Michelle Chihara

When I was an undergraduate, Bob Woodward visited my upper-level nonfiction writing seminar. As a favor to my instructor, he would answer our prepared questions and give a brief craft talk. We knew that he was an alum, that he had an informal standing agreement to hire the editor of the Yale Daily News, every year, to be his research assistant. We were there to try and impress the great man in service of our careers.

The Internet tells me that as an undergraduate at Yale, Woodward was a member of Book & Snake, the Yale secret society. I heard these rumors in college, but to me they represented a world I did not understand, a world I wasn’t sure was real for most of my time in college. I wanted them not to be real, the vectors of intergenerational power that followed rules no one would teach me. Woodward was from that Yale.[1]

After his role in bringing down the Nixon presidency, during Watergate, Woodward went on to become a storied editor at The Washington Post, and then a prolific author of books about power. He has covered fully 20% of all US presidents, plus the Supreme Court.

At the time when I met him, I knew that I wanted to be a writer and a journalist, but I also had refused to write for the Yale Daily News, because in my first year someone had told me that you couldn’t work as an editor at the YDN if you had another job. Journalism at the Ivy League / Post level was very clearly structured to promote occasional exceptional working-class people or people of color, and also clearly structured to fill the pipeline with people who did not have to work during the school year or during summers. I found it classist, and took a principled stance against writing for the Daily News. No one, of course, gave a shit. For the most part, when I met Woodward, I thought it was too late for me to amount to much.

Woodward was asked a question about the CIA. I don’t remember the particulars, but the story he told in response ended with him knocking on a man’s door, uninvited, in the evening. They ended up having whiskey on the porch together, as the man revealed his secrets.

My turn to ask a question came. I scrapped my carefully pre-prepared notes and asked Woodward point blank: Could I report stories the way that he reported them? Could I do what he did?

He looked at me—a 20-year old woman, indeterminate ethnicity, maybe brown, maybe Asian, big hoop earrings and an attitude—and answered me with a gentle but flat “No…”

The next question Woodward got was about “Jimmy’s World.”

In 1981, on Woodward’s watch, a young and ambitious reporter had turned in a story about an eight-year-old heroin addict with the pseudonym Jimmy. The senior staff at the paper, including Woodward, loved the piece, and put it up for a Pulitzer, which it promptly won. The story turned out to be a fabrication. It is the only Pulitzer that has ever been returned.

The reporter who wrote the story, Janet Cooke, was new and driven and Black, so she was sent to cover the Black community. She was desperate to please the senior staff, the white men at the top of the paper’s hierarchy, and they had an intense affective reaction to Jimmy.

A more experienced Black reporter at the paper doubted Cooke’s story early on. Courtland Milloy returned to Jimmy’s ostensible neighborhood with Cooke, and he could tell that she had no knowledge of the place. She was not someone people in that community would have trusted, and she had no idea where “Jimmy” might be. Later, long after Cooke had left the Post, Milloy wrote a column about the movie Precious, about which he also had misgivings. He wrote, “Maybe there is something to the notion that when human pathology is given a black face, white people don’t have to feel so bad about their own. At least somebody’s happy.”

A young and ambitious Black reporter was sent to cover drugs, even though she had no skills or experience to cover that aspect of DC at the time. Milloy seemed to understand, in 1981 as in 2009, that powerful people in the mainstream were drawn to the spectacle — the fictional spectacle — of Black depravity.

In the late 1990s, in my nonfiction writing class, Woodward was still getting questions about why the Post had gotten the Cooke affair so wrong. He told us that the paper’s mistake had been not checking up on “Jimmy” sooner. If they had pushed to check on his well-being more quickly, they might have discovered that he didn’t exist. They didn’t think of the children.

Woodward did not mention race.

In his answers to both questions in my class, Woodward was forthright but clearly did not think it was important to consider how his subject position might affect either his reporting or the stories he chose to promote. The Cooke / “Jimmy’s World” scandal was so obviously shaped by its racial dynamics. But Woodward categorically refused the idea that his white male class privilege either affected the stories he got or structured his reaction to the stories he edited. When Woodward drank whiskey on the porch with his sources, he was convinced he could be detached objectivity incarnate.

After “Jimmy’s World,” he told the ombudsman about Cooke’s story, “This story was so well-written and tied together so well that my alarm bells simply didn’t go off.” For him, quality stories were indistinguishable from objective ones; seeming true could be equated with seeming good.

