In the wake of Bernie Sanders’ defeat in the Democratic primary there’s been considerable talk about what sort of left agenda should shape the American movement–what sort of program it should embrace, what sorts of obstacles that agenda will face on the path to electoral victory, and how long it is likely to take to convince a majority of Americans to make it their own. In this post, I want to explore the case of Spain’s upstart party Unidas Podemos, which after only six years of existence has become the junior partner in Spain’s new left coalition government. I do so both to note and explore a surprisingly pessimistic turn in the thinking of its leader, Pablo Iglesias, and to explore the parallels between his party’s struggles and those that will arise, according to two recent analyses, in any party seeking to buck the present neoliberal order.

Both Leo Panitch and Sam Gindin’s The Socialist Challenge Today (2018) and Bhaskar Sunkara’s The Socialist Manifesto (2019) call for the left to adopt a democratic socialist rather than a social democratic program. (‘Social democracy,’ as they deploy the term, designates a system in which a democratic government manages the operations and wealth of a still-capitalist economy in the interests of the people. “Democratic socialism” entails the replacement of capitalism by a more democratically structured, socially responsible, and ecologically sound mode of production.) The core of their argument against social democracy is that in it the government remains under the discipline of and can in fact be annihilated by the capitalism it seeks to manage. If capitalists feel the constraints of regulation or the drain of redistribution cutting too deeply into their profits, they need only call a “capital strike.” Then, when capital begins to flow out of government and even corporate coffers, the people suffer and social programs collapse: the social democrat’s choices are either to capitulate or to face electoral defeat. The left must make socialism its aim in order to secure the future for the vast majority.

And yet if both texts insist on pushing on directly to socialism, both are also impressively realistic, even grim, in their assessment of what this push will entail. The title of Panitch’s last interview in Jacobin, “The Long Shot of Socialism is Our Only Shot,” captures his position. The road to socialism is long and so are the odds of success. Sunkara is only somewhat less pessimistic. “Socialist transformation, he writes in The Manifesto, remains “a lofty dream, one that will take decades to come to fruition.” The authors’ frank and comprehensive delineations of the obstacles socialists will face on the road lend weight to these assessments. (Left social democracy, which they acknowledge is likely to represent a necessary stage on that road, will itself encounter many of these obstacles.) Panitch, Gindin, and Sunkara are not seeking simply to recruit followers; they recognize that activists need to have the clearest picture of what faces them in the struggle to which they are committed. This alone should make The Social Challenge Today and The Socialist Manifesto required reading for anyone concerned with the future of the American left.

But a more recent contribution to the debate should be required reading as well: Pablo Iglesias’s interview in last October’s Jacobin. Iglesias has grappled with the questions of program, path, and prospects ever since he and a few friends founded Podemos in 2014. Since then Podemos has built itself up from scratch both ideologically and as a national organization. It has struggled unsuccessfully to transmute the popular rage ignited by the Great Recession into a revolutionary electoral victory. It has faced endless challenges from within and without. And it is now facing the challenges of governance as a junior partner in Spain’s governing left coalition. Reading Challenge and the Manifesto in conjunction with Iglesias’ informal account of his party’s vicissitudes helps us see these vicissitudes in a clearer light, not as marks of extraordinary misfortune or singular folly but as inevitable to any party’s experience as it sets out to rebuild the left in our time. At the same time, reading Iglesias’ defense of his decision to abandon an anti-capitalistic posture and embrace left social democracy calls into question, at least for me, Panitch, Gindin, and Sunkara’s insistence that socialism is our only shot.

