We live in an era in the United States where, in many states, politicians are picking their voters, not the other way around. This is because in most states, the boundaries of congressional districts are in the hands of politicians, and the majority of the party in the state house has more or less carte blanche to manipulated these boundaries as they see fit. In most democracies, this is handled by an independent commission to avoid just this kind of silliness. When left in the hands of politicians, I can see how the temptation to gerrymander is too great to resist. The logic is simple: If we gerrymander the boundaries of congressional districts, we can not only perpetuate our control of the state house, we can also manipulate and control the congressional party from our state, and if others in other states do it, preferably in our political party, then we can control government.

Of course, this is not how it’s supposed to work. And yet, we end up with congressional districts like these two, from California. We tend to hear in the news that Republicans are the ones who gerrymander. But they’re not alone. Democrats do, too. But, without question, Republicans do it more often. Anyway, look at these two congressional districts. One is the 11th District in California, the other is the 38th. One was Republican, one was Democratic. Both images are from c. 2004, and both districts have been re-drawn.

The gerrymander has been used in nearly every democracy, and is one of the many dirty tricks politicians have used to maintain power. That the gerrymander is, by definition, anti-democratic is another matter. The first time the word was used was in the Boston Herald, in March 1812.

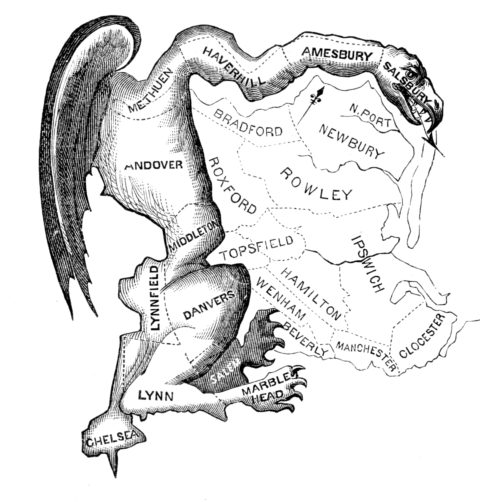

That year, Massachusetts state senate districts had been redrawn at the behest of Governor Eldridge Gerry. Not surprisingly, Gerry’s gerrymander benefited his party, the Democratic-Republicans. The Herald’s editorial cartoonist was not impressed with the re-drawing of the South Essex district:

The Herald charged that the district looked like a mythical salamander, hence we get gerry-mander. It’s worth noting, though, that Gerry’s name wasn’t pronounced ‘Jerry’, but, rather, ‘Geary,’ so, in early 19th century Boston, it was supposed to be pronounced ‘Gearymander’. One theory I’ve read is that the Boston accent re-appropriated the word to ‘Jerrymander.’ More likely, though, something else happened: In the rest of the nascent United States, the name Gerry was likely to be pronounced ‘Jerry,’ not ‘Geary.’ And there we go.

For the remainder of 1812, Federalist newspapers and commentators around the country made use of the term to mock the Democratic-Republican party, which was then in the ascendancy. The Democratic-Republicans were Thomas Jefferson’s party, and it controlled the White House from his election in 1800 until the party split in 1824, largely due to Andrew Jackson. His branch eventually became the Democratic Party we have today. The other branch eventually became the Whigs. Together, the Democrats and Whigs were the core of the Second Party System of the United States, c. 1824-54.

The term also travelled out of the United States, crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the United Kingdom, and north to Canada. To be fair, the coining of the term in March 1812, came on the brink of the outbreak of the War of 1812 in June of that year. So, for the British, this was just another way to mock the Americans. But, either way, the term became an accepted term in the English language by 1847, according to the Oxford English Dictionary.

Source: Matthew Barlow