The ombudsman, in his dissection of the case, did address race, but only in an indirect rhetorical manner.[2] He wondered aloud if Cooke had been promoted because “she was handsome and black.” He wrote that it was possible, technically, that she had gotten the job at the Post because she was Black. It was possible that a penchant for liberal tolerance and diversity had influenced the Post to abandon its usual airtight meritocratic assessments of quality and objectivity in a Black woman’s favor. In other words, maybe the problem was affirmative action, but who could say?

In my class, Woodward acknowledged that some reporters, with certain lived histories and certain bodies, could not report the same stories that he could. But in his view this simply could not reflect in any way on the quality of the news at the Post. And even if Courtland Milloy’s and Mayor Marion Barry’s alarm bells had been set off by “Jimmy’s World” while Woodward was being snowed by its excellent writing—this did not reflect on Woodward. His reporting and editing were objective and meritocratic. End of story.

The release of Rage

Fast forward to 2020, and the publication of Woodward’s second book about the 45th American president, entitled Rage.[3]

The reception to this book — not the book itself but its reception — marked the end of an era. I read it here as the apotheosis of a narrative regime and its objective aesthetic, a regime that had structured journalistic objectivity for a long time. Both Trump and Woodward played a role in bringing this era to an end, and I want to be clear, I like Woodward a lot better than Trump, but they did an interesting dance together.

Trump refused to speak with Woodward for his first book, but after Fear came out, Trump seemed to feel that he had nothing to lose by speaking with Woodward and he started calling the reporter on his cell phone with some regularity. After 18 interviews, for Rage, Woodward ended up having had more access to the President than almost anyone else.

In the media blitz that his publisher arranges for all of his books, Woodward pushed two big takeaways from Rage: One was the fact that Trump had received credible information about Covid19 and tried to cover it up in a criminally negligent fashion. Two was a soundbite, Woodward’s pronouncement in his conclusion about Trump: “He’s the wrong man for the job.”

To oversimplify somewhat: on the left, the general reaction was that 45 being the wrong man for the job was old hat. The right was distracted by conspiracies about the Clintons eating babies and Covid being a hoax perpetrated by Democrats.

In a further twist, on Twitter, the President’s supporters turned around and blamed Woodward for withholding information about Covid19. A number of news outlets picked up this question, and asked Woodward whether he himself should have acted more quickly on the information he had heard.

Woodward defended himself by calling to his own long track record of authoritative journalistic objectivity. Woodward had been working to make his own claims about the President’s state of mind and decisions. An entire cohort of reporters at The Post had been simultaneously covering daily stories about the virus. Woodward found himself using his big line from the Watergate scandal to articulate his focus: “What did the president know and when did he know it?”

Who, What, Where, When — that’s the top of an inverted pyramid news story, the rock-solid structure of an American news story.

Woodward had to line up the facts about the virus, about the people who had spoken to the President, and their credibility, about what they had said and when. Woodward himself was not in an informed position to make a judgment about announcing the virus, nor was he responsible for such a decision. He believed he would have had to step outside of journalistic objectivity if he had tried to speak out, and that he could have created some real chaos in doing so.

Be that as it may, when the book dropped, Woodward faced a public already in the horrifying throes of the pandemic. On Twitter and in many news outlets, people looked back at his actions and wondered, did you do everything that you could to prevent this?

There is no unified, abstract, or objective standard from which to assess this question of journalistic ethics. When I was a journalist, at one point, the alt weekly where I worked sent me to a single seminar about ethics from a J-school professor. He basically gave us some legal background and rules of thumb, but at the end of the day, he told us, journalistic ethics is just this — you have to go to bed with yourself at night.

Journalism in America’s guiding light has long been: Get the story, be objective, full stop. Some journalists are taught fact-checking practices, all are taught to compete to get the story first. Objectivity itself is of course not a zero-sum position, it’s a set of epistemic virtues and practices. But when the public wanted to know whether Woodward had warned them, they weren’t asking whether he had been objective. They were essentially asking—the President’s manifold failures aside—whether Woodward had been able to go to sleep with himself at night.

Woodward seemed truly surprised by this. He had remained nonpartisan and fair across a series of Democratic and Republican administrations. He had never used his platform to openly criticize a president before. He had a track record of lining up the facts and letting the court of public opinion decide. When his book came out, he clearly thought people would listen. But the public no longer shared his faith in the overall importance and efficacy of mainstream objectivity. He had helped to shape and build a system of press conventions that functioned, at least in part and at their best, to hold power accountable in a democracy. And suddenly, those conventions were out the window and no one was listening.

