At the heart of Sean McCann’s critique of The Beauty of a Social Problem are two good questions: “Is there really anything distinctive about an artist who wants her work to be more than just a commodity?” and “do I really need a formally sophisticated work of photography to understand the structural reality of economic inequality?” His answer to both is no; in fact, however, “The Soul of Man under Neoliberalism” seems to me a case study for why the correct answer is yes. Even, or maybe especially, when the question comes equipped with a kind of disclaimer: “The evidence is around me and plain to see if I want to see it.” (Italics not in the original and not mine either, maybe Marx’s?)

We can begin to see the force of the first question (about the commodity) with McCann’s discussion of Kantian formalism. Since Kant is only mentioned three times in the book and each time only in passing, I was at first surprised to see him loom so large. But if McCann is right to say that I “view Hegel more positively,” I think he’s also right to insist on Kant’s relevance. He is, however, much too quick to iron out the tensions in the third Critique. There’s a reason, after all, why Hegel begins his Aesthetics by announcing that he will “exclude the beauty of nature” and one of them is that natural beauty — the “purposiveness of nature” — is so central to Kant and, indeed, that Kant’s central interest is in beauty rather than art. What can convincingly be meant by the “purposiveness of nature” is obviously a big question, which is why I associate Kant with a certain blurriness about the intentional character of works of art, a blurriness that, in the de Manian reading, is turned into a radical refusal of intentionality. And while I have only a spectator’s interest rather than a participant’s stake in the question of how we should finally understand Kant’s position on intentionality,[1] I obviously do want to insist on the absolute centrality of what the artist does (and therefore of the artist’s intention) to our understanding of any work of art. And if that’s enough to make me what McCann calls a formalist, then I’m for sure a formalist.

But so, on my view, is everyone, and not just with respect to art. That is, insofar as the understanding not only of works of art but of all human action involves understanding what some person was doing, formalists – far from repudiating the “fallen world” of “mixed motives” and “personal satisfactions” (as McCann claims Kant does) – are inevitably and more-or-less happily living in it. The word “margarine” on the canonical (William Carlos Williams/Elisabeth Anscombe/John Searle/Jacques Derrida) shopping list means whatever the person who wrote it meant by it even if the person eating the meal might be happier if it had said “butter,” and even also if it’s part of a joke the author always makes and actually means “butter.” Good news or bad, the interests, beliefs and even desires of the reader are irrelevant to the shopping list’s meaning, and this is true of all texts and all works of art – not only Arthur Ou’s photographs but Sebastião Salgado’s.

There’s a difference, however, between this theoretical autonomy (the work means what the artist means by it, regardless of the reader) and an aesthetic interest in autonomy. The aesthetic interest is in works of art that not only mean whatever the artist means by them but are in some sense about the fact that they mean whatever the artist means by them. In other words, they devise ways to foreground the internal relations that structure them. This is what I mean in Beauty when I describe works that are “invested” in or “committed” to their autonomy. It’s this investment in the thing about it that is utterly undetermined by and independent of its beholder that functions as the work’s effort to distinguish itself from the commodity tout court, and it’s certain contemporary strategies for insisting on the irrelevance of the beholder that I characterize as the effort toward both an aesthetics and a politics of indifference.

That’s why when McCann asks whether there’s “anything distinctive about an artist who wants her work to be more than just a commodity,” I think the answer is yes. Indifference to the beholder is definitely not what most social practice artists or any artist interested in the collaboration or participation of the spectator is going for. And, equally obviously, there’s not a single square inch (on either side) of Guatemala,1978 that seeks to do anything other than appeal to the beholder, or that could not (to invoke another of McCann’s imagined points of resistance – the charitable donation) be accompanied by the address to which you should send your contribution. And not only is this repudiation of autonomy characteristic of many photographers, it characterizes much writing about photography. In fact, in his introduction to a recent issue of October, George Baker explicitly links what he calls “an ideological sense of intentionality” with “aesthetic autonomy” in calling out Michael Fried and me (and nonsite.org in general) for supposedly trying “to reinstate artistic… and political values that photography has long helped to overthrow.” Here the very things that function to assert the non-identity of the work and the commodity are decried as sinister anachronisms. So it’s not just that there’s something distinctive about artists trying to make something more than a commodity, there’s even something distinctive about critics encouraging them to do so.[2]

By contrast, look briefly at this picture of another mother and daughter — LaToya Ruby

“Mom Making an Image of Me.” Photo by LaToya Ruby Frazier. (From The Notion of Family)

