How often does something you read change your mind, or unsettle your beliefs? It happens to me every six months or so, when I venture into a field—ancient history, say—where I have no skills, only curiosity and anger, and I find myself in the midst of strangers who dazzle me with their confidence and erudition.

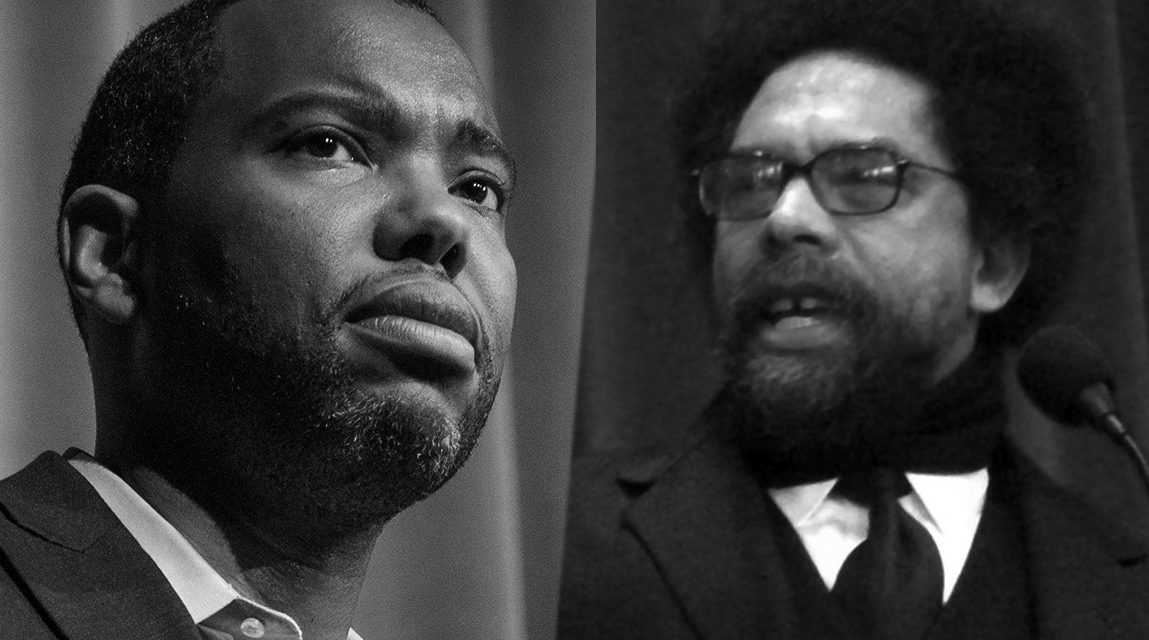

This is different. I have been defending Ta-Nehesi Coates against his critics on the grounds I thought were afforded by Harold Cruse, in The Crisis of the Negro Intellectual (1967)—a book that was renovating the tradition of black nationalism on grounds, Cruse believed, afforded by W. E. B. Du Bois. Now I have to rethink and restate those grounds., because Cornel West has forced me to.

That long, boring article in the Times (12/22) by John Eligon is not the place to start to understand the nature of the differences at stake—except when it gets to quoting Khalil G. Muhammad, formerly director of the Schomburg., on the difference between black radicalism and black nationalism. And the long, electric article in the Boston Review (12/22) by Robin D. G. Kelley is not the place to end, except as exhortation to an exploration of the same difference.

Of course MLK and Malcolm X are antecedents in the current debate. But this river runs deeper, all the way down to David Walker’s manifesto of 1829, when Africans declared themselves Americans with a rightful claim to every inch of America.

West criticizes Coates for not foregrounding capitalism in analyzing the sources and success of white supremacy. That is why he claims Coates “fetishizes white supremacy”—by treating it as an a-historical property of modernity rather than a historically specific feature of capitalism. West misses the point. Coates has plenty to say about capitalism, especially in “The Case for Reparations, “ where he documents the systematic plunder of black property by wholly legal but viciously racist means.

Coates isn’t evading the large and malignant problem of capitalism. Instead he’s claiming, correctly I think, that the Left’s insistence on the priority of class and class struggle is no way to address it. At any rate it’s not the way that black folk can go if they want to liberate themselves. The Popular Front model is a political and intellectual anachronism.

West also criticizes Coates for believing that freedom is individualistic—in other words, it’s merely liberal, a matter of formal legal rights rather than something that is collective and thus involves social solidarity with those who would resist the exploiters, whoever they may be. West again misses the point.

