Since its release on Netflix in October, Chilling Adventures of Sabrina has frequently been discussed in terms of its politics. The series, a macabre reimagining of the saga about the chipper teenage witch (based on Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa’s updated comic of the same name), is an extended allegory about female power and patriarchal oppression. In its handling of these concepts, it’s about as subtle as Halloween. But while the show is preoccupied with exposing sexism in power structures, it also slowly reveals and condemns the group of women who allow, enable, and defend such institutions of tyrannical misogyny.

The half-witch Sabrina Spellman (Kiernan Shipka) and the full-witch aunts who have raised her, Hilda and Zelda (Lucy Davis and Miranda Otto), are part of a coven of witches who derive magical powers from a Satanic contract. The show begins shortly before Sabrina’s sixteenth birthday on October 31st, when she is expected to celebrate a Dark Baptism, a ceremony in which she will make a deal with the devil, exchanging her soul for full use of her powers, proper training in sorcery, and enduring youth and beauty. But Sabrina, who does not want to abandon her mortal life or clueless boyfriend Harvey (Ross Lynch), has some reservations about exchanging her freedom for augmented power—mostly because she’s suspicious of Satan’s treatment of this power as a reward. He clearly expects that recipients of magical abilities will permit his total dominion over them, including that they (at least the women) stay virgins until their baptisms. “Why does he” Sabrina asks her aunts, clearly articulating the show’s propelling interrogation, “get to decide what I do or don’t do with my body?”

Satan is, in Sabrina, the ultimate sinister patriarch—jealous, possessive, and insistent on the inferiority, objectification, and devotion of women, while desperately relying on and obsessing over their labor, loyalty, and bodies (Jessica Goldstein has suggested that this Lucifer is the “original incel”). But the Devil is also a backgrounded figure—we occasionally see him as a CGI Baphomet, but much of his onscreen work is carried out by others. One proxy is the grim dark-priest Faustus Blackwood (Richard Coyle), whose personality is just as terrible as his name. Considering, though, that most of the characters (including the plucky, perky protagonist) worship a power that would render them the monsters or villains of most horror movies, Sabrina instantly winds up redrawing expected lines of good and evil in its particular genre. Evil in Sabrina is incarnate in those who refuse to allow Sabrina the right to choose what to do with her body and soul. Sabrina, first and foremost, upholds consent as a fundamental right.

The villains of Sabrina, therefore, are those who plot to take away her choices, like Blackwood, who plainly lies to Sabrina about the free will she would have if she trades in her soul. And the show features many condescending jerks—including Sabrina’s high school principal George Hawthorne (Bronson Pinchot), who articulates such chauvinistic and discriminatory drivel that it’s not dissonant when Satan possesses his body to briefly yell at Sabrina. But these loathsome men are not the primary villains; the show’s true, clear antagonist is a woman.