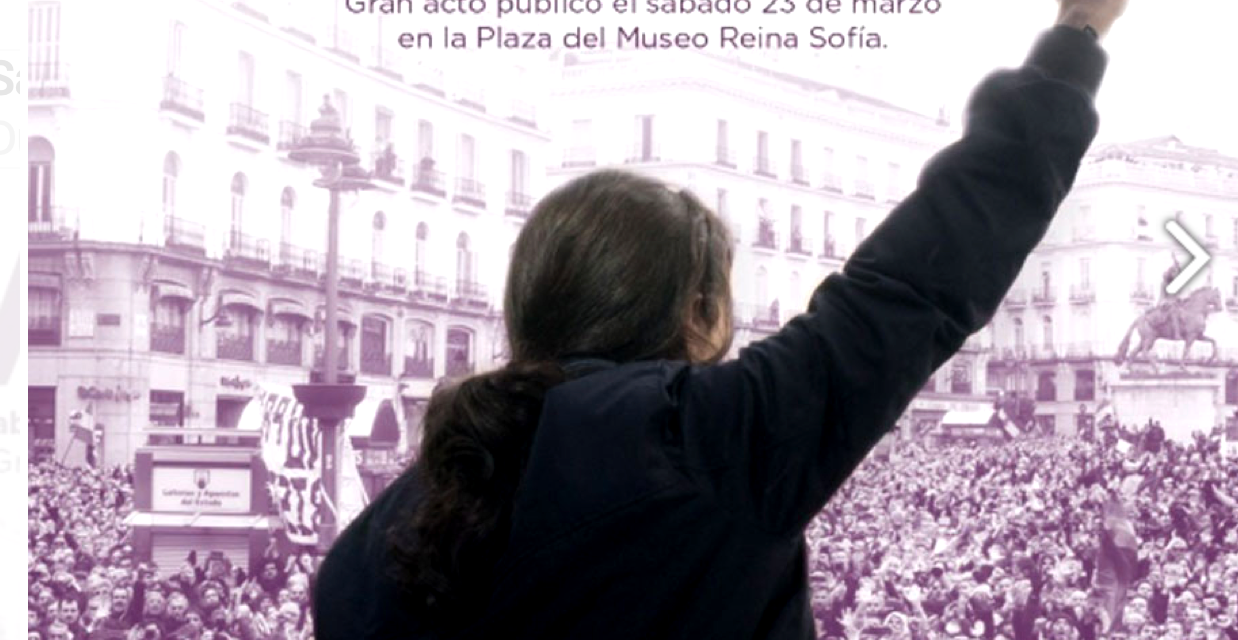

Iglesias begins the Jacobin interview on a characteristically optimistic note, announcing his intention to take a “bird’s eye view of the historical moment.” From this vantage point, he declares, he can discern “great opportunities in front of us.” In fact, this is a moment when “anything is possible.” But as the interview goes on and the interviewer bores in on the problems facing Spain, we encounter a more sober account of things. “I get the feeling that, given the current historic process, we have possibilities ahead of us — modest but interesting ones.” And when Iglesias is asked to explain his party’s decision to form a coalition with PSOE, he says something quite surprising. Already in 2018, he reveals, Podemos’ leaders knew that its early hopes of “storming heaven,”–taking power and leading Spain to a post-capitalistic future–were unfounded. “We realized,” he recalls, “that we [Podemos] would not govern for decades, even if we won the elections, because it was impossible that, given the present correlation of forces, they would allow us to govern” (italics added).

Pablo Iglesias knows more than anyone else, surely, about the situation in which Podemos finds itself today and for the foreseeable future. But his statement raises questions that aren’t adequately answered in the interview itself. Who is the “they” that have such profound veto power over Podemos’ aspirations? What other obstacles and challenges have kept it from winning enough support to govern on its own? And might addressing these challenges enable Podemos to overcome its adversaries in less time than Iglesias imagines? In other words, might today’s grim prediction be as hyperbolic, but in the opposite direction, as the hope of storming heaven that shaped Podemos’ first fiery years?

As I have said, The Socialist Challenge Today and The Socialist Manifesto courageously delineate the daunting challenges facing any effort to build a left social democratic or socialist society in the twenty-first century. Some of these challenges are intrinsic to the work of building a party to the left of today’s deeply compromised social democratic or liberal giants. This party-building entails, for instance, the creation of a large and politically well-educated cadre of party workers, the establishment of a permanent presence in tens of thousands of communities and neighborhoods, and the political education and mobilization of a widely depoliticized public. Other challenges are posed by the party’s declared adversaries, the “they” that includes the existing economic elite and its allies in politics, government, the media, and the academy. These adversaries possess great reserves of money and power. They can be counted upon to mount incessant counter campaigns designed to discredit the new party and demoralize supporters of change. And if the left takes power, they will deploy their most potent weapon, capital strike, to bring it to its knees or destroy it.

All of these challenges are already painfully familiar to Podemos. One of its chief difficulties has been in establishing a presence at the local and municipal levels across Spain. The choice to jump directly to the national and transnational (EU) level of struggle in 2014 enabled it to gain immediate visibility by fighting for recognition on its home territory, the televisual and multi-media terrain where Iglesias and his fellow founders first leapt to fame as guests on various tertulias, (political talk shows) and then initiated their own popular programs. But this strategy exacerbated a problem faced by all new parties, that of assembling cadres of organizers, tacticians, candidates, and activists to provide nationwide grassroots leadership. The “Círculo” movement—the push to build informally-structured and self-organizing local assemblies—was supposed to serve this purpose but did not, perhaps because its deliberately “horizontal” structure made decision-making and implementation cumbersome, perhaps because local circles soon found that their influence on national policy-making was very limited indeed. In any event the movement seems to have withered away, as did another innovative mechanism for building local support and ensuring input from the grassroots, the online discussion site “Plaza Podemos.” Once a host to clamorous and stimulating conversations, in recent years it has become a ghostly vacancy.

