The film I am not making begins: David died. 3:47 am EDT, May 1, 2020, Queens, New York.

Why document anything—an event, a moment, a person, a place? Memory being what it is, fragile and deceptive, relics help to stabilize these fleeting images but each quickly becomes another relic, almost as fleeting as the first. Memorializing the past, remembering the past, revisiting the past—a past that will have already evaporated at the moment of its technological recording as image, as sound, even now with instantaneous digital recording—always occurs under pressure: a way to ward off forgetting, historical obliteration, death.

This is what Roland Barthes teaches in Camera Lucida, a book written in the wake of his mother’s death, a book that relentlessly turns its regard backward to recognize how the images of and from the past recalibrate the lived now, and with it, those living now. Documentary, at once a refutation and deep acknowledgment of death, serves as a memento mori. Why else the fascination with archival images—old newsreel footage, photographs retrieved from a family album, haunting street scenes from an earlier time? Why else the desire to hear the shouts and murmurs of voices speaking out against tyranny or muffled in fear of discovery? Whether moving or still, silent or capturing recorded sound uttered at the moment or recalled later, synced up or not, the document testifies to presence…even a presence that cannot be seen. Especially a presence that cannot be seen. Fiction intrudes. The question of why slides into another: how to document anything?

For Barthes, that lighted room of memory curled within the still image can only be approached through language. Withholding the photograph of his mother that apparently triggers his flood of memories, his writing to and for us the readers, diverts the original document. Access to it is blocked yet fulfilled by words. Parenthetically. He explains, emphasizing by bracketing the thought: “(I cannot reproduce the Winter Garden Photograph. It exists only for me. For you…at most it would interest your studium: period, clothes, photogeny; but in it, for you no wound.) His wound, his punctum, comes out of a past that precedes his past. It cannot be resurrected by or for another.

Speaking of her desire to film during her trip through Poland, Russia and the other Eastern European lands emerging into view after the fall of the Soviet system, after its demise, its death, you might say, Chantal Akerman called her mode of working “my own style of documentary bordering on fiction.” A desire seen in D’Est “to shoot everything. Everything that moves me.” Everything is qualified, though; everything that moves her, which, like Barthes’s photograph of his mother, is private, hidden, apart from what might move you or me.

In his film, Tracking Edith (2016), about his great aunt, the documentary photographer Edith Tudor-Hart, Peter Stephan Jungk incorporates animation as a means to fill in the numerous gaps in her life, a life purposely lived invisibly, leaving few traces. Edith Tudor-Hart died in obscure poverty in Brighton, England, in 1973, a sad final chapter in a complex life lived across Europe’s nations and history. During the 1920s, she had trained as a kindergarten teacher under Maria Montessori, studied photography at the Bauhaus, and in the 1930s, notoriously helped recruit Kim Philby and the Cambridge 5 as spies for the Soviet Union. Despite her reputation as a socially committed photographer in the 1930s, her death barely registered; she ran a small antiques shop when Tudor-Hart died alone of cancer, her grave essentially unmarked.

So, like Akerman’s quest in D’Est (“Why make this trip to Eastern Europe?” she asks, answering herself: “There are obvious historical, social and political reasons…There might also be personal reasons for going.”), Jungk’s journey of remembrance is at once a personal mission—a great nephew’s effort to retrieve the memory of a family member—and an intellectual and historical act of recovery—a search through archives and records and other’ memories for details of a story almost nobody wanted to recall. Although Tudor-Hart lived at the center of many of the crucial events of the 20th century, interacting with those personalities, philosophies, movements that shaped them—communism, fascism, psychoanalysis (she’d had an affair with her son’s psychologist, Donald Winnicott, in the 1950s), radical education, documentary modernism, the Spanish Civil War (where her husband served as a physician), the British film industry (her brother is a noted cinematographer)—she nevertheless eludes. Memories of her had evaporated. There were reasons: shame, madness, treason. Even now, few want to acknowledge this disreputable past. Photographs remain. But her story required imagination to recreate. A spy’s hidden life revivified through animation—a process that literally brings stillness into motion.

What cannot be said or shown about a Stalinist past burrowed within?

