Photo courtesy of Frances Negrón-Muntaner

More than a month into a government-mandated curfew that began on March 16, it remains unclear if the coronavirus outbreak in Puerto Rico will become another catastrophic turning point. Some believe it is inevitable due to the archipelago’s multiple “pre-existing conditions.” In addition to being legally subject to US Congressional sovereignty, these include a high proportion of residents who are older or suffer from illnesses, a limited number of medical personnel and hospital beds, numerous people in unsafe living situations due to gender violence or homelessness, and a profiteering and neglectful government. But unlike many in the United States and elsewhere, Puerto Ricans are not in shock nor consider the neoliberal state’s disregard for life new or exceptional. Throughout the last decade, grassroots politics in Puerto Rico have mainly centered on what most of humanity is attempting to do now: staying alive.

Encompassing at least three dimensions—defending life, living fully, and joy in justice—the collective move to a politics of being arises from several intertwined catastrophes stemming from the so-called “debt crisis.” In the making since the 1970s, the crisis erupted into global awareness in 2015, when then-governor Alejandro García Padilla announced that Puerto Rico had amassed such a staggering debt—$72 billion, plus $50 billion in pension obligations—that it was “unpayable.” The debt derives in part from the ten-year (1996-2006) phaseout of Section 936 of the US Internal Revenue Code which sought to assure high-profit margins to American corporations that operated in Puerto Rico by extending tax breaks. Congress abolished the tax exemptions to fund an increase of the minimum wage stateside, inducing a wave of plant closings, the loss of over 100,000 jobs, and a deeper recession in Puerto Rico than the one experienced in the United States.

Whereas the creation of the debt is in itself indicative of a larger political crisis, it was the US response that officially transformed “la deuda” into “la crisis.” Dismissing alternatives proposed by Senator Bernie Sanders and others that supported debt relief and equitable access to resources, the US Congress passed the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability (PROMESA, HR5278, 2016) which returned the island to a direct form of colonial rule. The bill created a fiscal control board composed of seven appointees with deep ties to the banking industry—including entities directly involved in producing the debt. The fundamental goal of “la junta,” as Puerto Ricans pejoratively call the board, is to extract payment through privatization and austerity cuts to services and critical needs such as health care, education, infrastructure, and pensions at whatever cost.

Then came María, a category-five storm that made landfall in Puerto Rico on September 16, 2017. Maria exposed the ravages of neoliberal-colonial governance by demolishing the archipelago’s decrepit electricity network, ushering an almost year-long energy blackout, and leaving half a million residents with damaged or destroyed homes. Underscoring that there is no such thing as a “natural disaster,” the federal and island governments opened the gates for disaster capitalism and refused to provide adequate or timely assistance, resulting in hunger, homelessness, and the deaths of at least 4,645 people. In addition, Maria’s aftermath brought about the migration of over 120,000 residents—about 4 percent of the population. Poverty rates soared to near 50 percent.

Two years later, came the “swarm”: more than 3,000 earthquakes that have been jolting Puerto Rico since 2019. Even if it was hard to imagine, on December 7, those closest to the epicenter felt the ground beneath their feet not only vibrate but collapse in every sense. At dawn, a powerful 6.4 earthquake on the Richter scale knocked out electricity throughout Puerto Rico for several days and razed neighborhoods on the southeast coast. The swarm has to date killed four people, damaged 33,000 homes in 33 municipalities, rendered more than 2,000 people homeless, and forced another 8,000 to sleep outdoors or in makeshift shelters for fear that walls or roofs would crash down next. Although the state restored electricity within a week, the situation remains critical. Thousands of people still live on the street, and parts of the island continue to experience significant seismic activity. As recently as May 2, a 5.5 earthquake rocked Ponce and adjacent municipalities, displacing fifty families and shattering historic buildings, including the Ponce Massacre Memorial Museum.

If not as deadly as Maria and less reflected on, the swarms have been acutely transformative. To start, Puerto Ricans learned that enduring earthquakes is cognitively different than surviving hurricanes. A storm can be devastating, yet residents can anticipate it, know that it will be over in a few days and that it rarely strikes twice. The fact that meteorologists assign hurricanes proper names to facilitate emergency responses casts them as characters in a shared narrative. In the case of Maria, even the storm’s name was particularly familiar: it immediately recalled the Virgin Mary, the classic soap opera El hijo de Ángela María, and the girl named María from West Side Story (1961). In contrast, tremors can number in the hundreds and arise without warning or have a discernible end. Nameless and aimless, quakes can similarly annihilate people and property in mere seconds. In shaking poorly built structures, already weakened by the hurricane, the 2019 temblors further exposed that the majority of homes, schools, and buildings in Puerto Rico are not up to code, thus turning seemingly sound concrete shelters into possible sarcophagi.

