an audience, while displacing responsibility for them onto an AI.

This exemplifies what I call “the AI alibi.” Programmers and users of data-driven technologies increasingly deploy them as projection screens for all manner of bad behavior, from the low-grade sadism of the performers in dSimon to the racist policing and adjudicating enabled by predictive policing and recidivism algorithms. Yet in doing so, they displace responsibility for the oppressive social realities they input and the harmful consequences they output.

dSimon exemplifies and performs the AI alibi. In effect, the artists create two characters: Simon Jekyll and dSimon Hyde. This familiar trope of the morally bifurcated doubled self, stretching back to Stevenson and Wilde’s Dorian Grey, intersects with the long arc of cultural anxieties over technological creations overcoming their creators from Shelley’s Frankenstein to Kubrick’s HAL to Black Mirror. The Freudian reading is not just obvious—it’s too obvious, overdetermined. If dSimon is just an extension of Senn himself, a projection of his datafied life remixed through the idiom of ChatGPT’s lexical rules, AI appears as nothing more than a technology for externalizing the subconscious, a window into or mirror of the problematic chaos of the id—whether of an individual or of a whole society. The project of AI reform then becomes nothing more than a high-tech reboot of the struggle of the superego for control over the id: the triumph of self-discipline, gender socialization, sexual adjustment, and sublimation, assisted by the firm but loving hand of the trained professional.

This narrative arc of AI redemption unfolds in distinctly gendered terms over the course of dSimon. As noted above, when the dSimon Hyde concocts an incest fantasy or designs a performance involving a naked woman torturing a naked man, Simon Jekyll consistently describes it as “he”; given that “his” bad behavior seems to cleave to suspiciously gendered patterns, the pronoun usage reinforces the permeability between IRL Simon and dSimon and the implication that such behaviors reflect a projection of the male artist’s subconscious. Towards the end of the performance, however, as Simon relates how when he described his emotional struggles to the AI during the pandemic, dSimon suggests that he relax by booking a session in a sensory deprivation tank. (The targeted ad for the business appears in his social media feed two days later.) This turns out to be unexpectedly well suited to soothing his distress, which unsettles him. “It’s disturbing,” he reports, that “the AI knew exactly what I needed.”

dSimon has been described entirely with male pronouns up to this point; suddenly, when it is framed as providing care in a way that leaves Senn feeling vulnerable, the masculine gendering evaporates. Was it more disturbing to Senn that an artificial intelligence accurately and caringly gauged his needs, or that a masculine intelligence did? The projected gender-congruent other/self, the digital Narcissus, can comfortably be a servant, a co-worker, or even a master, but proves queerly disturbing as a caretaker. The heteropatriarchal algorithm structuring the grammar of gender operates perhaps even more strongly on IRL Simon than on his digital avatar.

This gendered dynamic reaches its apotheosis at the performance’s conclusion. Leites offers a closing monologue reflecting on the project, speaks briefly to dSimon in Spanish to prompt a response, and on the projector screen, a final message flashes: “Yo te quiero mucho.” Leites beams, the audience coos, cue applause. dSimon’s “response” (if that’s what it was) to Leites’ prompting with a message of love restores our sense of the proper gendered order and our techno-optimism. The uncomfortably homoerotic or gender-transgressive implications of a masculine-gendered AI caring for Senn are sidestepped; through engagement with Leites’s feminine warmth, the AI has learned to respond in an appropriate way. The trollish incel provocateur AI has been domesticated by the lover/mother/programmer, and we can all breathe a sigh of relief.

Image ©2023 by Samia Pendleton, courtesy of French Institute/Alliance Française

![]()

Reading the gender politics of dSimon illuminates just one of numerous ways that the AI alibi operates to naturalize existing social power relations under the guise of critical engagements with emerging technologies. The performance exemplifies the turn away from structure to psychology in dramatizing and diagnosing the pathology of AI, as the attribution of responsibility to a “bad dataset” implies liberal politics of representation as an ostensible corrective. At one point, Leites didactically recites statistics on the reported race, sexual orientation, and dis/ability status of the creators of the training data used at one stage in the programming, implying that tweaking these demographic inputs will produce a more just dSimon; the piece drives this conclusion home when the input from a woman of color speaking in a different language, by the magic of an intersectional politics of data representation, induces an appropriate loving response. If the problem is the dataset, we have to become better people, or, failing that, will need better curators of the problematic data we generate.

But this framing misses the point of the actual operation and stakes of AI today. The real problems generated by big data-driven technologies stem from the concentration of power in the hands of tech corporations, programmers, and the governments with which they collaborate, and the deployment of that power towards the end of profit above all else. That’s true whatever dataset we feed into the algorithms. Today’s data barons, no less than the oil barons of the nineteenth century, consolidate their power through controlling the era’s key raw material for economic development. And like the magnates before them, the Zuckerbergs and Bezoses of today frame this as an inevitable step on the path to progress and human improvement, refusing to acknowledge the political disempowerment or environmental costs that result. Today’s AI apologists, like the novelists and Freudians whose ideas emerged alongside the rise of the Rockefellers, train our attention on the threat posed to civilized life by instinctual drives beneath the surface of our awareness, away from the structural conditions that immiserate the majority and incentivize competition and cruelty.

Perhaps this is not the only AI we could have. But it is the one we have currently. Today, technological development accelerates according to the dictates of profit within a matrix of racial capitalism and mass surveillance, while a withered, fractious gerontocracy shrilly asserts a flimsy regulatory power in the name of an illusory democracy. In this context, we are unlikely to find ourselves with a regime of AI oriented towards human and ecological flourishing without much broader revolutionary changes in the society that produces it.

Insofar as artists today use artificial intelligence to reify the AI alibi, they draw on the lingering power of psychoanalytic tropes to direct us towards liberal “solutions” that validate the escalating securitization of contemporary life. We need a post-Freudian AI politics that brackets the focus on the unconscious—dethroning the programmer (and the artist) as psychoanalyst—and envisions collective resistance to the all-too-conscious structures that concentrate digital power. Refuting the AI alibi will mean holding everyone who engages these technologies—developers and programmers, governments and corporations, performers and audiences—accountable for the oppressive effects they produce and amplify.