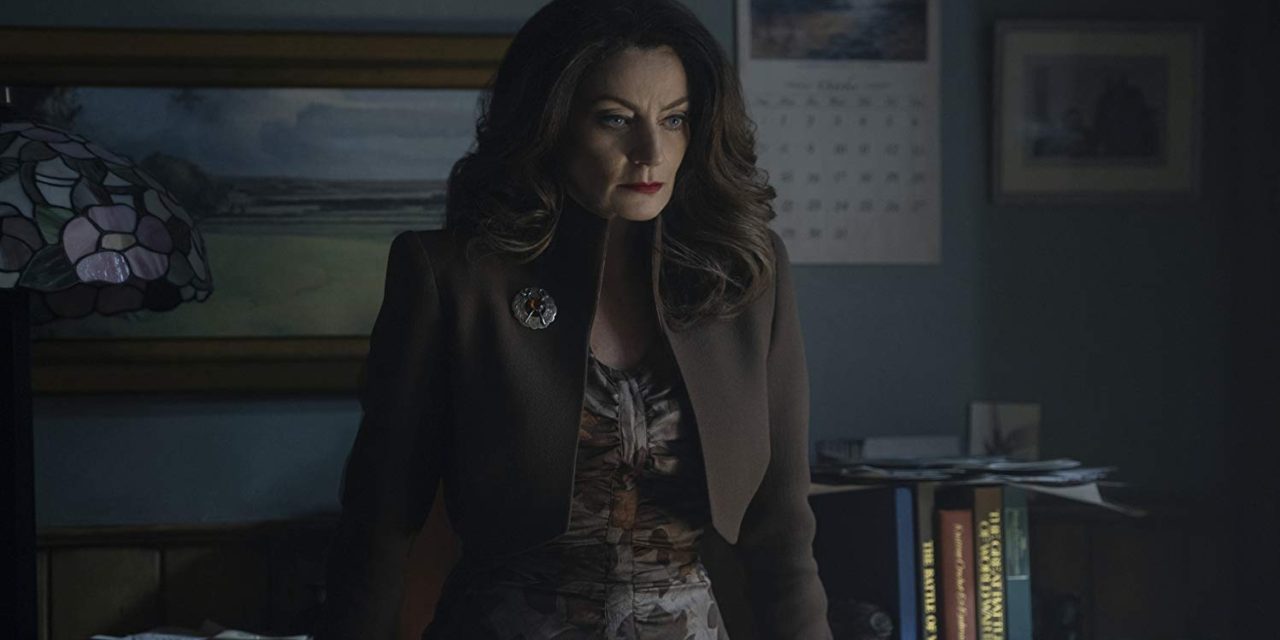

Her name is “Madame Satan” (Michelle Gomez, whose face is a carnival of sardonicism), and she has taken over the body of Sabrina’s teacher, the awkward, ironically-named Ms. Wardwell. Madame Satan, the show’s most willing, invested Satanic messenger, is body-snatching so she can manipulate Sabrina towards the Path of Night, after which she plans to rule hell as Satan’s companion. The derivative, feminized nature of her chosen title says all you need to know about her internalization of gender-based hierarchy.

Sabrina, then, represents the ways in which women support, enable, and glorify patriarchal institutions that expressly rob all women (and other marginalized groups) of rights. The show is full of women, allied with this system, who are fine with their subordination. Aunt Zelda, for example, is pathologically devoted to the men who run her religion, and is incensed by Sabrina’s uncertainty towards joining it. In Episode Seven, which details the preparations for a holiday known as the Feast of Feasts, Sabrina is horrified to learn that the event’s main dish is the sacrificed body of an elected witch, and that this is an honor most coven members would, well, die for (Zelda throws her name into the hat). This is the show’s most literal breakdown of misogyny: the simultaneous fetishization, control, and destruction of the female body. It’s fairly hyperbolic, but it does kick the show’s methodology over to satire, at least for a heartbeat; as Jonathan Swift has taught us, there is no better way to blazon systemic inequality than by representing the powerful devouring the bodies of the inferior.

In order for the patriarchy to work, though, women must be convinced that this is what they deserve, or at least that they will benefit from it. The wisest thing about Sabrina, then, is that it does not delineate the patriarchy as the order of men—it is the desires of (privileged, white) men willingly fulfilled in part by many (privileged, white) women.

Exit polls from the 2016 election revealed that 53% of white women voted for Donald Trump—Donald Trump, whose longstanding anti-women agenda could not have been made clearer. In the Alabama Special Election in 2017, 63% of white women voted for Roy Moore, the known sex-offender and targeter of teenage girls. In the 2018 Georgia governor’s race, 75% of white women voted for Brian Kemp, the Republican anti-abortion candidate, over Stacey Abrams, a firm defender of women’s rights. And 59% of white women voted for Ted Cruz in the Texas senatorial race, while only 39% voted for Beto O’Rourke.

All women know some sort of patriarchal oppression, but white women rarely, en masse, support candidates who can help them escape theirs, let alone help others do the same. In fact, it is primarily when they can help to squash the rights of other women and minorities that white women seem to fully mobilize. In an interview with Vogue, Elizabeth Gillespie McRae, the author of Mothers of Massive Resistance: White Women and the Politics of White Supremacy, pointed out “white women’s historic role in upholding racial segregation, from campaigning against the United Nations (on the grounds that it would upend the racial divide) to rallying against school integration after Brown v. Board of Education.” And guess what? “The Confederate monuments that have caused so much modern-day controversy… were often funded by white women’s organizations, prior to the 19th Amendment.”

Such actions are the results of a white-focused patriarchy that particularly rewards the obedience of privileged white women with more privilege. Prudence Night (Tati Gabrielle), a witch with whom Sabrina will forge a conflicted friendship, explains that the Dark Lord certainly does take away freedom, but that it is an “even exchange” for power. (That Prudence is the show’s only complex black witch character complicates this dynamic; not only because, statistically speaking in real life, black women are monumental supporters of progressive, anti-patriarchal candidates, but also because Prudence does not seem written to be a black woman and the show misses several opportunities to meaningfully construe her power or productively represent her.) But upholding a regime that forbids women from having both freedom and power, as Prudence explicitly mentions it does, is damaging to the larger world—such patriarchies encourage select women to choose the guarantee of exceptional personal power over the insistence on widespread liberties, obviously stalling the achievement of popular sovereignty, but also attempting to penalize women who do not serve these white men.