Frazier’s Mom Making an Image of Me. Where in Guatemala, 1978, the older woman looks down in the direction of the girl and the girl looks out toward us, here, the mirror makes it possible for the two women to look not exactly at each other and not at all at us but at themselves. They face the camera – they’re posing, which, of course, looks like it should be a way of at least acknowledging the beholder if not appealing to him – but they’re posing for the camera instead of for the beholder. That is, the further effect of the mirror, creating what amounts to a room with four walls, is to allow no place for the beholder: no place for the white beholder to experience a demand by the black subject for recognition – these women are looking at themselves, not at us. And no place even for the rich (or anyway richer than the subjects) beholder to experience an appeal for compassion, or even justice.

Which is to say that one of the things this picture is about is the irrelevance of the beholder to the world the picture creates; to understand it (to see it the way it’s meant to be seen), the beholder must understand himself as external to and even excluded from it. And this aesthetics of indifference (the declaration that the meaning of the picture is internal to it) produces the terms of its politics. Frazier is from Braddock, Pennsylvania (where this and the other pictures in The Notion of Family were made), a once prosperous steel town destroyed by deindustrialization. The first work of hers I ever saw was her Campaign for Braddock Hospital (Save Our Community Hospital), 2011. The hospital (which the campaign hadn’t saved) was closed in 2010 by the University of Pittsburgh Medical System, a blow both to health care in Braddock and, since it was the largest employer in the town, to what was left of its economy. Indeed, you get a strong sense of just how devastated Braddock has been when you realize that medical care jobs in general have been among the fastest growing in the country, that the greatest growth is in “Personal care aides” and that now Braddock doesn’t even have those.[3]

Of course, some of the displaced workers from the Braddock hospital got work at the newer UPMC facilities in richer and whiter communities nearby. But here too, the news isn’t all that good. Personal care aide may be the fastest growing job but (like most of the other fastest growing jobs), it’s also among the worst paid, with a median salary of a little over $23,000 a year. So even if you get one of these jobs you’re broke. And most of the people who have them – as you might expect in a world where what McCann calls “racial animus and cultural anxiety” are on the rise – are minority women. It’s facts like this (and the further fact that I think the left shouldn’t care who has to take these terribly paid jobs) that make McCann think that my politics are as “formalist” as my aesthetics because, in arguing that liberal anti-racism plays a crucial role in neoliberal hegemony, I’m ignoring the degree to which “the Republican Party” has become “the party of white nationalism and sexual conservativism.”

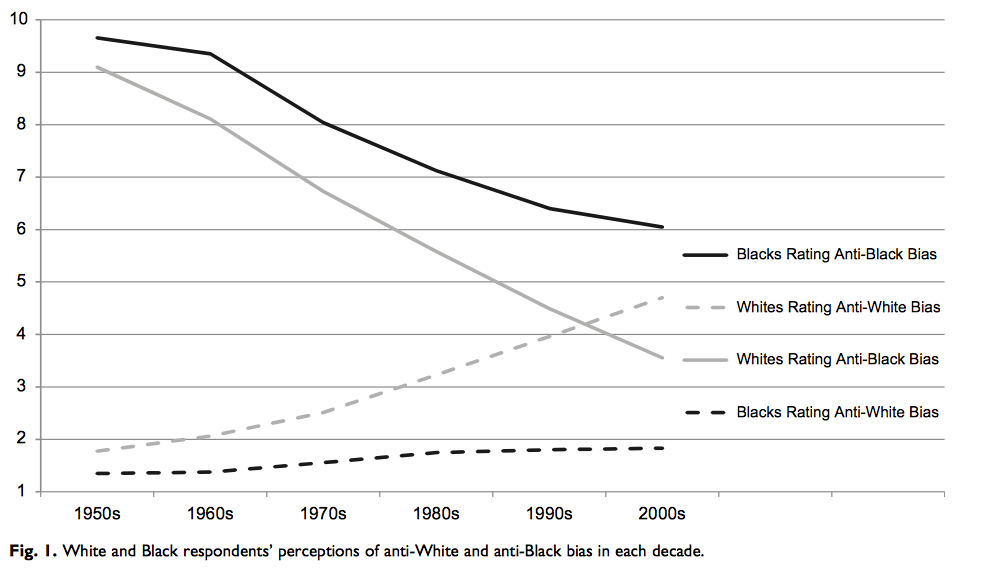

But actually you can’t begin to understand the Republican party today without understanding the contribution made to what he calls its “toxic brew of cultural resentment” by the hegemonic power of anti-racism. Today, a majority of every racial group in America understand themselves as victims of some discrimination, and 26% of white people even understand whites to be the group that faces the most discrimination. Furthermore, if you focus not just on white people but on Republicans, that number goes up to 41%. And if you just do Trump supporters, it’s 45%. 45% of Trump supporters have the (deeply delusional!) view that they are the greatest victims of discrimination in the U.S. today.[4]

