[Originally published in The Architectural Review July/August 2018]

Frontal view of Casa IV.

Matola, a hamlet in the semi-desert of the southeastern Spanish province of Alicante, Valencia, is a tiny crossroads that sports a community centre, health club, hardware store, supermarket, bakery, and several bar-restaurants specialising in local rice dishes. Beyond this loose concentration of roadside businesses, however, lies a sprawl of large residential lots tightly enclosed by fences, gates and hedges that shield every style of house, from modest vernacular constructions to neo-neo-classicism or the latest in narco-Minimalist neo-Modernism, a style loosely inspired by Le Corbusier’s white period that seems to appear in Spanish news media whenever a drug lord or political leader is arrested.

The guest suite and patio-garden

Matola’s semi-rural residential fabric exemplifies a kind of exurban sprawl found throughout Europe. What makes Spanish exurbia unique, however, is that much of it consists of second homes. It is not unusual, especially in Valencia, for a family to live in a flat in town during the week, and to spend weekends and Spain’s long summer holiday period just outside town —sometimes only minutes away— in a rural retreat. For wealthier families, a third property on the coast, or even a fourth at a Pyrenees ski resort is not unheard of; real estate comprising one of Spain’s largest economic sectors, not to mention one of its cesspools of financial / political corruption.

View through the “porche” of Casa IV toward front yard and, to the left, the original house.

On a typical Matola rural lot of about a quarter of a hectare, Casa IV (no relation to Peter Eisenman) is an extension to a modest, single-story house of 1980s vintage. What makes Casa IV significant, in addition to its highly considered architectural design and its beautiful spaces and details, is a siting strategy that orders and structures a dispersed collection of pre-existing amenities: a driveway, carport, house, swimming pool, tennis court and garden shed; all sited on one large lawn surrounded by a hedge and chain-link fence; a microcosm of the larger sprawl beyond. The project transforms its site into a rich landscape of semi-enclosed garden spaces, each with its own distinct quality, degree of intimacy, and micro-climate. A work of “landscape architecture” in the fullest sense of the term, Casa IV exemplifies how even a relatively small architectural object can create coherence beyond its walls; becoming much more than merely a figure against an assumedly neutral ground.

Guest suite

The brief presented to Mesura Arquitectura by the client, a Barcelona family with three grown-up children and roots in the nearby town of Elche, was to enlarge an inherited house used as a holiday home. Concretely, a new guest suite at the back and an expansion of the house’s porche, an exterior dining room typically situated in a corner of a Valencian house and protected from the sun by a generous overhanging roof (in Spain, the Sunday family meal is typically a mid-day rather than an evening feast). The brief sums up the scenario of a house becoming too small when the sentimental partners of grown up children and eventually grandchildren start to show up at family get-togethers.

Site plan of Casa IV. Image courtesy mesura.eu

As Mesura founding partner Benjamín Iborra explains, however, the idea of “adding extensions” onto two sides of a house to make it larger was questioned. Not because the house was worth preserving in its original state for reasons of heritage, but because it would inevitably result in an architectural mishmash. The solution that emerged was to consolidate the client’s wishes in a single new volume attached minimally to the existing house, and to design it as a work of “garden architecture” to establish “a sense of hierarchy” —as Iborra puts it— on the entire property. The idea of using a garden element to expand a building has a significant precedent: Porto’s Casa das Artes, by Eduardo Souto de Moura, is an art museum enlargement contained within an elongated, opaque stone construction at a property edge that is effectively a “garden wall” framing the historic palace and its grounds.

