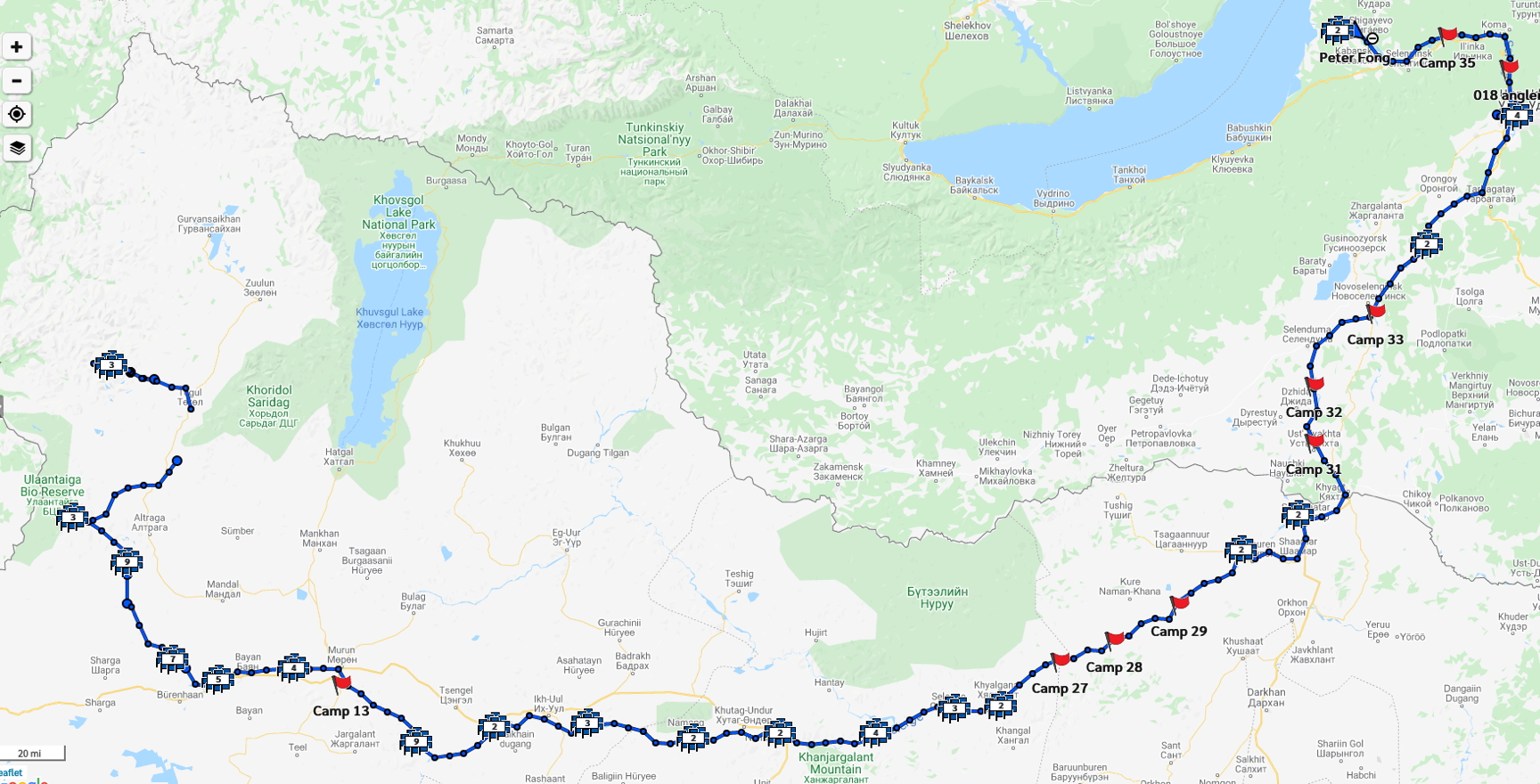

In 2018, Peter Fong, writer, photographer, ecological activist, and Head Guide for the Mongolia River Outfitters, organized The Baikal Headwaters Expedition, a thousand mile row down the Selenga River across Mongolia to Lake Baikal in Russia. The Selenga provides more than half the water that flows into Lake Baikal, the world’s deepest and most voluminous lake and repository of one-fifth of the world’s fresh water. That water and the life forms it supports are threatened by the Mongolian government’s plans to dam the river for hydroelectric production and tap it for mining operations and far-off cities. And so, of course, is the Selenga’s magnificent beauty, its singular aquatic life (including the Taimen, a trout that can grow to 5 or 6 feet in length and live for 5 or 6 decades), and the people who have lived on the river’s shores since time immemorial. Peter and his team spent three months rowing down the Selenga, studying the flora and fauna, sleeping rough, and getting to know people all along their way. The story that follows gives a sense of expedition life, with its challenges, surprises, ordeals, and magic. And it’s a powerful parable of the terms of struggle for the planet in our times.

When I reached Peter to ask him for a piece of the longer account he is writing on the Selenga journey, he was just back home (in Tangiers) from a shorter expedition, this one into Morocco’s Atlas Mountains, in search of a “remnant trout” that was stranded at the end of the last Ice Age. Another waterways story.