To retrieve the shameful history of a state—for instance, Stalin’s show trials—all that might be needed is to uncover the original document itself: archival footage of the theatrical performance of confession and abasement by those deemed enemies of the state.

In The Trial (2018), Sergei Loznitsa reconstructs found footage of one of the first show trials staged by and for Stalin in 1930. Loznitsa’s film is made from the actual film orchestrated, in fact, directed by Stalin himself, who watched the daily rushes of the filming and choreographed the next day’s action. It reveals how the mechanisms of state power are lodged in the literal fiction of confession. Over the course of eleven days, the engineers and economists accused of sabotaging the USSR through their adherence to “The Industrial Party,” while spying for French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré, confess to elaborate conspiracies to wreck the Soviet economy by repeating rote language they must learn to the letter.

Distilling the entire event, staged for a large audience, both present in the hall and following on radios throughout the nation, Loznitsa’s two-hour documentary edits down the source material of the 11-day show trial.

The original filmed trial functioned as a lesson plan for future prosecutions. The trial, designed not to elicit the truth but to enforce a systematic approach to public confessions of guilt, determined how all subsequent trials would proceed, eliciting the expressions of treasonous guilt from those facing exile and execution for their fabricated crimes against the state, against Stalin. They must confess—and do so in the dead language they have memorized. They are already dead and they know it. Many more would follow in their path until Stalin’s death in 1953. Then, his crimes exposed, evidence, including official documentation, was culled; some of it made visible but much got expunged, purged, and so efforts at truthtelling turned into more and other falsehoods. What is the status of a falsified truth or a truthful fiction as a document, when the tellers are the disappeared?

My husband died of Covid-19 this May. He was among the first 100,000 to die in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic raging through New York City, with Queens, where I live, the epicenter of disease and death. Death has haunted me since. Now, it is “coming after all of us,” as Mike DeWine, governor of the state of Ohio, said on November 6, a few days after the presidential election resulted in Donald Trump’s defeat.

Actually, death and documentary haunt me. More than a quarter of a century ago, I published They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary, culminating decades of thought on the subject of realism, representation and political activism. Walter Benjamin, who never got to finish a book, dying by suicide en route to Spain as the Nazis closed in on his group of refugees, astutely noted in “The Writer’s Technique in Thirteen Theses”: “The work is the death mask of the idea.” The idea is death-haunted too.

On and off since 1994, I have returned to thinking about documentary through image, sound and word, recently writing on the films of Herbert Kline, Chantal Akerman, Julia Reichert, Barbara Kopple, Louis Malle and Daniel Blaufuks and the photographs of nuclear bombs. Death is behind this work: of people (Akerman’s suicide enshrouds her last film about her mother’s death, her mother dislocated by twice surviving Auschwitz; Blaufuks’s restoration of the images, real and fictional, past and present, of the dead at Theresienstadt); and of places: Reichert and Kopple making films (at least the ones I was writing about) depicting the death of American factory jobs and with them their unions and communities, Malle’s detailing the demise of God’s Country, the American Midwest; Kline’s portrait of untreated illness in a Mexican fishing village; and most terrifying, Hiroshima.

David’s presence is still palpable: I ride his bike around my neighborhood; his picture, holding a hammer aloft as he stands on a pile of rubble in the warehouse he transformed into a small experimental theater in the 1970s when we met, sits near me as I write, a painted terra cotta portrait of him at our son’s medical school graduation made by artist Judy Glantzman hangs next to a painting by my mother, dead almost ten years. I have yet to move from my side of the bed when I sleep. He invades my dreams, dreams revving through my brain as they did when I was much younger, of him and my mother being driven off in a black van by an attendant dressed in white. They are gone. Their work remains.

This work includes David Bernstein’s sole performance on screen in the extraordinary 1975 film, Milestones, directed by Robert Kramer and John Douglas. At once documentary and fiction, Milestones was restored and revived from obscurity in the United States by Icarus Films in 2006. I had heard about this film, of course from David when he reminisced about shooting his scenes; but also from former Weatherman Bill Ayers who recounted to me and David, many years later, that, while living underground following the Greenwich Village townhouse explosion, he had watched the film numerous times; not only did it feature friends and comrades and so held a nostalgic pull, but at 195 minutes, it provided cover of darkness for most of an afternoon. In early November 2020, it was shown as part of New York’s Metrograph Theater retrospective of Kramer’s work. David Fresko describes it:

“Mixing documentary and fiction with a poetic, free-associative logic, Milestones is a cross-country journey that moves from the mountains of Vermont to the sculptural landscapes of the American Southwest and back to New York City’s streets. But above all, Milestones is a film about history and how people understand themselves historically, exploring how an American past characterized by slavery, indigenous subjugation, labor suppression, and imperialist aggression persists into the present and therefore weighs upon the future.”

