Woodstock, Altamont, and the Sixties

David R. Shumway

Last August, we celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of the Woodstock festival, and analyses of the event’s significance were seemingly everywhere. Most took the event seriously, and my impression is that most commentators saw the event in positive terms. What was notably missing from these discussions, however, was the second part of the narrative that emerged in 1969, the one that ends at the December 6th Altamont festival, where one of the attendees, Meredith Hunter, was stabbed to death by Hell’s Angels who were engaged to provide security for the performers. The cultural significance of Woodstock changed as a result. Where Woodstock had been celebrated in the media as evidence of positive influence of the counter culture or the distinctive character of the younger generation, Altamont became grounds to reject these judgments. Woodstock, as Joni Mitchell’s song had it, wanted to take us back to the Garden, and the media seemed to accept that it had. After Altamont, the media substituted a vision of human evil, even original sin, and the need for traditional order.

I want to retell the story of these two festivals in materialist rather than metaphysical terms.

In August of 1969, interpretations of Woodstock focused on two themes. The first was disaster, and the second was good behavior. In some versions, the festival was called a disaster, and Joel Slevin has recently reaffirmed that judgment. In other renderings, the emphasis was that a disaster had been averted. Both versions take as their premise the poor planning of the festival promoters and the incomplete preparation for the festival caused by lengthy delays in finding a location for the event. The lack of fencing around the site meant that it would have been impossible to carefully control admission even under the best of circumstances, and the promoters early on abandoned the idea of requiring tickets. But the main problem was that attendance was far greater than the promoters or anyone else might have predicted. As a result, the roads approaching the festival site, including NY 17, a divided highway, were gridlocked. There was not enough food, sanitary facilities, first aid, or space for camping. Though the festival took place outside, with musicians performing on what was only a partially covered stage, no provisions had been made to deal with rain, much less thunderstorms. County authorities declared a state of emergency, and personnel from the nearby Stewart Airforce Base helped to airlift performers and medical evacuees. The New York Times ran an editorial titled “Nightmare in the Catskills,” and headlines in the Daily News featured the traffic and the mud.

But if disaster was the first take on the festival, the narrative shifted after it was over to focus on the remarkable fact that nothing bad seemed to have come of the “disaster.” On August 25th, the Times ran an article reconsidering the festival that featured interviews with six attendees. The article asserted, “the young people were not only oblivious to the discomfort, but they also were surprisingly well-behaved for so great a crowd, at peace with themselves almost to the point of ecstasy.” In the months that followed, the standard media narrative of the festival seemed to follow the lead of Max Yasgur, the farmer who owned land on which the festival was held, when he spoke to the crowd from the festival stage: “the important thing that you’ve proven to the world is that . . . a half million young people can get together and have three days of fun and music and have nothing but fun and music.”

Yasgur’s proclamation reveals important elements of the meaning that Woodstock was accorded in the months following the festival. The first is that the event did indeed prove something to the world; it wasn’t just mere chance, but something essential that was responsible for the harmony that existed among the crowd despite what seemed to outsiders, and even the festival promotors, extreme hardship. But what was responsible for the extraordinary good behavior of the crowd? Here the media seems to have largely depended on two implicit explanations. One was generational: those who attended Woodstock were different than their predecessors—the teenagers of the 1950s who were often depicted as juvenile delinquents—because of unnamed changes in society or culture. The second implicit explanation was that the counter-culture had a broad positive influence on the youth of the time. Both explanations, which didn’t necessarily exclude each other, portended a better society. The lesson of Woodstock was that the young people of the time really were different, and that difference would be the foundation of implicitly far-reaching transformation. It is almost as if the media were expecting that the age of Aquarius would actually come to pass.

There is, of course, a problem at the root of these explanations, which is that they base their claims on a single example. A little bit of comparison might have tempered the optimism. While most other festivals had not been notably violent, some, such as the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival, which for the first time featured rock bands as well as more traditional jazz performers, had been less than idyllic. Held a month earlier, the Newport festival attracted around 20,000 ticketless young people who were described in the Times as being involved in a “rock-throwing battle with security guards” and in gate crashing that “drove paying customers from their seats.”

If you are reasoning from a set of one, then a second instance almost necessarily will be taken as evidence that your previous conclusions were entirely mistaken. That is what happened in the wake of Altamont, which has gone down in history as “the end of the 1960s,” meaning that the decade’s association with positive change had been an illusion. If the success of Woodstock was communicated effectively by the documentary film Woodstock (Michael Wadleigh, 1970), the counter-narrative was also disseminated in the documentary Gimme Shelter (Albert Maysles, David Maysles, Charlotte Zwerin, 1970). Both films probably attracted far more viewers as concert films than for their contextualization of the performances, but each did communicate a different version of the 1960s. For most of intervening years, the Gimme Shelter take was more influential.