–John McClure

As the 2018 Baikal Headwaters Expedition neared the Russian border, we began to receive anxious messages from our contacts in Buryatia. One dated September 14 contained the following warnings: 1) “The temperatures are starting to drop really fast over here”; 2) “if you come to Russia, it’s better to leave your boat in Mongolia”; 3) “if you come and try to perform scientific research here, you guys and people who work with you will most likely get into big trouble”; and 4) “As far as getting the permission to float the river, it also doesn’t seem to be possible.”

Heeding this advice, we sent all of our scientific samples and equipment south to Mongolia’s capital, Ulaanbaatar, and resolved to enter Russia as tourists. We would still arrange a few informal meetings with fisheries researchers, but we planned to avoid attention of any kind. Meaning no more stops on shore to administer questionnaires, no further collecting of aquatic insects, and no pilgrimage to the graves of two of the original Decembrists, the anti-czarist revolutionaries who took inspiration from the fledgling U.S. Constitution. And absolutely no more standing up in the drift boat with our fly rods, casting oversized streamer patterns for taimen, the world’s largest trout. We would make our way downriver as quietly as muskrats (an invasive species in this part of the world), then leave Siberia with all due haste.

It was not therefore a surprise to reach our takeout point at Istomino—a little village on the shore of Lake Baikal, just southwest of the Selenga Delta—and see nobody. Not a single soul. Our original plans for press releases and publicity campaigns, like many of the bright and cheerful schemes germinated so many months ago, had been overtaken by the real-world clouds of nationalism and great-power politics. On top of all that, there was a winter storm in progress—on the fourth day of October. The wind was blowing twenty knots, with gusts to thirty-five, driving dun-colored waves over the near-shore sand bars and onto the grassy bank. A van that Anton had commissioned to pick us up had mistakenly stopped in Istok, the next village to the west.

While I’d been rowing into the sleet and snow, working hard at the oars, I’d felt damp but warm. Once the long hours of rowing were over, my body got cold fast. I knew that disassembling the boat would take some time, and also knew that I couldn’t properly wield a wrench while shivering uncontrollably. So I grabbed a waterproof duffel with my remaining dry clothes and headed for the nearest available shelter: a long wooden fence, head-high, a few boards blown loose by the storm but otherwise upright. I knelt there in the lee of the fence, grateful for this partial respite from the wind, then pulled off my rainjacket and waders. As my numb fingers fumbled with buckles and zippers, I kept my head down, as if that might somehow fend off the snow. A raven croaked above me, the first sign of life I’d heard since rousting a flock of ducks from a marshy patch of the delta, miles ago.

When I was a much younger man, black birds seemed to pay me an unusual amount of attention. Once, while reclining in a hilltop meadow on Martha’s Vineyard, a crow landed on my foot. The bird’s brown eyes shone close and I could hear the rustle of the jet-black wings as they folded. The crow pecked and pulled at my shoe, as if trying to untie the laces. Then it began sidestepping along my leg, the head bobbing up and down with a curious undulating motion, drawing my attention to the dark, glossy hackles on its neck. The bird opened its beak but silently closed it, spread its wings but made no move to fly. It seemed to choke, then regurgitated a small stone, which bounced off my thigh and into the grass.

Now that my own hackles have long gone gray, the black birds seem to notice me less. But I still like to watch them and read about them. One of my favorite recent stories is Mongolian writer J. Dashdondog’s “The Old Woman Who Speaks with Ravens,” which describes the birds as “messengers from heaven.”

The next croak came from just over my left shoulder. I was still struggling with my fresh layers, the dry fabric catching on my wet skin like silk on a rough-hewn board. Nevertheless I turned my head upward and toward the sound, expecting to see an intelligent black bird perched on a fencepost. Instead I saw the weathered face of a skinny old man. He was wearing a Cold War–era chemical protection suit—with the olive-green hood, but without the mask.

The old man croaked again. The sound was sharp and urgent and not unfriendly. I greeted him in English and Russian while continuing to alternately shrug and wriggle into my raingear. Eventually I managed to stand up and face him, feeling as happily disoriented as anyone who has just completed the journey of a lifetime has a right to be.

By signs and gestures, the old man gave me to understand that he was deaf and also without the use of speech. He watched curiously as I jumped up and down and flapped my arms, trying to warm my hands and feet. Then the questions started. He mimed the swing of a shotgun. Had I been hunting for ducks? I shook my head. Then he cast an imaginary rod and cranked on an illusory reel. Had I been fishing? No, I admitted.

Now it was the old man’s turn to shake his head. His eyes were bright with amusement. One finger corkscrewed under his stubbled chin. The message was plain: You, my son, are crazy.

I laughed and he croaked, but softly, a low chuckle. I ran back to the water’s edge and started in on the nuts and bolts that had held the boat together for fifty days and fifteen hundred kilometers. The old man lifted up a loose board and propped it against a gatepost, then shuffled off along the fence. By the time I looked up again, he had disappeared.

created by dji camera