The Trump phenomenon could not be brought down by careful and objective representations of the truth, because it fed upon— it feasted upon—the spectacular provocation of the liberal mainstream. The nonpartisan center that Woodward occupies was itself built by placing trust in US traditions and conventions, including but not limited to a commitment to objectivity and liberal tolerance. It was by flouting these traditions and conventions that Trump arrogated to himself a pugnacious version of rightwing moral courage.

Woodward told Dax Shepherd on a podcast that he got out of bed everyday saying, “What are the bastards hiding today?” This was the philosophy behind Woodward’s relentlessly detached, fact-based commitment to objectivity. He trusted that the American public would always respond to sunlight shining on the shadows.

But what if the bastards aren’t hiding anything, what if they’re letting it all hang out?

Woodward must have seemed downright quaint and friendly to Trump. Trump openly ditched the press pool, he openly displayed particular venom for women and women of color and people of color and journalists, during press conferences. He obstructed justice and then crowed about it on Twitter. His final act was to let the system’s claim to racial neutrality skewer itself on its own inability to send police to protect the capitol. The Russia-friendly felons populating the Trump Team, Maria Butina, the wild profits flowing to former staffers at “American Ethane,” [4] the cages at the border, the doctors reduced to tears in New York hospitals, the health care workers committing suicide… The public has been informed. When power garners support not by claiming fealty to an objective standard of justice and self-evident truths but by openly embracing baser interested motivations, sunlight has a different effect.

Journalistic objectivity does many things well. But it has proven incapable over the course of 19th and 20th century history of shifting widespread cultural biases, and given its relentless presentism, it does not always understand the historical contexts against which stories define themselves. The platform and the conventions that Woodward spent a lifetime building can’t discipline Trump because Trump represents a different form of power in a different context. He thus demands a different kind of story.

In the journalism business, there’s an old saying: Dog bites man, not a story. Man bites dog? Now that’s a story.

Trump didn’t act on Covid19 fast enough… but maybe it was a Democrat or China’s fault— and isn’t it a hoax?

Not a story.

The legendary Bob Woodward, the king of objective trustworthiness, may have held back the truth about Covid19 to sell more books?

Now that’s a story.

Trust in mainstream journalism itself has obviously been dwindling, from the right and from the left. The anger at the fourth estate comes in different forms, it contains many valid class critiques, and critiques around race and gender, with both the left and the right showing varying degrees of attachment to the function of an independent press in a democracy. In the postwar history of journalism, Woodward’s Watergate reporting was arguably the high-water mark of American centrist nonpartisan journalistic ethics. His surprise, after Rage, came not because audiences questioned his objective facts but because he had lost the authority to set the terms of the narrative.

The reckoning over objectivity

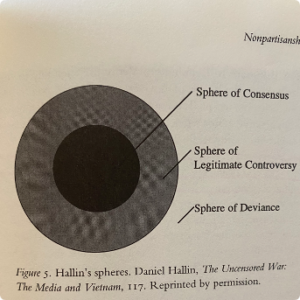

Journalistic objectivity, like scientific objectivity, was formed as a set of conventions and principles, put into practice piecemeal with evolving technologies and markets in the 19th century. As with science, it contained but was not limited to a secular reaction to religious modes of thought and institutional power. In David Mindich’s Just the Facts [5], he lists five components: detachment, nonpartisanship, the inverted pyramid — which interestingly seems to have come from both the telegraph and Lincoln’s war secretary– naive empiricism or a commitment to facticity, and balance. In 1998, Mindich recognized objectivity as the terrain where material struggles between different forms of media play out. He also chronicled the early history of journalistic objectivity as an aesthetic that meets the expectations of a centrist, white, male readership. In the 19th century, nonpartisanship in the US functioned to suppress all antislavery voices, who existed outside of the dominant party system. Legitimate political conversation did not touch abolition, which was positioned as “deviant” and beyond the realm of legitimate political conversation.

The legendary Black reporter and publisher Ida B. Wells, in the 1880s, was almost lynched herself when she had the audacity to tell the truth about lynching. The New York Times, in the name of objectivity, printed “balanced” opinions about lynch mobs while assuming the guilt of lynching victims. Black people were assumed to be rapists and brutes. Wells herself was tarred as “slanderous and nasty-minded.” She marshalled evidence that lynch mobs were motivated by economic jealousy and not by actual crimes. The Times London correspondent, in response, called for “sober-minded, responsible Americans” to repudiate her.