The staunch, worshipful Aunt Zelda is the show’s embodiment of the white woman Trump voter—offering obedience and adulation to the powerful man who ensures her lifestyle. (Her unwavering devotion and defenses even in light of his extreme vileness calls to mind the Trump supporter who volunteered she wouldn’t care if Trump “sprouted a third dick” onstage.) But Madame Satan (in the body of Ms. Wardwell, who is white) offers a reading of the white female Trump administration member—right down to her sham promises of progressivism. In Episode One, she becomes moderator of the new club started by Sabrina and her friends Roz (Jaz Sinclair) and Suzie (Lachlan Watson). The group, called the Women’s Intersectional Cultural and Creative Association (WICCA), is intended to be a safe space marginalized peers. When Sabrina speaks to her about how her friend Suzie, who is queer, does not feel safe from harassment at Baxter High, Madame Satan asks if this is because of the school’s culture of “puritanical masculinity?” She drawls that “Principle Hawthorne,” who has dismissed Suzie’s situation, “is the most intolerant, the most buffoonish, the most misogynist of all,” and asks conspiratorially, “When will the world learn? Women should be in charge of everything.”

This sounds like support (woo hoo, ladies!), but it’s an edifying bit of burlesque. Madame Satan is applying the oft-used spurious definition of feminism here (gender superiority rather than equality) and her exaggerated pro-woman stance distracts from the essential critical distinction between belief in female power and support of women’s rights to equality and autonomy. After all, what good is an all-women regime if it services patriarchal ideals? Her sentiment aspires to camaraderie, but belies her indifference towards Sabrina’s real concerns, which are not about gender-based authority, but gender-based oppression and body-policing.

Madame Satan is the spin-doctor for and agent of this sinister misogynistic institution, and is using such words to try to trick Sabrina into signing away her consent (likely in exchange for greater power in Satan’s political regime), and her words rattle disjointedly out of her mouth as a string of relevant buzzwords that are so meaninglessly on-the-nose they might have come from Ivanka Trump’s book Women Who Work, a narrative full of feminist catchphrases and pretensions of sisterhood that professes to support female labor while truly dismissing it in any other variety. Like Ivanka, Madame Satan needs the cloak of feminism in order to undermine it. Michelle Gomez perfectly executes this kind of shallowness, locking her huge eyes fiercely on Sabrina as she slowly paces the room; her assertions are hypnotic, not substantive. In another scene, she eavesdrops on Sabrina and her friends as they criticize Baxter High’s tyrannical policies. As she mulls over how to use their intersectional concerns against them, the camera slowly zooms, framing her in front of a paper doll chain (cutouts in dresses holding hands limply) hanging from a window—a neat symbol of the thin, wispy illusion of feminism she epitomizes.

Much of the Trump administration’s anti-women policies involve the regulation of female bodies—expecting women to exist as caretakers, not equal workers who can choose their sphere of labor. Trump has reinstated the Global Gag Rule (which prevents the government from offering funds to organizations offering family-planning services), and rolled back Obama-era protections on working women (including that employers provide contraceptive coverage, and that companies shrink gender-based pay gaps), and has repealed funding to the United Nations Populations Fund (UNFPA), which offers women’s-health treatment to 150 countries. This attitude towards women fits the horror genre so well; notwithstanding horror’s reliance on the objectification and symbolism of the female body, cinema’s demons pretty regularly seek out (or force) women to nurture and serve them. The Omen, for example, involves the sending of an evil nanny to raise the hellbaby Damien. Other horror movies, like Rosemary’s Baby, insist on subjecting a woman to motherhood, making her bear the Satanic infant she does not want. The demon in The Exorcist picks for its host a female child—evincing that the destiny for little girls is to become chalices for other lives. Sabrina’s key conflict (between an autonomous woman and the male power that wants her to support it) is an extension of a tradition which desires women to be mothers and not sisters.

