They gave us 48 hours to return home before all the airports in the country would shut down to contain the spread of Covid-19. There are huge numbers of us outside the mother country, numbers the size of which are mostly familiar to the Third World.

So I rushed home as the skies were being closed and barricaded, managing to catch the last flight back. Who leaves elderly parents alone in the mother country in times of crises? Not those from the Arab world. Not if you want to die easy. Not if you want to live easy, come to think of it. Not if you know what’s good for you. Never mind that one half or one quarter of the family will always be somewhere else as we run around between mother country and host. Never mind that some member of the family will always be waiting on that job, on this necessity, on that necessity; or that a large fraction of your life will always be spent running for that plane, making up for that missed time, thinking of elsewhere. This is the pace of life for many of us of who are semi-mobile: the professional labour, the economic migrants, the long-term students, the seasonal worker. Some can’t travel at all, of course. Those who can, travel back, spending a couple of days here, a week there, maybe months in isolation, then back to the Departures hall, or was it the Arrivals? One forgets. But we remember never knowing if we’re coming or going: used to being a statistic, used to being a series of ticks and crosses on boarding and landing cards, used to sighing over our “ghurba”, also used to being called lucky, because we are.

We are not the ones who can access the world simply by getting on a plane, not the ones who get their visas on arrival to their destination, or who, God forbid, travel visa-free, but we aren’t the refugees on the boats or in the camps, either. At the airports, we are the ones with the papers ready, the declaration checks checked, the locks on the suitcases unlocked, ready for inspection, the curls straightened, carrying lightweight bags and heavy hearts. We are ready at the visa offices with our long list of documents (originals, photocopies and some extra), the military exemption record, the proof of funds, the projected itinerary, the provisional travel ticket, the HR letter (Forgot to stamp it? Go back again), the letter of invitation from a friend –hell, the helpful friend himself perhaps in tow pressed against the window of the visa application officer. Here he is, Mr Benevolent Visa Officer. Here he is. Exhibit BF. The Best Friend with whom I will be travelling and staying in case you don’t accept the Airbnb booking slip in case the hotel booking is one day short in case the bank account has insufficient funds in case the ticket is provisional even though you told us not to buy a confirmed ticket because you cannot guarantee issuance of visa, and if you issue a visa, you cannot guarantee entry. Yes, we will sign that form that says we are not entitled. Yes, we will sign this form that says no guarantees. We are the ones who congratulate each other when the dreaded visa arrives. The longer the visa period, the warmer the congratulations. There are more of us than you think, from the cheap labour and seasonal worker to the rich tourist and venture capitalist and football star. How do I know? Because I’ve seen the visa lines.

For most people around the world, then, borders, if they aren’t closed off completely, are already hard to cross. We are used to slipping in through the gates by a hair’s breadth, at the last minute, or being the last number in the quota. We are used to panicking over travel documents locked away in embassies and visa offices that close at the easiest whim and don’t answer their emails or phones. We are used to being told to stand in the long queue not the short one, as we press our fingers to the machine time and time again, as we smile at the implacable neutral-faced border officers who are yes, we know, “just doing their jobs”. For many frequent travellers and migrants, it can best be described as a half-life, a journey of a lifetime spent as an in-between.

Still, even a border kept minimally ajar in peacetime is not the same as a border closed off entirely. At time of writing, the borders are shutting down for the urgent necessity of quarantine and lockdown, indicating or even causing –as locked borders inevitably do– job closures, means of livelihood, and family estrangement. This time, blocking rights of passage seems to be really for “everyone’s” safety. It’s not a security hang up; it’s not shorthand for xenophobia. (At least at the present time.)

Beyond the immediate effects, it is a sad moment for everyone, and not just because it has stirred up Europe’s memories of World War II. Only those, after all, who are supremely confident, and, this must be emphasised, supremely deceived about their place in the world, call for closed borders. It has taken a global epidemic to exemplify why lack of mobility is horrific even in peace time. After this is all over, one hopes the lesson won’t be forgotten.

Meanwhile, for those who already expect hurdles at border-crossing, it is an even sadder moment. It is only when freedom of mobility is taken for granted that one assumes reopening borders is a matter of time. The rest of the world won’t be wondering so much when they will be able to cross a certain border again, but if they will be allowed to cross it again. Taking the last flight out is watching the half-life that you live, being halved again, and there was precious little mobility to commend the half-life to begin with.