It screened at the Cannes Film Festival on April 30, 1975, the day the last helicopter departed the roof of the United States embassy in Saigon. The war that had dominated the lives and work of the filmmakers and those in the film was over, the US defeated, leaving millions dead in Southeast Asia.

The film’s title derives from the Hȏ Chí Minh poem, “The Milestone,” collected in his Prison Diary published in English in Hanoi, 1972. When I met David shortly after the film appeared, we discovered that we both owned a copy and we took as an epigraph for our wedding invitations one of Hȏ’s lines: ‘Let the prison door open and the real dragon will fly out,” which seemed obscure and counterintuitive to most—weren’t we getting married, thus imprisoning ourselves together?—but, for us, marriage was release, a stab at forming a new collective, forgoing the loneliness and alienation of living in demented times in a debased country. Much like the film. Milestones, a thoroughly scripted yet improvised film, documents itself: “The process of making the film was the process of getting mobilized again,” the directors wrote in Cahiers du Cinema in 1975. So, a fiction bordering on documentary.

In part about the death of 1960s movements against racism, imperialism, fascism and in support of the people of Vietnam, Newark, Wounded Knee, this film is a deeply introspective look into “how white our life was,” as it explores the loose-knit “subculture part lumpen, part declasse [sic] intellectual, part proletarianized—greatly shared by, but not limited to the cultural explosions of the 60’s,” the directors explain. It is also a film about the impact of feminism on what the filmmakers call “anti-imperialism,” as the characters struggle continuously to articulate “feelings.” Their “hopeful dreams become their opposites, a kind of grim caricature or [sic] our failures to struggle, to really grapple with the problems, to get it on….”

In staging its fictional encounters, conveyed through a style of cinéma vérité, the film interrogates its own failure within the larger failure of radical documentary, as well as “the battered politics” of 1960s activists. Each character plays some attenuated version of him/herself—Grace Paley’s character is finishing a documentary about Vietnam, for example—with the exception of the pregnant woman, Paley’s fictional daughter, whose difficult birth concludes the final long section of the film.

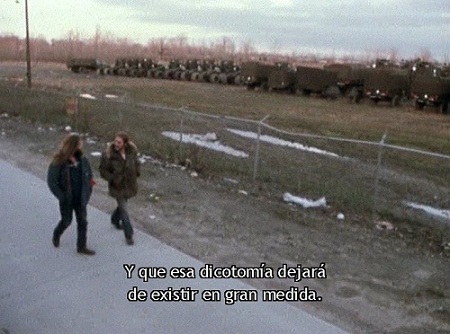

David is first glimpsed early, fixing an ancient Chevy truck for one of the main cross-country seekers, his friend Lou, and reappears a few times later when Lou, now traveling West, passes through Detroit. He’s become an autoworker organizing an insurgent takeover of the union and trying to forge multiracial coalitions on the plant floor; but his life is lonely, this loneliness made visible as the two men walk among delivery trucks serving Detroit’s Eastern Market and along rows of tanks standing like a dead army behind chain link fencing. His efforts to unite radicals with the working class seem futile, but necessary. Ad-libbing most of the dialogue, David based his made-up character on one of his friends, but he spoke his truth about dislocation and futility, not the truth; it’s fiction, but true nevertheless.

Robert Kramer and John Douglas, MILESTONES, 1975.

But there is something dangerous here—blurring fiction and truth; bringing past into present; death into life. Years ago, when I first saw the film, I couldn’t recognize David. He looked so different, skinny with long hair and his voice not his as he shed his New York accent for the role. This time his presence stabs me. He’s a minor figure in the film, you wouldn’t notice him. I do and it wounds, this cinematic punctum.

