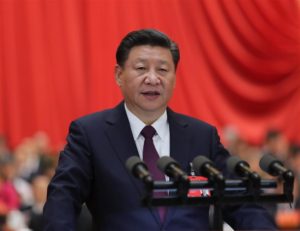

Xi Jinping. Photo courtesy of Xinhua

On October 18, Xi Jinping, the President of the People’s Republic of China, began his second term as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China. Normally, this would also be his last, but as he also introduced a Politburo without a successor, it seemed that he intends to remain for much longer. Xi then announced an ambitious pathway to continue expanding China’s economic development and global prestige.

It was an important moment, and it undoubtedly heralds the kind of change that will trouble pro-democracy activists in Asia and abroad. Predictably, though, the Western press almost immediately made the story about us. At the Guardian, Richard McGregor urged the West to “wake up,” to a China about to steal its birthright. McGregor then marshalled Deng Xiaoping’s words from the 1980s (that China should tread carefully in foreign policy) as evidence that China’s awakening – at the very moment when Western fragility delivers “us” to the brink of collapse – as some kind of long con game. While conspiracy theorists might find such a narrative easy to embrace, it reveals far more about self-perception within (crumbling) Western democracies than it does about China and its global strategies.

I won’t go so far as to say that we are only imagining Xi Jinping’s, the Chinese Communist Party’s, or the People’s Republic of China’s designs on global domination. Xi himself has proclaimed, on multiple occasions, that he envisions a more active role for China in global affairs. In his remarks at the 19th Party Congress earlier this month, he proclaimed that the immediate future “sees China moving closer to centre stage.” Analysts were quick to connect the “centre stage” with Chinese expansion in the Pacific, influence in Africa, and economic weight in the United States. Yet while this might read as a call for Chinese global supremacy, Xi also pointed to less aggressive pursuits: he also argued that China would “[make] greater contributions to mankind.” That phrase should sound far less alarming, because it is really no different than the kind of global altruism that the United States and European Union claim to have practiced for decades.

Even the most militaristic language is part of a rallying cry with a specific historical genealogy. While China was arguably the most powerful country in the world at the end of the eighteenth century, it spent much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries fighting a barrage of European and American incursions. Euro-American powers used force to extract territorial concessions, favorable trading rights, special judicial conditions, resources and labor from China and its subjects. At the same time, those foreign powers used pseudo-scientific racism to exclude Chinese immigrants from their shores, and to put large numbers of Chinese indentured laborers to work in their colonies. Thus, following republican and Communist revolutions in the twentieth century, much of China’s national development and foreign policy have aimed to shake off the mantle of that subordination. Both Xi’s address and the Chinese press reports on the party congress evoked both shameful history and proud recovery.

However, as a scholar of European empire in China, I was struck most profoundly by the way in which Xi looked to the future. The party line is no longer just about recovering from humiliations at the hands of the imperialist West; it is envisioning the opportunity to create a world in which those humiliations seem distant and incomprehensible.

Most of what I have read in the past few days demonstrates a vague awareness of the historical part, but most commentators have overlooked that in favor of more sensationalist stuff. Elizabeth Economy, the director for Asia studies at the Council of Foreign Relations, compared Xi’s rise to a coronation. The New York Times used less loaded language, but twice highlighted Xi’s immense power in pieces that described his many official titles, and that made explicit comparisons to Chairman Mao Zedong. Foreign policy wonks combine a Cold War-era fear of the spread of Communism (we can see this in dog-whistle terms like “Stalinism” and “Leninism”) with a newly manufactured terror at China’s stern rule and recent economic liberalism – in other words, someone else’s exploitative imperialist hyper-capitalism.

Meanwhile, rather than evaluating the possible peaceful overtones of Xi’s insistence that the “struggle” for China’s “dream…will take more than drum beating and gong clanging,” observers focus on what we don’t know. McGregor, who warned us to beware Chinese power, is also the author of a book called The Party: The Secret World of China’s Communist Rulers. His emphasis on the “secretive,” “Leninist” tendencies of the party reinforce some fairly nefarious ideas: that China and the Chinese are inscrutable, that Asian leadership is despotic, and, most pressingly, that we must understand China to defeat it. Although – or perhaps because – the authoritarian-leaning American president seems to find inspiration in the kind of autocracy that has emerged even more forcefully under Xi, both liberals and (traditional) conservatives have embraced the China-as-bogeyman trope.

Alongside the very problematic, racially-tinged ideology that McGregor and others have promoted, the problem with this line of argumentation is that it embraces a type of nationalist social Darwinism that I wish had been put to bed a long time ago. In this conception, which was common in nineteenth-century visions of imperial expansion, China’s strength can only come at the expense of other nations. We have put a reality-show spin on a new Great Game: there can only be one “winner” in geopolitical Survivor. The idea lurks in nearly every recent article on Chinese politics, not far below the surface, and sometimes even at the forefront: if the winner is China, it cannot be the West… and if Western democracies are not Fittest among All Nations, then what do we stand for?

The contours of this problem bring into sharp relief an unpleasant but unavoidable truth about Europe, the United States, and their shared imperialist histories. Western democracies are also empires. In the United States, we have always been an empire. As all of the anxieties about being eclipsed as a global power reveal, our very sense of national and civilizational selfhood is imbued with a global and imperial purpose. Emphasizing China as a problem cloaks our own failures to build just and sustainable societies, but it also reinforces a dangerous imperative: to survive, we must recover a global position that can only be attained through imperial persuasion, coercion, and violence. While Chinese authoritarianism is certainly a problem for many Chinese subjects, our real problem is at home. Western democracies were strongest when they exerted the most force and exploitation, both overseas and at home. Is that really a past to which we want to return?