Podemos has paid heavily for this perhaps inevitable problem. It has had very little luck penetrating, as a party on the ground, whole stretches of the Spanish countryside, including Andalucia’s Serranía de Ronda, where I live 6 months a year. And even more problematically, because its founding cadres came mostly from the academic left rather than from the working classes, its presence in the vast working-class barrios of the major cities is spotty as well. This fact seems to have played a role in the much-analyzed problem of desmovilización (public abstention from electoral politics) in the large urban poor and working-class neighborhoods, which has robbed Podemos candidates of hundreds of thousands of potential votes in cities such as Madrid.

Podemos has also faced the inevitable problem of a steady barrage of well-funded and effective attacks from right-wing politicians and their allies in the judiciary and the press. Many of these attacks have turned out to be baseless; others are weakly founded on party leaders’ past work as advisors to Latin American populist regimes, media connections with Iranian broadcasters, or funding arrangements inside Spain’s byzantine university system. But still other attacks exploit weaknesses and errors within the party itself. There’s a dark complicity between the behavior of what Iglesias himself calls his inner “enfant terrible” and the successful attacks of his adversaries. This complicity was on display in his flamboyantly disrespectful treatment of the king and Pedro Sanchez, the leader of PSOE, back in 2015-16 and in his more recent purchase of a pricey chalet with pool and gardens in the Madrid suburbs. These and other cases of self-sabotage have led to months of bad press.

Iglesias complains bitterly against media harassment in the October interview, but does not acknowledge providing the tinder for his adversaries’ fires:

“They [want] to destroy us . . . knowing that there is no legal recourse [but]that if they own papers, radio stations, and TV channels, they can say for hours on end that you have a bank account in some tax haven, that North Korea, Iran, and Venezuela financed you, that your funding is illegal — all manner of things.”

“[And if the investigations they demand come to nothing] that’s fine for them, because it has allowed them, for many months already, to make sure that this is basically what gets spoken about. And afterward, they’ll invent some new scandal and there will be powerful media ready to say all manner of barbarities about us.”

Not just Iglesias’s episodes of what the Buddhists call “youthful folly” but the growing pains of Podemos itself have provided ammunition for its powerful critics. The party’s early struggles to organize itself—establish a system of self-governance and articulate a platform—were particularly dispiriting. Factions formed almost immediately, and over time, faction fights led to the resignation or dismissal of all of the founding cadre except Iglesias himself. It seemed from a distance that part of the problem here was Iglesias’ determination to run a very tight ship, but he was also facing pressures towards extreme decentralization from the party’s anarchist wing and, of course, the fierce disagreements over the correct path common to leftist parties. All this led again and again to very public fights; mutual accusations of error, opportunism, and corruption; schisms, resignations, and dismissals; and bad press. Each split tore valuable activists away from the party at a time of particular shortage. And each dissuaded potential supporters from signing on.

The party has suffered as well from a number of questionable programmatic decisions. Its early commitments to dismantling the monarchy and tearing up the Constitution seem to have done it no good. Even the revelation of huge corruption within the royal family has not significantly increased support for abolition. And the demand for the framing of a new constitution proved even less popular. Indeed, Iglesias eventually reread the document and discovered within it impressive support for the sorts of social programs central to reviving social democracy—a constitutional right to decent housing, for instance. He no longer campaigns for its scrapping.

The position taken by the party in the Catalan Secession Crisis also seems to have cost Podemos support both in Catalonia and in the rest of Spain. The issue was whether Catalonia had a right to hold a unilateral (Catalans only) binding referendum on secession. Its opponents–PSOE, PP, and Ciudadanos–all argued that it did not and that they would oppose secession in any form. Podemos, in contrast, said that the Catalans did have this right (a very dubious position on constitutional grounds) but encouraged them not to secede, thus alienating both parties to the conflict. Each of these policies, and several others, can of course be defended on principle. But none was essential to the party’s core program and each was sure to meet with widespread disapproval: it’s hard to understand why they were promoted. But that’s the way it is with “youthful folly;” it’s hard to imagine any new movement or party avoiding such pitfalls.