For the first time since World War II, too, the epicentre of the battle is located –momentarily– in the most advanced countries of the world while Africa watches. Yet as it has done before in history, as Europe struggles, Africa watches without Schadenfreude.

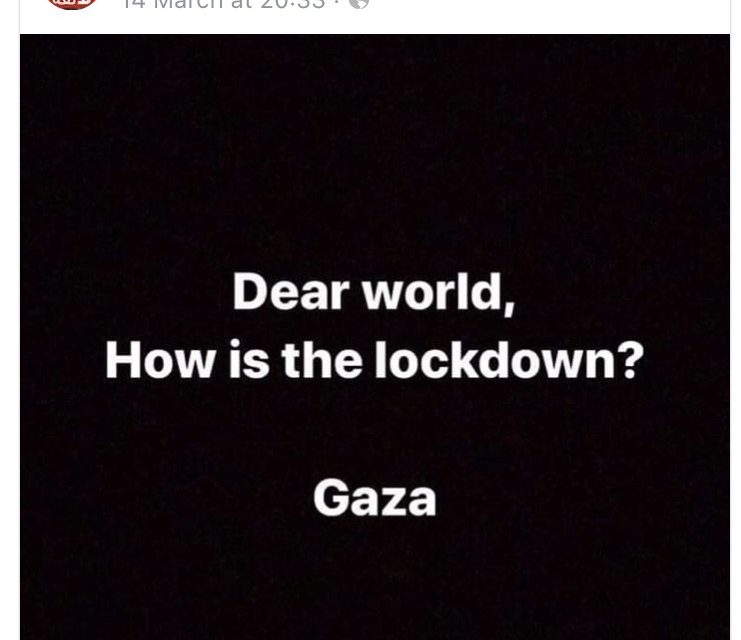

The jokes, of course, are there. African newspapers are cheekily accusing Europe of “Coronising” Africa. On social media, quite a few people last week seem to have got a kick off the Europeans being forbidden to enter the United States while the Middle Easterners were allowed in. Walk a mile in our shoes, the Africans thought. Walk a mile in our shoes, the Middle Easterners smirked. Walk a mile in our shoes, the Latinos scoffed. Across Northern Africa people are giving advice on how to survive lockdown based on experiences from 2011. One meme from Palestine, however, may have had the last word, even among other Middle Easterners: “Dear World, How’s the Lockdown? Yours, Gaza.”

Still, all these are jokes, whether in good taste or otherwise, or at best, effete comments. They aren’t the border controls against non-citizens that have gone up in Fortress Europe and City-Upon-a-Hill USA. They aren’t decisions made by decision-makers. They aren’t calls made at political rallies, or agendas presented by political parties, because of which the latter have gained landslide victories. They are at best jokes, and half-hearted ones at that. Because of course, the situation is temporary. It is gallows humour as we watch our own hard-to-leave borders close even further, and as we wait for the pandemic to overwhelm us in our own countries of origin. When that happens, we also know the media currently stoking the world’s panic will not mourn us or even cover us as it has the First World, although perhaps, judging by the amount of sensationalism some of the media has adopted in its coverage, the latter might be a good thing.

So as we take the last planes out, leaving some of our families behind yet again, this time we can’t help but wonder if we will see them again. Crises may be a good time to dream of alternate scenarios. Let’s dream for a moment. If Covid-19 had raged in Europe and America alone, would the Africans (north and south) open up their airports, their borders, their lands to the Europeans and Americans? Despite colonisation, despite indentured slavery, despite racist border controls, despite the difficulty of migration, despite the catastrophe of refuge, despite the wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Syria and the sanctions in Iran, despite being used as recently as last week as human missiles by Turkey and deflected as human missiles by the EU, despite potential economic incentives (“we need them more than they need us”) or inferiority complexes (“they’re more advanced”) –in short, despite the risk it might cause to the greater health or eventual exploitation of the tanned continent: would Africa still have kept its borders open to Europeans and Americans?

Whether for the better or for the worse, I think we have. I think we would.