In the face of the Altamont revision, Woodstock suffered quite badly. John Morthland’s piece on “Rock Festivals” in the Rolling Stone Illustrated History of Rock & Roll is quite a negative take on the entire phenomenon (in part because it seems more interested in profits than performance), and in a parenthetical remark, it dismisses the Aquarian Exposition: “There had been deaths at Woodstock, but they had been conveniently overlooked in all the romantic youth-cult hype.” Once such hype was exposed, Woodstock became at best a good party. The attendees were likened to guests at a frat party in their hedonism and in their lack of social consciousness. “Nothing but fun and music” now seemed to express the festival’s triviality.

The fiftieth anniversary representations of Woodstock began to make some headway against the either/or narratives pitting Eden against Satan. Perhaps the most important of these was the PBS documentary Woodstock (Barak Goodman, Jamila Ephron, 2019), which gives the festival a political edge rare in previous representations. While the film’s subtitle, “Three Days that Defined a Generation,” makes it sound as though it might merely repeat the original generational account, in fact it uses numerous interviews with participants at all levels to show that the festival was a manifestation of the peace (or anti-Vietnam War) movement. Evidence for this had always been available, but the media largely ignored it. In the Times’s reconsideration, two of the six attendees interviewed mention a connection between the festival and peace marches. The interviewer chooses not to follow up on these suggestions, which were provoked by a question about having experienced before the feelings of community the festival had produced in the subjects. But the link to the peace movement is there on the festival poster, which promises “3 Days of Peace & Music” and which features the image of dove perched on the neck of a guitar. “Peace,” of course, is a double-entendre, pertaining at one level to the pastoral setting, but at another, this being 1969, to what a large minority of Americans had been actively demanding in protests peaceful and otherwise. Moreover, in the performances (which were preserved on film and record) there are many references to the anti-war position, from Joan Baez extolling her draft-resister husband’s organizing in prison, to Country Joe and Fish’s “Feelin’ Like I’m Fixin’ to Die,” and Jimi Hendrix’s concluding improvisation on the “Star Spangled Banner.” None of these overtly anti-war statements provoked any dissent from the crowd.

To recognize Woodstock as a political event, however, is also, alas, to recognize that it was not representative of a generation. It is true that by the summer of 1969, Americans of all political persuasions were tiring of the Vietnam War, and a majority of those polled in June of that year favored a phased pull-out of U.S. troops. But nearly 50% of them also expressed approval of President Richard Nixon’s handling of the war while only around 25% disapproved of it. And this division was not mainly generational. While it is likely that young people opposed the war in larger numbers than their parents, it is not at all clear that the majority of the young did so. In the Connecticut high school I attended, which drew from a traditionally Democratic working-class community and a historically Republican suburban one, active opposition to war involved only small minority. The male children of the working class were those most likely to be drafted and the least likely to oppose the war; the children of the suburban Republicans mostly shared their parents’ support for the war. Going to Woodstock defined one as a member of the opposition, as a member of political minority.

One way to account for the harmony at Woodstock, then, is to recognize that people chose to go there for peace in both senses. The audience self-selected for harmony. But the audience was homogeneous in ways that go beyond their ideological agreement. The audience at Woodstock was overwhelmingly white and middleclass, and it was predominantly male. Children of the middleclass, especially the upper middleclass, were the bedrock of the anti-war movement and served as the leadership of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the largest New Left organization. Most of the performers that Woodstock featured had young white men as their primary audience. Moreover, although the majority came to Woodstock without paying for tickets, getting there required most to spend some money. While doubtless some hitch-hiked, most drove or rode with friends. We can surmise this from the traffic jam the festival created, and vast amount of land given over to parking in the vicinity of the festival. Because I spent several hours on the Sunday of the festival wandering around the parking areas hoping to run into friends from Harrisburg, PA, where I lived before moving to Connecticut in 1966 (I didn’t find them), I know that most people came from the cities and the suburbs of the Northeast. The states of New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut were most strongly represented, with others from eastern Pennsylvania and the Boston area. So Woodstock festival goers were also similar in race and class, meaning that the larger social conflicts that affected America at this time were largely absent from the event.