It’s chilling to watch Milestones again, now, as Donald Trump claims his defeat at the polls a fraud, as the nation clocks in over 100,000 new coronavirus cases a day with more than a quarter million deaths, as Black men continue to be killed by police…

I started writing this in early November, shortly after Trump told us not to let Covid “dominate your life.” But my life is dominated by this disease. And it is through documentary, “its concerns, its content, its form [that] are inseparable from the dialectical processes, the struggles inside this history” that death might be approached.

For documentary allows viewers, if only fleetingly, a chance to actively participate in these processes, this struggle—to find a way to live together even in the face of death….to serve as witness again…the secondary, really tertiary witness after the filmmaker and after the ones filmed. Witness to bare existence, to life, almost.

Documentary photographer and filmmaker Alice Arnold has been riding her bicycle around New York City for many years. This year, at least during the “pause” as New York’s spring lockdown was called, it was far less dangerous with cars mostly off the roads, so she could cruise the avenues at night with her camera. She forged a remarkable series of still images, “Covid Nites,” recording the garish emptiness of a city held under cover of death. Everywhere signs remind the very few people out walking dogs, delivering takeout, sorting cans and bottles from refuse that once this city thrived day and night. Now, the fluorescent lights cast eerie reflections on the sidewalks, a solitary customer peers from among the liquor bottles arrayed in the window; a walk signals to no walkers. Disease stalks everyone; but, as Arnold comments, so does “a restless energy bubbling up from the strangeness and disruptions to our everyday life activities.”

Title: The Plot Against America Busstop

Date: 25 April 2020

Location: Avenue C and 11th Street, East Village, NYC

© Alice Arnold 2020 (www.a2studio.org)

Arnold teaches documentary filmmaking at Hunter College (or she did until coronavirus destroyed higher education in the US) and I was her student a few years ago. I had met her in Prague while researching the story of André Simone in the Czech National Archives. That story is told elsewhere (see footnote 5). I had been telling her about my current project about two fathers—mine and David’s—entitled “Cold War Dads,” bemoaning that I was not sure I had the stamina to write another book and instead was considering making a film with the compelling material I had unearthed among archives and boxes stored in closets. She replied something to the effect: “You don’t have the energy for a book…well, what do you think goes into making a documentary?” She invited me to enroll in her introductory documentary filmmaking class to find out. I quickly realized that I would rather be a documentary film critic than a documentary filmmaker…and my book remains unwritten. Its narrative stalled by too many dead ends.

Just as archaeologists understand objects placed near the bones of our human ancestors to serve as funerary mementos—the stuff of life made over for death—in the Society of the Spectacle, that Guy DeBord calls the age of the image, our age, documentary collects visual and auditory detritus, marks the passing of time and thus life.

Or, in Akerman’s words, it “move[s] between the lines of the lines.”

No Home Movie (2015), Akerman’s last film about her mother, last film about herself, last film, travels across the familiar: kitchen, bedroom, living room and corridor of her mother’s Brussels apartment, where Chantal has come to care for her ill and injured mother. We know these spaces almost as well as Chantal and Natalia do from past films intensely focused on hallways and bedrooms and on their “same eyes and hair, now the same body.” The walls encase them, as does the computer screen and its camera when they speak over Skype. “Because,” as Natalia says, “we are the only ones left…I kiss you.” Mother and daughter apart, alone, together, loving in the dark and an overexposed daytime across the spaces inside a city and out on a windy plain. When her mother asks, “Are you still working on your documentary?” Chantal replies: “No, I’m in New York.” Then another question and response: Why are you filming me? I film everybody.

An effort to record a world before it is gone, knowing it is already gone, that is the work Barthes and Akerman perform: “History is hysterical: it is constituted only if we consider it, only if we look at it—and in order to look at it, we must be excluded from it.” Another’s life, another’s death. Yours and theirs…and mine. (Then again, as Barthes makes clear: “For you no wound.”. So mine and not yours.) These days, death stalks us all. But I can only speak of the death that I live with, that of the one I loved and with whom I lived for most of my life.

1 Roland Barthes, Camera Lucid: Reflections on Photograph. Trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 73.

2 This became the title of her 1995-96 installation and its catalogue: Bordering on Fiction: Chantal Akerman’s D’Est. (Minneapolis: Walker Arts Center, 1995), 17.