Moreover, the swarm clarified a political dimension that Maria had not entirely illuminated: “the South exists too.” In other words, María’s initial impact was geographically indiscriminate. The entire Puerto Rican archipelago remained in darkness for months, and much of it without water, social services, or government support. While the post-Maria “recovery” was uneven, the tremors and aftershocks highlighted not only latent hierarchies among regions but also that these continue to deepen as the neoliberal project progresses. This unfolding reproduces the colonial relations between Puerto Rico and the United States, as well as the coloniality of power between the capital, San Juan, and the rest of the island.

The phenomenon is evident in the most affected municipalities, such as Guánica, Ponce, or Yauco, are not part of the real estate boom of neighborhoods in Old San Juan or El Condado. In the latter areas, there is a shortage of real estate for sale, prices of one-bedroom apartments surpass half a million dollars, and buyers pay cash. Meanwhile, in Guánica, 65% of the residents and 82% of the children subsist below the poverty level. As of March, 800 families had left Yauco partly because the government of Puerto Rico had made no new efforts to reopen the schools or provide recovery resources even if has accumulated a 9 billion-dollar reserve fund to pay the debt. For both capital and state, the areas that Puerto Ricans condescendingly refer to as “la isla”, that is, much of the geography beyond San Juan, do not count.

The government’s response to the earthquakes likewise confirmed that the abandonment of life inflicted on Puerto Ricans goes beyond simple political incompetence. Instead, it demonstrated that neoliberalism is, besides a logic of extraction, a necropolitical project led by transnational elites that constitutes a distinct colonial-capitalist normality. As I have argued elsewhere, since the United States invaded Puerto Rico, various sectors of capital have subjected the island to three different forms of colonial extraction: agricultural (1898-1945), manufacturing (1945-2006), and now neoliberal debt (2006-present). In some ways, the more recent iteration may be the most injurious. Articulating the interests of finance, real estate, and tourism sectors of capital, it not only aims to profit, privatize, or expel labor but to set the stage for an “empty island”: one devoid of Puerto Ricans.

In this latest mutation of colonial-capitalism, the notion of “privatization” acquires multiple meanings. Aside from referring to how the state and capital expand neoliberalism, privatization increasingly implies the internalizing of colonial-capitalism, that is, the driving of its logic deeper into bodies and spaces. Through disavowal and a slow pace of action, the capitalist state transfers the responsibility for sustaining life and maintaining infrastructure to the same affected, displaced, and dispossessed people, including its diaspora. The process encompasses the already mentioned abandonment of the island’s interior, deemed unprofitable, as well as the denial of state resources that all citizens are legally owed, even within the current framework of colonial citizenship.

For instance, nearly three years after Maria, President Donald Trump, Secretary Ben Carson of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), and Peter Gaynor, Acting Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), continued to withhold the $36 billion in recovery funds for Puerto Rico approved by Congress. After political pressure finally became unbearable as the earthquakes raged, the Trump administration released a mere fraction: $1.5 billion. Moreover, they ensured that the funds would not be entirely available by imposing conditions on Puerto Rico that did not apply to the states facing similar disasters. Among them, the requirement that emergency procurements have to be approved by the Fiscal Control Board; the suspension of the $15 minimum wage for federally contracted workers; and a ban against deploying funds to improve electrical infrastructure, even though the resources designated for this purpose have still not materialized.

In addition to restricting resources, the process of internalization strips people and communities of their limited income in the retail market, almost entirely dominated by US corporations. In this context, Puerto Rican residents have little option but to patronize Walmart, Costco, and Walgreens to buy survival items that the state refuses to provide during times of emergency such as water, tents, and batteries.