This vision of whites as the victims of discrimination or of “bias” is a relatively recent one. Didier Eribon, reporting on what he calls the French working class’s turn from the left to the right describes the emergence of complaints like “They’re getting all the welfare payments and leaving nothing for us”[5] and, of course, Americans can remember Reagan’s welfare queens, and can today hear complaints like the one reported as characteristic of Trump supporters who see themselves as victims: “if you want any help from the government, if you’re white, you don’t get it. If you’re black you get it.”[6] Contemporary white racism – racism as anti-racism — is an artifact of the welfare state and, especially in the U.S., of its decline.

As the graph above suggests,[7] it seems to have been only in the late 60s and early 70s, that whites began to think of themselves as the victims of discrimination, a rise that coincides both with the Civil Rights movement and what we now know was the beginning also of an extraordinary rise in economic inequality, one that has overwhelmingly benefitted the top 1% (who now have 39% of American wealth), less overwhelmingly benefitted the next 9% (who also have 39%) and left everyone else far behind: 90% of the population has 23% of the wealth.[8]

Most of that 90% is white. And if it’s true (as it appears to be) that Trump did best neither with rich people nor with very poor people (Clinton killed him among those making more than $120,000 a year and less than $30,000) but with everyone in between, then working and middle class white people, seeing themselves fall farther behind the upper class and (mistakenly) blaming not capitalism but racism, are his base.[9] This is, in effect, what Barbara and Karen Fields predicted when they worried about the consequences of a “vocabulary” that, identifying injustice with “discrimination,” leaves no room for any other kind of “unfairness” and no room in particular for the reason those health care aides are paid $23,100 – which is not the racism of the employers but their need to pay workers less than the value of what their labor produces.[10]

This is why the “is it economic anxiety or is it racial resentment?” debate over why people voted for Trump is itself an ideological artifact. The anti-racist left is angry because minority women are the ones being forced into those bad jobs; the anti-racist white right is angry because they’re afraid they’ll be forced into those bad jobs themselves. But – and this is the point of a politics of indifference — why should the left care who has to take the bad jobs? Or, more precisely, why should the left be committed to a program of social justice that seeks to guarantee everybody an equal opportunity to get a good job rather than one that seeks to make all jobs into good ones?

McCann complains that I take neoliberal encomia to market efficiency too seriously. But those encomia – the differences between bad inequalities (based on race, sex, etc.) and good ones (based on ability, hard work, etc.) are built into the very structure of an anti-discrimination that seeks to hold neoliberalism to its market-based meritocratic promises. My point is not that capital always or even usually lives up to those promises; it’s that we shouldn’t turn the job of the left into trying to make sure that it does. Which, once you redescribe a preference for socialist redistribution of wealth over liberal redistribution of skin colors as a refusal of this “fallen world” (“fallen” is post-lapsarian for “There is no alternative”), is exactly what you’ve done.

So when McCann asks if we really need “a formally sophisticated work of photography to understand the structural reality of economic inequality?” my answer is that we apparently need something because all that carrying on about the “toxic brew of cultural resentment” seems to have made it pretty invisible. And in fact, what we need is exactly that formal sophistication. Why? Because that sophistication consists in converting the photograph’s external relations – its indexical tie to its subject, its appeal to the beholder – into internal relations (like those between the “black blotches” and the sculptural objects in the Arthur Ou photographs). And it’s that transformation that makes visible the difference between the way we see inequality and its “structural reality.” Asserting the autonomy of the art work’s structure both from the world it indexes and the response it produces, photographs like the ones I write about not only exemplify but allegorize the experience of structure itself – and the irrelevance to it of who we are.

And they do so in a period when both neoliteral art and neoliberal politics insist on that relevance. In other words, if you think about inequality as a function of racism and sexism (even when you call that racism and sexism structural), you understand inequality as essentially connected to how we feel about and so how we treat each other – that’s why, for example, someone like Ta-Nehisi Coates can plausibly describe the wealth gap between blacks and whites as the best evidence of white Americans treating black people as “sub-humans.”[11] But the difference between capital and labor is not a function of how we feel about each other; white people can learn not to treat black people as inferior (the whole project of anti-racism consists of nothing but the effort to get us to do exactly that); capital cannot learn how to stop exploiting labor. To make a profit, health care employers must pay health care employees less than the value of their labor; if all the personal care aides were white men, they’d still be making $23,000 a year.