Indeed, Blackwood’s own pregnant wife, who dies while giving birth to their twins, is generally regarded as nothing more than a plot device—but in this, she is the precise embodiment of the patriarchy’s expectation of women. She is also black, and the ease with which a powerful white man disregards and disposes of her destroyed body reflects the racism that often accompanies misogyny in an ideology of white male rule, and stresses the stronger dismissals faced by women of color, and especially black women, in such a regime. Even Sabrina, exploited as she is by the men of the Church of Night, does not seem spurned by it so personally and erratically as Prudence, the secret, out-of-wedlock child of Father Blackwood he is pressured into recognizing after treating like his minion.

Madame Satan’s women-forward sugarcoating echoes the counterintuitive collaboration between the Trump administration and many women, including Sarah Huckabee Sanders, or Kellyanne Conway, or even the young White House intern whom Jim Acosta did not hit. These women have achieved significant political prestige and economic power. But their successes are built on, and ensure, the sufferings of (at least) other women. Shortly after Christine Blasey Ford released a statement explaining that the then-nominee to the Supreme Court, Brett Kavanagh, sexually assaulted her in high school, Conway (part of the administration attempting to shove Kavanaugh’s confirmation through the Senate) mentioned that she, too, had been sexually assaulted. She admitted that she feels “very empathetic… for victims of sexual assault and sexual harassment and rape.” Good. But Conway’s admittances, while supporting (or perhaps to lend sympathy to) an administration which has participated in the degradation, dismissal, and disrespect of women in general and sexual assault survivors in particular reveals, if nothing else, that empathizing with the pain of others is not enough to care about preventing future harm. This is wrong; as Audre Lorde has written, “it is the responsibility of the oppressed to teach the oppressors their mistakes.” But also, Conway’s assertion that she cares about women and victims trickily dismisses the accusation against Kavanaugh and insists that the Trump administration cares about women. As Madame Satan’s mentorship of Sabrina duplicitously offers, why would a woman who says she cares about women support a candidate who is clearly so dangerous to women? The pretense of caring about other women is necessary in the move to undermine them.

But, as Sabrina points out, for privileged white women to fight back against the patriarchy requires some serious deprogramming. In Episode Three, Sabrina’s Aunts have been suspended from their magical faculties because Satan is enraged that Sabrina is withholding her soul (which is her right). As part of this punishment, their long-lasting youth vanishes. Blackwood (a guy who cheats on his pregnant wife because she won’t put out, while complaining that the Dark Lord would not want that for him) age-shames Zelda to convince her that Sabrina needs to try to win back Satan’s favor. “Already,” he murmurs to Zelda, disappointingly, “I see the ravages of age upon you.” Zelda, the domestic counterpart to Madame Satan (not wanting political power, but social standing), longs for male favor. The Church of Night is run by men who position women as existing for their benefit and pleasure, and will therefore decorate ideal women with attention, affirmation, and power. Zelda, a powerful white woman, is stuck so far up the creek of patriarchal perception that she fully hallucinates her worth as being tied to male opinion.

It’s obsession with men that causes so much of the female antagonism that Sabrina deals with. Sabrina’s not cruising to fight other women (just the opposite—she wants to challenge the Dark Lord so she can retain autonomy while still developing her powers), but they keep clashing anyway. Episode Five, for example, follows the antics of a female sleep-demon who wants to settle a score with Sabrina’s dead father and wreaks grisly nightmares on the whole Spellman family. And the entire series is peppered with various bullying attempts (including some serious hazing) by the Weird Sisters, a trio of witch orphans who are the “mean girls” providing the show’s quotient of high-school problems, and are jealous of the Dark Lord’s preoccupation with Sabrina.

Prudence, the clique’s leader, is a work in progress—maybe she’s starting to doubt the charisma of an institution that insists on female belittlement. Her slowly budding friendship with Sabrina allows for various redemptions (including scaring some jocks who assault Suzie). Indeed, many moments of female conflict in the show give rise to glorious female collaboration; Madame Satan, Sabrina, and her two aunts all wind up unprecedentedly co-exorcising a (male) demon—so, damn, look at what they can accomplish if they all work together. But Madame Satan also does many things that look like female solidarity but turn out to be self-serving. She rescues Sabrina’s family from the sleep demon, but it’s because she can’t have them trapped in nightmares when she needs to tamper with Sabrina’s will. And Madame Satan encourages the exorcism precisely to demonstrate Sabrina’s impressive powers to Satan.

Chilling Adventures of Sabrina refuses to allow women to be dismissed, but at the same time it asks to hold many of them accountable. It confidently reveals women (among them, the white and privileged) as holding up an evil order that does not actually care about their kind at all. And this dynamic, suggests the show, is what it actually means to be in hell.