The good news is that the party does seem to be learning from its errors. It is, for instance, centering its program more closely on addressing the immediate needs of Spain’s beleaguered working families. And it has suspended its efforts to win support by speaking the language of revolutionary populism and socialism. Iglesias concluded several years ago that his most radical dream–surpassing not only the pallid social democrats of PSOE and the neoliberal capitalists of PP, but capitalism itself–could not be part of his party’s public rhetoric. Very few Spaniards, he decided, would be ready to sign up for such a project. “If you say, ‘I’m running to put an end to capitalism,’” he told an El País interviewer back in 2016, all you’re doing is making yourself look ridiculous.” (See my Nov 25, 2016 Politics/ Letters post, “Podemos Stumbles.”) Since then, he has dedicated Podemos to the fight against neoliberalism and the reinvigoration of left social democracy. “I don’t believe,” he wrote in 2016, “that social democracy is an out-of-date label, not at all. A fourth social democracy, understood as the possibility of applying redistributive politics in the framework of the market to assure social protections and fiscal justice seems to me the best option for Spain.” Podemos, then, whatever its ultimate aims, is publicly committed to the relatively modest goal of establishing popular control over Spain’s capitalist economy. Iglesias’ touchstones are FDR’s New Deal, Danish Social Democracy, and programs such as Germany’s that make employees shareholders in the corporations for which they work and grant them seats on governing boards. This adjustment has not yet enabled Podemos to recover the popular support it had in its first moments, when all it stood for in the public eye was opposition to a corrupt political elite and an inefficient two-party system. But it has enabled it to take a seat at the table of governance alongside PSOE and to pull the larger party to the left on several important issues.

Unfortunately, Podemos’ chronic problems have continued to dog it during its first year in the government. The Dina Case, a perfect example of tabloid-ready melodrama, finds Iglesias caught in an intricate narrative that includes the theft of a cell phone containing compromising documents and sexually explicit photos, the politically motivated leaking of both to the press, the destruction of evidence, false testimony by the theft’s victim, and claims by Podemos’ now dismissed lawyer that the entire theft was staged to win the party public sympathy. The courts remain divided over whether the charges against Iglesias are at all credible, but the case has dragged on for months and continues its tortuous journey through the judicial system, tarnishing Iglesias’ reputation at the very moment when he might be enjoying his status as Vice President.

Worst of all, the coronavirus pandemic has left Podemos’s most cherished plans in disarray. By claiming a place as the junior partner in the coalition government, Podemos hoped to link up with progressive elements in PSOE, build out Spain’s modest and tattered “Escudo Social” (social shield), and turn Spain into something more like a vigorous, “New Deal,” social democracy. But almost immediately things became difficult. The pandemic hit Spain just weeks after the Coalition took power, and the collapse of tourism, the battering of other sectors of the economy, and the need to spend millions to cushion the social and economic effects of the pandemic left the government with mountains of debt. This debt in turn gave conservative circles in PSOE a pretext for trying to derail plans for restoring and extending social supports they had never really accepted. When Spain was granted 170 million Euros in “recovery’ funds by the Next Generation EU Recovery Plan, Podemos hoped to spend at least some of this to establish new long-term programs such as a national living wage. But this effort immediately came under attack not only from conservatives within PSOE and the entire Spanish right, but also from the powerful austerity bloc within the EU, which argued that the EU’s fiscal support could be used only to restore the status quo ante and build out the green and digital sectors of the economy and not to produce more robust regimes of regulation and social support.

This position, it now seems, has carried the day. The English edition of Spain’s El Pais reported in December that the EU Commission “is demanding to see a credible and coherent plan setting out Madrid’s reform agenda as part of the deal to release a recently approved package of European stimulus aid.” “‘Reform,’” El Pais continues, “is a loaded word, because in recent years it has been used as a euphemism to avoid the term “cuts,” and because it is associated with the austerity imposed during the 2008 financial crisis.” In other words, the EU will not only demand that Spain spend the funds it is granted solely to restore the existing system of supports and regulations, it will demand that it make cuts in key social programs at the same time.In its first year of something like power, then, Podemos is already facing the threat of a massive capital strike. And in this case, the threat is even more powerful than usual, because it comes come on top of the huge “natural” capital depletion produced by the pandemic.

Iglesias knows what is happening, just as he knows what it means to face a campaign of vilification and harassment by the combined forces of the right-wing parties, press, and social movements, and what it is like to build up a party from nothing under such conditions. He has seen other left wing governments—Greece’s, most recently—buckle in the face of such pressure. And he knows as well that the Spanish public seems to have lost the will for change that brought first the Indignados Movement and then Podemos into being. (He predicted, back in the party’s early days, that if and when the capitalist forces found a way to manage the Great Recession and repair the economy, the wave of popular resistance would lose momentum, and it would be decades before his party would have another chance.)