3 Akerman, 20.

4 One of the last show trials, the 1952 so-called Slánský Trials in Czechoslovakia, fictionalized by Costa-Gavras in The Confession (1970), was based on the memoir by Artur London, one of the few accused of “the Zionist- Imperialist plot” not executed. Among those executed, journalist André Simone, cited my father-in-law Joseph Milton Bernstein as someone who could exonerate him from illogical charges of spying in and for and against France. See Paula Rabinowitz, “My Prague Summer,” ANZASA Online https://anzasablog.wordpress.com/2018/10/29/my-prague-summer/

5 “An Incalculable Loss,” New York Times 27 May 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/05/24/us/uscoronavirus- deaths-100000.html 6 See Newsweek

6 November, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/ohio-gov-mike-dewine-says-covid-coming-afterall- us-cases-state-skyrocket-1545400

7 Walter Benjamin, “Post No Bills” in “One-Way Street,” Reflections: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings Trans. Edmund Jephcott. Ed. Peter Demetz. (New York Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. 1978), 80-81. NB: I have slightly altered the translation.

8 “It’s Still There: The Vanishing Point of Daniel Blaufuks’s AlsOb/As If,” boundary 2 47 (February 2020): 115- 144. “Documentary Can Reveal an America Hiding in Plain Sight.” Program notes and blog post for Julia Reichert: 50 Years of Film Dialogue,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, February 19, 2020. https://walkerart.org/magazine/soundboard-documentary-paula-rabinowitz “Love the Bomb: Picturing Nuclear Explosion,” in Routledge Companion to Photography Theory. Ed. Mark Durden and Jane Tormey (London: Routledge, 2020), pp. 211-227. “American Dream in God’s Country: Odysseys in Documentary, Hospitality, Place,” in ReFocus: The Films of Barbara Kopple. Ed. Jeff Jaeckle and Susan Ryan (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019), pp. 31-50. “‘I Plan to Send You Some Pictures’: Documenting the 1930s in Cold Blood,” in The Cambridge Companion to the 1930s. Ed. William Solomon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 92-110. “‘It Gets Dislocated’: The Evocative Cinema of Chantal Akerman.” Program notes and blog for “Homage to Chantal Akerman,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, October 2016. http://blogs.walkerart.org/filmvideo/2016/03/28/it-gets-dislocated-the-evocative-cinema-of-chantal-akerman/ They Must Be Represented: The Politics of Documentary (London: Verso Books, 1994).

9 Judy Glantzman, “On Obituaries and Shadows: Art in Isolation,” POP https://paintersonpaintings.com/judyglantzman- on-obituaries-and-shadows-art-in-isolation/

10 David Fresko, “Robert Kramer: Cinema/Politics/Community. Metrograph Journal https://metrograph.com/robertkramer- cinema-politics-community/

11 Hȏ Chí Minh, “Ideograms Analysed,” Prison Diary (Hanoi: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1972), 88. “The Milestone” appears on page 97.

12 Robert Kramer and John Douglas, “Milestones,” Cahier du Cinema 258-59 (July 1975): 56-61. The original in English appears in the notes to the Icarus Films DVD (November 2011) from which further quotations come.

13 Ibid.

14 Richard Eder, “‘Milestones’, a Film on Radical Youth,” New York Times (8 October 1975): 24.

15 In the epigraph to Auschwitz and After, Charlotte Delbo says of her memories of the concentration camp: “Today, I am not sure that what I wrote is true. I am certain it is truthful.” Trans. Rosette C. Lamont. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 1. I thank Jani Scandura for bringing this quotation to my attention.

16 Kramer and Douglas.

17 Personal communication, Email AA to PR (30 November 2020). The full suite of images can be seen at www.a2studio.org

18 Akerman, 35.

19 No Home Movie was shot as Akerman was also writing about the images and contexts of them. See Chantal Akerman, My Mother Laughs Trans. Daniella Shreir (Great Britain: Silver Press, 2019).

20 Barthes, 65

Politicsslashletters.org is grateful to CINEMA: JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY AND THE MOVING IMAGE for kind permission to republish.