Internalization, however, goes beyond the privatization of resources or the forsaking of populations: it also includes the bodily ingestion of colonial-capitalist violence, which further threatens physical and mental health. Increasingly, Puerto Ricans not only lose their homes and watch their relatives die, but they can track in real-time how neither the federal nor the island governments value their lives and have no qualms about letting them die. As María, a Yauco resident who was living in a tent after the December quakes and has attempted suicide on several occasions, told the press “it is as if nobody cared about me.” In this, María is not alone. Since 2000, as the neoliberal project has advanced, suicide has become increasingly common, particularly among men and the elderly. Following Hurricane María, more than 200 people have taken their lives each year. After the earthquakes began, the number of calls to the suicide hotline rose to 1,600 a day.

Such capitalist internalization has little to do, then, with how influential theorist Byung Chul-Chan’s describes it in Psychopolitics (2017) and other works. For Chul-Chan, collective political action is currently impossible because social networks and the “soft power” of neoliberalism are irresistibly seductive. But for many in Puerto Rico, neoliberalism is not alluring. Instead, it is a violence of such magnitude that, as the reggaeton poet René Pérez once put, it needs to be “spat out.”

Externalizing the disaster has thereby become one of the primary political responses in at least two core ways. First, Puerto Ricans on the islands and in the diaspora affirm that there is “no North without the South.” As was the case in María’s aftermath, communities have mobilized to assist the most affected with greater agility, commitment, and skill than either government. This praxis includes initiatives to raise money or provide direct aid, in areas such as education and health. An example of the latter was the caravan of volunteer truckers and motorcyclists, organized by activists Rey Charlie and Gully Santiago, to provide supplies to those most in need in the southwestern towns of Guánica and Guayanilla. Another instance was the deployment of “Las Clínicas Solidarias,” a group of health professionals, architects, sustainable energy advocates, and grassroots leaders who set up tent clinics to provide free healthcare services to five communities in the southern area.

Although these responses may appear to assume the “self-help” role imposed by capital and the state, Puerto Ricans have not provided aid passively. To the contrary. Frequently called “autogestión” or self-governance practices, they are part of a broader movement. Following the principle of “nos tenemos” (we have each other), this politics deploys bodies, histories, and communal ties to contest the colonial-capitalist project, reconstitute politics, and live otherwise. Consistently, the values of self-governance not only drive the brigades and groups formed in response to a particular situation, but also the work of long-term community organizations such as the G-8 in Caño Martín Peña, Aquí Vive Gente in Puerta de Tierra, and Taller Salud, among many others.