Of course, it is possible that Spain’s capitalists, and even Europe’s, may not be able to repair enough of the pandemic’s damage to satisfy public demands. Pain and rage are once again on the rise this winter. If this happens, Podemos may prevail after all, as it may if it can continue to work with the substantial left-wing of the PSOE, build out its relations with the powerful national unions, and drive roots into the communities where its support should lie.

Support might even be emerging where least expected, among the governments, conservative or social democratic, of the EU nations. A recent article in Spain’s respected center right digital daily El Confidencial reports that many European governments, having intervened aggressively to protect the economy and workers during the pandemic, “seem interested in maintaining their protagonistic role in the economy” rather that returning to the status quo ante of deregulation and small government. And what is even more surprising, “this shift is being welcomed by many voices of authority in the markets.” Could it be, then, that Iglesias’ “they” is itself turning leftward? If so, he and his party, perhaps even the Coalition itself, may find the path toward left social democracy much clearer than he presently imagines.

One concrete local sign of this possibility is the party’s success in taking the first step toward a guaranteed income for all Spaniards. Fighting resistance from within the Coalition last spring, Podemos still managed to push through an “Ingreso Minimo Vital” for the poorest Spaniards. This “minimum living income” was instituted not merely as a temporary measure to deal with the pandemic’s ravages, but an enduring part of Spain’s “system of protection,” its Escudo Social.

This is no small achievement, not only because of the help it will provide the neediest Spaniards, but also because it represents a first step in a potentially momentous shift. Spain, like the US and countries all around the world, seems destined either to find ways decouple basic income from the ever more precarious conditions of employment, as my colleague Jim Livingston argues, or to face democracy-destroying divisions between the conditions of the haves and have nots. It will be a crucial task of twenty-first century social democracy to achieve this goal.

The brief history of Podemos alerts us then, as do The Socialist Challenge Today and The Socialist Manifesto, to the daunting obstacles facing left movements that seek to govern today:

–Starting a modern political party is extraordinarily difficult: It involves building a nation-bridging organization, rooting it in thousands of local communities, and building a capable staff composed mostly of part-timers and volunteers. This organization can’t have the simple top-down decision-making and order-giving structure of a corporation: members expect to have a significant share in shaping the party’s program and choosing candidates and leaders. And the decisions to be made engage their deepest beliefs and dreams.

–Inevitably, then, as soon as this organization gets started, it will be riven by passionate internal disagreements and draw the fire of its powerful opponents on the right.

–Mistakes will be made, and the earliest mistakes are also likely to be the most egregious and definitive. But they can, over time, be corrected and survived.

–Working-class and poor voters can not be counted on to unite spontaneously behind left parties. Desmovilización is as much a problem for Podemos as it was–see Matt Karp’s excellent article “Bernie Sanders’s Five-Year War” in Jacobin—for the Sanders campaign.

–And any party that actually comes to power will face the threat of capital strike.

And yet, and yet. We see Podemos stumbling repeatedly yet making progress too. We see—and not just by looking at other moments in history–that while capital strike is indeed a daunting weapon it is not invincible. It has been fought before, during the periods of left social democratic ascendency in the mid-twentieth century, and it can be fought again, right now, as the neoliberal consensus shows signs of crumbling.

To my mind, then Panitch, Gindin, and Sunkara do not make an entirely convincing case for focusing left energies on the fight for socialism. Social democratic regimes, as they demonstrate, will indeed always live under the shadow of capital strike. But in this era of densely inter-related global exchange when emerging socialist nations will inevitably share the world stage with capitalist ones, so will socialist democracies, especially if they remain connected to the international market and participate vigorously in international trade and investment. Moreover, the left social democratic route Podemos follows today is not a diversion from the longer road laid out by Panitch, Gindin, and Sunkara. In fact, as they acknowledge, social democracy is a way point on the road to the more distant goal of socialism itself. I believe that Iglesias is still on that road; he tried to make the case for a postcapitalist Spain but found the price too high and has chosen to pursue the more proximate goals of left social democracy. Even these, he imagines, will take decades to achieve. But perhaps this assessment is too pessimistic, given the way things are going in Spain and Europe. In any event I’d argue, on this hopeful week in early January, Panitch, Gindin, Sunkara, and Iglesias provide us with an invaluable understanding of what it means to try to rebuild the left today. The debate between the paths they espouse should not (and has not, in the case of Jacobin, which Sunkara edits) preclude robust cooperation between left social democrats and socialists.