McCann says that arguments like that are really not political – that they’re an “ethical stance,” a demonstration of a “stern commitment to higher principles and of distaste for shallow sentiment.” But he doesn’t say why (or even exactly whether) he disagrees with them. Rather he redescribes efforts to show that anti-discrimination is not just compatible with inequality but today functions as a defense of it (which is why Adolph Reed and I call the politics of identity a class politics) as an expression of my sense that “personal feelings about bias or unfairness” are “trivial.” And, more generally, “The Soul of Man” relies heavily both on this strategy (painting a portrait instead of countering an argument) and on the particular character of the portrait: my “stern commitment to higher principles,” my general preference for the “higher” over the “lower” and for resisting “the temptation to pity and sorrow.” But, just to take the last example, insofar as I do say something in praise of resisting the temptation to sorrow and pity, it’s not an argument against feeling the most powerful emotions about, say, your grandparent who died in the camps; it’s an argument against making powerful emotions about the camps the center of your politics or your art. I say that the commitment to affect and identification functions in the service of a left neoliberalism; McCann says that my critique of affect and identification is “stern.” How is what he says a response to what I say?[12]

Maybe his core objection here is that, despite my anti-identitarianism, my own views are in fact the expression of an identity? This is what’s suggested by his description of my idea that “formally sophisticated art” can help us see the difference between structural inequality and “cultural anxiety” as a “badge of identity.” And by the specificity he gives that identity when he remarks that, in addition to anti-discrimination, one of the many things that are compatible with increased economic inequality “is a taste for fine art.”

Of course, “formally sophisticated” and “fine” are not exactly the same, and fine art is not what I’m arguing for in The Beauty of a Social Problem; you can go to the same galleries and the same museums that show the work I’m talking about and find lots of photographs that do just the opposite of what I’m describing. Also, a “taste” for it is not only compatible with economic inequality, it’s probably dependent on it — which is part of the argument I make about Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: that Evans’s photographs, precisely in their ambition to establish themselves as art, declare their unavailability to their subjects, and therefore function not simply as pictures made possible by the class structure (fine art) but as pictures of it (formally sophisticated art). But, and this would be the point of the sociological category of a taste for fine art rather than the aesthetic category of a taste for good art, it’s true that any time you put on the little badge they give you when you pay your way into the museum, whether it’s the fine or the formally sophisticated you’re looking for, you are indeed putting on a badge of identity.

You’re not, however, putting on what Du Bois called “a badge of color.” Du Bois uses that term in Dusk of Dawn, a text that is, on the one hand, deeply skeptical about what today would be called the value of diversity (what good is it, he asks, to “dissolve” the “color line” into “a class line between employers and employees” and thus expose “black labor” to “an exploiting capitalist class of their own people”) but, on the other hand, is just as deeply committed to the promise of a black elite (not the rich but “the best, most courageous, most expert and scholarly leadership.”[13]) It was their job, Du Bois thought, to lead their people into the world that would be created after what seemed to him (in 1940) the imminent “collapse of capitalism.”

Obviously that didn’t work out; not only did capitalism hang on but black scholarly leadership has been more or less indistinguishable from white scholarly leadership in its contribution to producing exactly the kind of class stratification that Du Bois opposed. But, in his skepticism about the value of trying to create “a Negro capitalist class which will exploit both Negro and white labor,” Du Bois did get at the difference between a badge of color and a badge of class, a difference that gets elided every time someone says, “But class is an identity too.” Color is an ascriptive identity – it’s the badge that makes you black or Latinx, and 70% of personal care aides wear it, along with the badge of sex which makes them victims of another kind of discrimination. Rectifying the injury done to them as women of color requires us to take note of these badges and to begin to see the people who wear them differently — to see the badge as a mark not of inferiority but of difference and to dismantle the obstacles they face because of it.