None of these conditions applied at Altamont. That event, which was originally planned not as festival but as a “free concert,” never made any ideological claims. It was from the start, it could be argued, a more transactional event, in that the Rolling Stones, the primary movers behind the event, wanted to perform a free concert in order to counter the bad publicity they received for what were regarded as excessively high ticket prices during their tour of the U.S. Thus, Altamont attendees came together not celebrate Aquarius or nature, but to get something for nothing. The free concert was originally planned for Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, a site where the Grateful Dead and other groups from the region had previously played free shows. Had the event taken place there, the existing community for such events might well have produced a better outcome. But a permit could not be obtained, and only at the last minute was the Altamont Speedway made available. It is located in Tracy, California in San Joaquin County, about 70 miles from San Francisco. The region around the Tracy was rural, but it was not a pastoral retreat in the sense of White Lake. It was rather a dry landscape, with even less infrastructure to support a large crowd of transient concert goers. All evidence suggests that the crowd at Altamont was far more diverse from a class perspective, and somewhat more from a racial one. American social conflicts were well represented in the Altamont crowd.

The violence at Altamont reflects the violence that remained at the heart of American society in 1969. The victim was an African American, and his assailants were white Hell’s Angels. The presence of the Angels as “security” was partly a reflection of the Grateful Dead’s unwillingness to recognize the group as antithetical to their own vision, but it brought a different subculture into the midst of the festival, more or less ensuring conflict that Woodstock’s homogeneous audience excluded. The standard narrative misinterpreted both events. It failed to recognize that Woodstock represented one side in a cultural and political struggle coming together to celebrate itself, while Altamont represented a more random sample of Americans who shared little except the desire to hear some free music.

The 1960s were a period of radical change that continues to influence us today. These changes in manners, morals, and the perception of social inequality provide the ground for the political strife of 2019. While we often give the 1960s credit for more recent liberalism, the decade was also when the New Right was born out of the ashes of Barry Goldwater’s defeat. Nixon’s silent majority became the religious right’s moral majority which arose in opposition to racial and gender equality. Woodstock accurately reflected some of the cultural and political changes that were in process in the 1960s, while Altamont reflected the social conflicts that the decade didn’t resolve or created anew. The misreading of Woodstock as reflecting the whole society produced the misreading Altamont as its dark mirror.

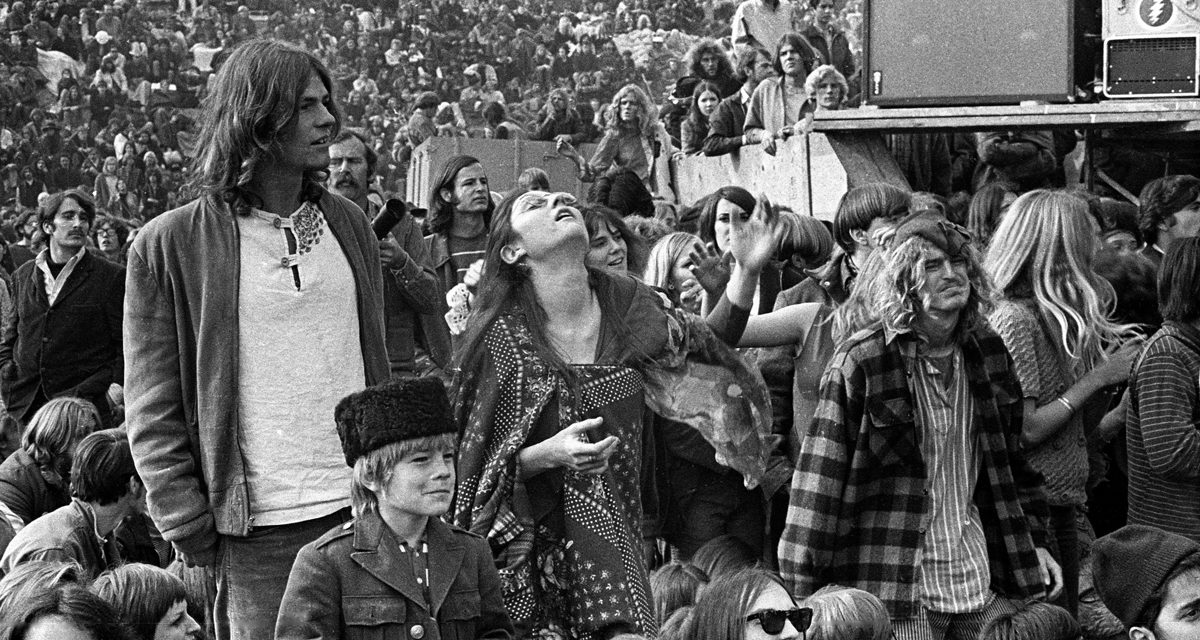

Image Credits: Getty Images, Robert Altman, 1969