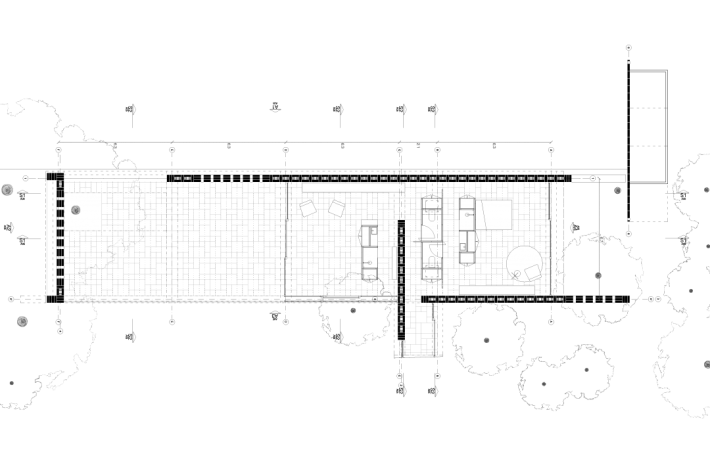

Floor plan of Casa IV. Image courtesy mesura.eu

Casa IV is essentially an elongated brick and concrete garden pavilion that roughly divides its site into two halves: a front half for the original house and pool, and a rear half for the tennis court. These areas are further subdivided by free-standing brick walls that perform interchangeably as garden walls, exterior walls, or indoor partitions, not unlike the walls of Mies van der Rohe’s early houses or the Barcelona Pavilion. The brick walls also act as structural supports for a row of four handsome cast-in-place concrete vaults, bringing to mind La Ricarda by Antonio Bonet, a villa completed outside Barcelona in the late 1950s characterised by a systemic repetition of vaulted modules that creates a surprising variety of spaces both inside and out. “Yes, Bonet is a reference for us, but so are Sert, Kahn, Eduardo de Almeida, and the revolutionary art schools of Cuba,” acknowledges Iborra. Casa IV’s rigorous systemic modular repetition, be it that of a brick, a wall or a vault, can be read as a brick-and-mortar manifesto for a more archaic tectonic sensibility in an architectural age in which “anything goes” thanks to the seemingly endless technological possibilities at our disposal. Indeed, the firm’s very name, “mesura,” is a Spanish word meaning moderation or restraint.

Sections of Casa IV. Image courtesy mesura.eu

Entry to the Casa IV garden pavilion is through the house, the central corridor of which connects with a glass passageway, duly equipped with sliding doors on each side, that in turn leads to another corridor inside the new structure, this one between two brick walls. On one side of this corridor is the private guest suite, on the other the porche, a part of which can be closed off by glass sliding doors and wooden privacy shutters to create a cozy indoor lounge in winter. Sheltered by three of the pavilion’s four vaults, the new porche turns its back to the tennis court with a long brick wall that eliminates the need for chain-link fencing along one edge of the court. The front of the porche, by contrast, faces the house and pool through a 17m-long clear-span opening, a structural feat achieved by means of a monumental concrete girder nearly 1.5m deep from which cross beams supporting the three vaults are suspended. The girder’s depth coincides with the height of the vaults, hiding them from the front garden, to be revealed only when you enter the porch. The vaults, undoubtedly the most delightful feature of Casa IV, are a revelation when visiting for the first time. “Why give it all away at first glance?”, asks Iborra rhetorically, adding: “architecture is an experience, so it has to reveal itself gradually.” Details too: the shape of the artisanal Roman brick used throughout and the Flemish coursing variation were designed so that whole bricks would be used throughout. No bricks were severed during the construction of Casa IV. Reassuring.

Conceptual representation of Casa IV. Image courtesy mesura.eu

Inhabited now for over a year, Casa IV has undergone an important transformation since its completion: the so-called “guest suite” is now the principal bedroom, the owners having decided that they wanted it for themselves. This has converted Casa IV into an integral (if not everyday) component of this (second) home. Indeed, Mesura also renovated the interior of the existing house, but these alterations are relatively low-key in their expressivity. “We didn’t feel this was the place to make a statement,” affirms Iborra. The clients recount that the family had become attached to the original house over the decades, and that, despite initial misgivings, it was indeed a good idea to consolidate the expansion program within a new, nearly separate structure. “The new dignifies the original, and indeed the entire place,” explains co-owner Belinda.

Architectural pavilions have become a thing in recent times, with art collectors buying and selling them on the art market as if they were pedestal sculptures, which many effectively are. This pavilion, however, is highly site-specific, creating space around it as much as within. The exterior spaces it forms are seamless extensions of its interior spaces, making it inseparable from the site. Again, the Barcelona Pavilion comes to mind as a precedent that structures the larger site it occupies, and that would not make sense elsewhere.

Casa IV goes beyond accommodating a functional program to structuring and ordering the various disparate elements surrounding it, so demonstrating that at its best, architecture can have a positive effect well beyond its traditional purview: the building. As such, Casa IV transcends “architecture” in the strictest sense, and enters the realm of landscape, even urbanism. Taken to a larger scale, such an architecture of effectivity rather than effects could go some way toward actually defeating sprawl, no matter what kind.

Source: Criticalista