Coates, like Cruse and Malcolm and Du Bois before him, is not interested in the integration of American society and culture. He knows that black people don’t want to be like white people, or with them. So he believes that racial solidarity—with all its connotations of nationalism—is, and must be, much more significant than assimilation or upward mobility in the black freedom struggle.

In fact, it is West’s notion of freedom that is more individualistic. For it is rooted in the assimilation, uplift, and integration strategies of the civil rights movement, which assumed the upward mobility of black individuals was to be underwritten by changes at the law—which are, to be sure, imposed upon the powers that be by the activism of the people “out of doors,” in the streets. (This is what Kelley means when he summarizes West’s “major point” as a question: “how do we translate critique into action as opposed to readers’ self-pity or self-satisfaction with being ‘woke’?”)

Coates, like Du Bois, Malcolm, and Cruse, is more interested in creating equity between the white majority and the black minority—as in a diplomatic compact between nation-states. In this, not incidentally, he follows the example of Booker T. Washington, who understood that his people were a developing nation within a nation who needed both the military forbearance and foreign capital of the imperial metropolis, without which they might become victims of outright genocide or impoverished victims of illegal expropriation.

But West’s counter-notion of collective freedom is even more problematic. The working class can, I suppose, free itself of capitalist exploitation. Black folk can, I suppose, free themselves from white supremacy. Women can, I suppose, free themselves of male supremacy. But freedom, at least under modern conditions, means the right of every individual to make decisions for himself or herself—to control his or her body, to consent to the state’s exercise of power, to move freely through the world toward a destination not determined by his or her origins.

Freedom, so conceived, presupposes individualism, and vice versa. But don’t take my word for it. Go ask David Walker, or Sara Grimke, or Walt Whitman, or MLK, or Judith Butler.

That said, Du Bois’s great achievement in Dusk of Dawn (1940), which Cruse restated and enlarged in 1967, was to recognize that the three extant forms of struggle for black liberation were not working. These were nationalism (Walker, Delaney, Washington), assimilation (Niagara, the NAACP), and separation/back to Africa (Garvey). But Du Bois also recognized that by far the most popular form was Garvey’s.

What then was to be done? Du Bois suggested self-imposed cultural segregation—separation in one country, as it were, not a pan-African, Garvey-like project. “We have reached the end of an economic era, which seemed but a few years ago omnipotent and eternal,” he said. “We have lived to see the collapse of capitalism.” So black folk had to take advantage of their power as consumers, not as workers or property owners, to complete the transition to a new phase of civilization. In effect: throw away your buckets and throw down your dollars.

“There faces the American Negro therefore an intricate and subtle problem of combining into one object two difficult sets of facts: his present racial segregation, which despite anything he can do will persist for many decades; and his attempt by carefully planned and intelligent action to fit himself into the new economic organization which the world faces.” The “planned and deliberate self-segregation on the part of colored people” was one premise of this program. The use of their power as consumers was the other.

Cruse took up this argument The crisis of the Negro intellectual was that his or her identification with white academics or the Marxist tradition cut him or her off from the nationalist strain, and thus from the “black masses“ (a term Cruse used without apology). Cruse didn’t reject nationalism any more than Du Bois did. He periodized it—he treated it as a historical artifact worth thinking about, and with. He showed, for example, how and why Booker T. Washington was a (bourgeois) nationalist whose business acumen made Harlem the capital city of the New Negro through the Afro-American Realty Co., which bought enough property to accommodate the maroons who fled the Jim Crow South, ca. 1890-1930. Cruse also showed how and why Black Power was compromised by its infatuation with Marxism on the one hand and Third World guerilla movements on the other.

Like Du Bois, Cruse believed that the “cultural apparatus” (a term he borrowed from C. Wright Mills and Daniel Bell) was the soft underbelly of post-industrial capitalism. That was the site of struggle—the place we now call identity politics. That is where Coates is encamped. Like Cruse, Coates doubts that the Left’s insistence on the priority of class struggle in the opposition to capitalism has any purchase on the imaginations of Americans, black or white, and this despite his thorough knowledge of economic exploitation.

In these terms, Coates’s argument comprehends more of the intellectual tradition West calls the black freedom struggle. It treats black nationalism and black radicalism as two sides of the same coin—the struggle to liberate black folk from white supremacy without bleaching the culture, without erasing the differences between races in the name of a universal (white) norm.

And so it makes me rethink both the civil rights movement and Black Lives Matter. Perhaps it even suggests a new coinage in the making.