But personal care aides also wear the badge of class and, assuming with McCann that they don’t have much taste for “fine art,” it’s the badge not of their visit to the Art Institute but of their membership in a particularly exposed fraction of the working class, subject to a more oppressive exploitation than other more fortunate members of the working class. I say more fortunate rather than more skilled or more educated because, as the ongoing adjunctification of the professoriat suggests, skills and education are in themselves no guarantee against the threat of further proletarianization. And, of course, the adjunct professor who makes barely more (and sometimes less) than the personal care aide may be a white man and have a taste for fine art more refined than mine or McCann’s and be no less an exploited member of the working class for that. So you can take the badge off or you can put it on, it’s only your relation to the means of production and your ability to make yourself useful to those who own them that matters.

What our white male adjunct professor has in common with our black female personal care aide is not an identity but a class position. To see the structure of inequality is to see that. Formally sophisticated (as opposed to fine) art can help you because it can help you see the difference between your identity and your class. But there are other, no doubt more efficient ways. Sometimes, maybe, joining a union? Unfortunately that’s an opportunity sometimes rejected by the segment of the working class that reads journals like Politics/Letters and increasingly denied even to those of us who don’t reject it. So maybe formally sophisticated art is a way to go. Although, as I acknowledge and Sean McCann’s essay demonstrates, it doesn’t always work.

***

[1] And no stake at all in de Man being right about Kant. Robert Pippin (private communication) suggests that Kant is driven toward the exemplary status of natural beauty because his picture of intention is restricted to “a concept/rule imposed on sensible material” and so he can’t quite see how “the conceptual stakes in a work’s meaning can be present in an affective-sensible modality,” a suggestion I find extremely helpful.

[2] Unless, of course, you just treat “more than a commodity” as an honorific. And it’s true that McCann seems sometimes to be doing just this, as when he suggests that my problem is with the “vulgarity of the market place.” But it’s hard to believe that anyone who has ever, say, read The Golden Bowl (as I’ll bet McCann has) can think vulgarity is the issue. James is pretty clear that refinement is the more insidious market value.

[3] Food preparation (“including fast food,” median pay $20,180) is second, registered nurses third and home health aides fourth. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/most-new-jobs.htm

[4]http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2017/08/trump_s_bigoted_base_by_the_numbers.html

[5] Didier Eribon, Returning to Reims, translated by Michael Lucey (Los Angeles, 2013), 142. Returning to Reims vividly describes a certain segment of the French working class while unfortunately and even more vividly it redescribes the problem of class as the problem of classism.

[6] https://www.npr.org/2017/10/24/559604836/majority-of-white-americans-think-theyre-discriminated-against This particular sense of victimization is why it makes more sense to think of contemporary right populism as a form of neoliberalism than as a reaction against it – the grievance against capitalism finds expression as a grievance against racism.

[7] http://www.people.hbs.edu/mnorton/norton%20sommers.pdf

[8] https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/a-guide-to-statistics-on-historical-trends-in-income-inequality

[9] Which is not to say that all of Trump’s working class support involved racism. Morgan and Lee’s analysis shows that 12.7% of 2012 Obama voters voted for Trump; maybe their racism was late-blooming? More generally, they show “that approximately 28 percent of Trump’s 2016 voters were Obama voters in 2012 or nonvoters in 2012. In comparison, only about 16 percent of Clinton’s voters were Romney voters in 2012 or nonvoters in 2012. The Obama-to-Trump voters were disproportionately white and working class, whereas the 2012 nonvoters who voted in 2016 were disproportionately white.” https://www.sociologicalscience.com/download/vol-5/april/SocSci_v5_234to245.pdf

[10] Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields, Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life (London: Verso, 2014), 287. Case in point: UMPC reported a net income of $1.3 billion in 2017 and continues to hold its own in competition with Highmark Health, which itself reported “an excess of revenue over expenses of $1.1 billion.” http://www.healthleadersmedia.com/finance/pennsylvania-players-highmark-and-upmc-continue-battle

[11] For a more extended discussion of these issues see the articles collected in https://nonsite.org/issues/issue-23-naturalizing-class-relations

[12] With respect to the accuracy of the portrait, I confess I don’t see myself as very (or even a little) stern. But no doubt I’m not the best judge. McCann totally gets me, however, when he speaks of my “disdain” for ethical kitsch, for people basking in their own disapproval of “the Holocaust, of slavery, of all the genocides.” But then, chastising me for taking at least as much pleasure (and I do!) in disapproving of identity politics, relational aesthetics, etc. he misses the point. If there weren’t some pleasure in opposing widely held positions, intellectual life would be a lot less fun. The ethical kitsch is in proudly proclaiming our unalterable hatred of something everybody already hates.

[13] W.E.B. Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn (New York, 1986), 706, 715.