Contemporary critiques of journalistic objectivity on the left emerge out of this history. It is mostly Black reporters and reporters of color at the Times, in 2020, who were forcing what Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Wesley Lowery has called a “reckoning over objectivity”[6]. Lowery writes: “The views and inclinations of whiteness are accepted as the objective neutral. When black and brown reporters and editors challenge those conventions, it’s not uncommon for them to be pushed out, reprimanded or robbed of new opportunities….”

He calls for a rethinking of objectivity, without a knee-jerk inclusion of “both sides” for the sake of balance, and with a renewed commitment to truth and accuracy—even or especially in the face of cultural bias. “Instead of promising our readers that we will never, on any platform, betray a single personal bias — submitting ourselves to a life sentence of public thoughtlessness — a better pledge would be an assurance that we will devote ourselves to accuracy,” Lowery writes, “that we will diligently seek out the perspectives of those with whom we personally may be inclined to disagree and that we will be just as sure to ask hard questions of those with whom we’re inclined to agree.”

Once we step into the territory of how and where whiteness constructs the appearance of objective neutrality, we are in the territory of aesthetic criticism. How does Woodward’s objective style relate to his critical lens, and or to what another White House chronicler calls “lazy thinking” and a lack of “moral curiosity”? For Alexander Nazaryan, Woodward deserved some respect for having “deposed” Nixon and won a series of Pulitzers, but the trust extended to him had specifically aesthetic limits:

“A lack of anything remotely resembling literary ability has long been excused on the grounds that Woodward is a first-rate reporter, and first-rate reporters cannot afford the luxury of craftsmanship. The reliance on cliché is a necessity. But nobody wins when we go easy on the Bob Woodwards of this world. Lazy writing is lazy thinking, and lazy thinking is what got us into this whole mess” [7].

There’s a marketplace of ideas metaphor here, but leaving that aside, objectively speaking Woodward is not a lazy man. If his writing seems aesthetically expected, it is in the ways that it refuses to push back against base-level structures in our American context, it is in his objective aesthetic that refuses to ruffle existing cultural biases. In this, Woodward demonstrates his implicit belief that the story is enough, or that somehow the marketplace of ideas will bring about the longterm efficacy of liberal tolerance and progress. But Woodward’s objective aesthetic has not in fact made much progress on race and gender and class because it can’t quite bring race and gender and class into focus, just like it can’t do snark.

Woodward’s version of nonpartisan objectivity has long been too constrained to see the truths that make up the bigger picture—truths about the drug war, about race and mass incarceration, about the limits of both mainstream parties, and about health care and the severity of economic inequality in the US.

None of this means that objectivity should be ditched entirely as an epistemic virtue, or that the reckoning that has come for it can’t proceed. Journalism and criticism—both the production of accurate representations of recent events and a consistent practice of interrogating and re-framing how narrative representations are made, circulated, and understood—these seem obviously necessary for anything like democratic praxis. After the shootings in Atlanta, some editors told Korean journalists they couldn’t cover their own community’s experiences because they might be “too emotional”[8], and therefore not objective. I only know this because the Asian American Journalists Association organized to articulate a collective response after the tragedy. Racism is on the rise, but as an Asian American woman, I have felt heartened by the clear-eyed willingness to grapple with history and build solidarity on display in the Asian American community, from wildly varied groups [9]. Knowledge can only be created within epistemic communities that share epistemic values like accuracy and fairness. The intellectual labor of building shared contexts to support representations of truth is painstaking, as are qualitative efforts to ask why some stories strike certain audiences as more compelling than others.

Whiskey on the porch comes after.

Notes

[1] see Leigh Bardugo’s Ninth House for a phantasmagoric fiction based on Yale’s deep state

https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1981/04/19/the-players-it-wasnt-a-game/545f7157-5228-47b6-8959-fcfcfa8f08eb/

[2] https://bookshop.org/books/rage-9781982131739/9781982131739

[3] https://www.cnbc.com/2019/02/21/russian-backed-ethane-company-hires-lobbying-firm-connected-to-trump.html

[4] https://nyupress.org/9780814756140/just-the-facts/

[5] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/23/opinion/objectivity-black-journalists-coronavirus.html

[6] https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/books/story/2020-09-15/review-rage-by-bob-woodward-review

[7] https://www.aaja.org/2021/03/18/aaja-encourages-newsrooms-to-empower-aapi-journalists-and-their-expertise/

[8] From the AAJA to Asian writers and reporters, from activists online fighting for Tibetan freedom to organizations like Tsuru for Solidarity working to support reparations for African Americans — and here is Cathy Park Hong on Atlanta as a turning point

[9] https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/03/cathy-park-hong-anti-asian-racism/618310/