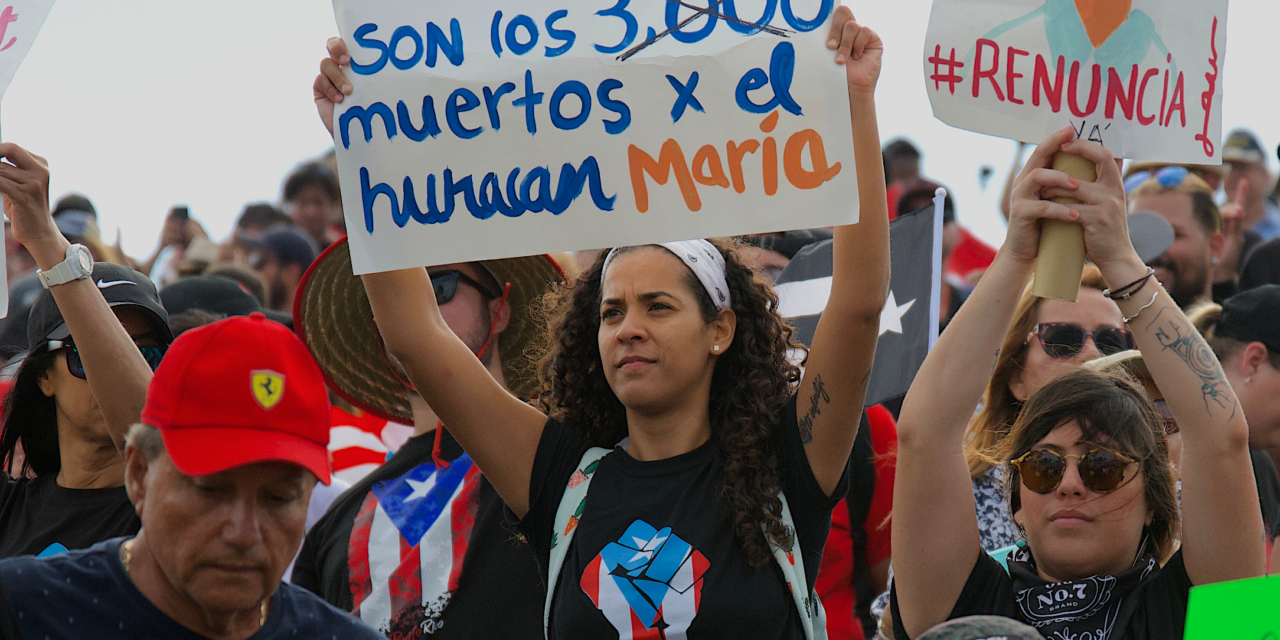

Second, to externalize is also to tell, reveal, and remember. While in earlier junctures even activists have reproduced the discourse of “resilience” promoted by philanthropy and the state, these political actors do not focus on “the poor” or “the needy,” but on those in power who impoverish, intensify suffering, and let die. This was evident in the 2019 summer protests that culminated in the resignation of former Governor Ricardo Rosselló. Responding to denigrating references made by members of Rosselló’s inner circle about María’s dead (“do we not have a corpse to feed our crows?”), thousands of demonstrators used their bodies as mobile canvases and painted tears, blood, and the number 4645 to commemorate those who lost their lives. It was similarly present in a January 22 incident, when a small group interpellated Ricardo Llerandi, the former Chief of Staff under Rosselló, in a café “to the sound of cacerolazos” (banging pots and pans) and the question of “how does it feel to be responsible for letting people die in our country?”

The COVID-19 pandemic then represents novel circumstances but not an entirely new phenomenon. In contrast to prior crisis, the government has moved promptly to adopt potentially life-saving measures such as a curfew. Yet, it did so less to preserve life than to avoid a healthcare infrastructure collapse during an election year and maintain corrupt contracting while communities are on survival mode, and mass protests are challenging to organize. The state’s bottom line is manifest in that it has generally failed to provide safe housing options to people living in the swarm zone, confined with abusive household members, or incarcerated. Moreover, while the government has arrested hundreds of people for violating the curfew, it has an abysmal COVID-19 testing record—an average of 15 per 100,000 people a day—which is the lowest per capita rate of any US state or territory. Equally telling, last April, the authorities purchased $38 million worth of rapid COVID-19 test kits from a small island-based construction company without any expertise in producing medical equipment, but with ties to the party in power. The tests were not only unusable, since they were not FDA approved; they never arrived.

Again, valuing life and each other over state and capital, communities have come together in old and new ways. In Guánica, a group of volunteers called the Community Response Network raised funds to make free tests available, organized a symptom monitoring service, and took to the streets to keep neighbors informed about COVID-19 via megaphone. On April 15, several groups, including the feminist Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, the food distribution network Comedores Sociales, and the anti-debt Jornada: Se Acabaron las Promesas, coordinated a #caravanacombativa, a “drive-through” protest in front of the government television station headquarters. To the chant of “More Tests, Less Corruption,” protesters demanded that governor Wanda Vázquez step up testing, end corporate fraud, promote health rather than arrests, provide reliable information, and allow journalists to attend government briefing sessions. On April 30, activists again staged a protest explicitly named “La Caravana por la Vida.” This time, protesters called for the implementation of policies such as freezing food prices, the opening of school cafeterias, and providing cash and other assistance to assure that no one in Puerto Rico goes hungry. During this demonstration, the police arrested Giovanni Roberto, founder of Comedores Sociales, and predictably (yet ironically) charged him with both violating the curfew and “obstruction of justice.”

Ultimately, even if the governing elites refuse to “learn” from catastrophe, Hurricane María shook both nature and consciousness. The earthquakes unleashed new political aftershocks. And the pandemic confirmed that Puerto Ricans are in a fight for their lives. Undaunted, many grasp that from the overarching attempts for capital and state to privatize all and let die, a more robust sense of community and life can arise. This path will not only be a necessary one for Puerto Rico but also for much of humanity before, during, and after COVID-19.

Frances Negrón-Muntaner is a writer, artist, scholar, curator, and professor at Columbia University. Among her last projects is Valor y Cambio, an ongoing art installation and community currency initiative, valorycambio.org.

Translated from the Spanish by Isabella Lajara, Eunice Rodríguez Ferguson and Frances Negrón-Muntaner