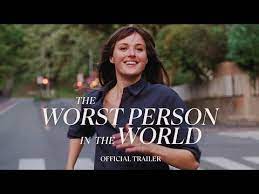

Throw a Tampon at your Dad – The Worst Person in the World is Joachim Trier’s best movie yet

Matilde Augusta

Joachim Trier’s The Worst Person in the World is interested in gender in a way that the other movies in his Oslo trilogy are not. In fact, it seems as though Trier is trying to confront a possibly sexist legacy. Both Reprise (2008) and Oslo, August 31st (2011) were made well before #MeToo. The Worst Person in the World, however, is very conscious of being a post-#MeToo movie, with one of its twelve chapter titles explicitly referencing the movement. There is also a scene where the protagonist Julie (Renate Reinsve), a woman in her early thirties who struggles to find out what she wants to do with her life, sees her ex Aksel (Anders Danielsen Lie) debate a feminist during a national broadcast.

Julie is running on a treadmill at her gym when Aksel appears on one of the TVs. She immediately tunes into the broadcast, where Aksel defends his comic legacy against a feminist attack. Aksel is a 40-something who has made a name for himself on the underground scene in Oslo with a comic called Bobcat. He comes from more or less the same world as Lie’s other roles in the trilogy. He is a central figure in Oslo’s underground/art scene, a creative and presumably from the city’s wealthy West Side. Aksel feels like an older version of Philip (also played by Lie) in Reprise, a tortured young writer who experiences psychosis due to falling in love with Kari (Viktoria Winge).

In The Worst Person in the World, the feminist objects to Aksel’s general political incorrectness and the depictions of women in his cartoons [?] (which recalls one of the first things we learn about Aksel, namely that Julie remembers seeing a vaguely sexist cartoon of his at one time). Aksel’s defense is pretty standard, that art should not be a safe space and so on. He is not concerned about whether someone might be hurt by his depictions of taboo topics such as incest.

It is difficult to watch this scene and not think of it as in conversation with the legacy of Trier’s past Oslo movies. Not only is Aksel’s defense similar to one we might imagine from the director in response to accusations of sexism. There are also several through-lines between the earlier parts of the trilogy and its culmination that emphasize a confrontation with the legacy of the earlier Oslo movies. Actors Anders Danielsen Lie and Hans Olav Brenner appear in all three films. Every part of the trilogy happens in more or less the same social sphere, and certain things are repeated. Lie’s characters are always hospitalized. In Reprise, Philip ends up in a psychiatric hospital after falling prey to psychosis. In Oslo, August 31st, heroin addiction lands Anders in rehab. In the last part of the trilogy, his character is hospitalized for a physical illness.

The broadcast debate scene specifically made me recall a moment I vaguely remembered from Reprise. Reprise is centered on Philip and Erik (Espen Klouman Høiner), who have been friends since childhood and are aspiring novelists. They are part of a larger all-male friend group with ties to the punk scene. The friend group is confronted with their inability to let their guard down and be real when Philip is admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Lars (Christian Rubeck), a medical student and one of the members of the group, makes what has to be the longest misogynist speech in Norwegian film history. He begins: “Girls just aren’t cool. They can be pretty and cute, maybe even sexy with some constructive dieting. And if you’re lucky, they’re also nice and kind. Dumb but kind. But who wants nice?” and goes on like that with increasing misogyny for something like another 45 seconds.

Of course, you can have a sexist character who delivers a misogynist speech in a book or movie without the book or movie itself being sexist. A movie with good politics need not be a manifesto. Yet this case is not straightforward. Lars gets no pushback from the other guys, and in this sense, there is nothing dialogic going on. Johanne (Rebekka Karijord), an employee at the publisher that publishes Erik’s debut novel, is the only one who confronts the boys about their unflattering and politically dubious ways during a chance encounter at the beach. When I rewatched this encounter, I felt like Johanne was being mocked and looked bad. Yet in a sense she does get the final word. Reprise ends with what Erik imagines as the end, not an actual ending. In this fantasy, Johanne marries Henning (Henrik Elvestad), the guy she gets into an argument with at the beach. He has a change of heart and has become a politically correct leftist by the time his first novel comes out. Lars, the misogynist, is also in a happy relationship with a woman at the movie’s end and appears to have changed his ways. The guys of the friend group are structurally put in their place, even if the woman characters are unsatisfying and flat and misogynist nonsense goes unchallenged.

I first watched Reprise in high school after a friend told me she thought she had seen me in it. And sure enough, for a second or two, six-year-old me appears on the screen as I’m walking in the children’s parade that always happens on May 17th, Norway’s constitution day. Trier must have bought this footage from the state TV channel or something. I did not think of it as a particularly sexist movie, even though a part of Lars’ misogynist speech hit close to home and would haunt me for the next few years. Lars says that girls don’t know about cool music or literature. If they know about anything cool, it is because their ex, brother or father showed it to them. A male friend had introduced me to several of my favorite bands. I desperately craved the approval of older guys like the friend group in Reprise and knowing that this might be what they really thought of me hurt.

The fact that I, at sixteen, could kind of believe what Lars was saying, or otherwise did not yet have the adequate language to counter his nonsense, makes me think that there is a risk to including this kind of speech in a movie without any retribution or dialogical response. I’m sure I believed that Lars was a horrible person. But his words did not register as blatant misogyny to me since I was not yet too familiar with feminism.

It is not difficult to imagine Trier in a similar position to Aksel on the broadcast if someone were to confront him about the inclusion of this speech and his unsatisfying woman character. Like Aksel, he might say this or that about free speech and darkness in art. Norwegian critics and academics have at times found sexism in his movies. For instance, in a 2010 article, Oda Bahr writes about how boring she finds the superficial depictions of women in Reprise. She calls for more interesting parts for women than the emotional victim portrayed by Kari and the mocked publishing woman conceived through Johanne.

I’m not convinced that Trier deserves a takedown like Aksel, not that anyone necessarily does. Is he trying to preemptively avoid that with this movie? Or is it a sincere attempt to try and reckon with something he feels did not go right in Reprise?

A lot has changed by the time we get to The Worst Person in the World. Julie is a complete character. Reinsve’s acting is phenomenal (so much so that she earned the Cannes Film Festival Award for best actress). It is also clear that much more thought has been given to her interiority than certain central women characters in the Trier canon. The contrast to Kari, a shy girl from the East Side who is part of the punk scene, and Philip’s love interest in Reprise, could not be more prominent. Kari feels more like a paper doll than a person, which is a fault of the script and not her acting.

Julie’s explanations that she prefers a flaccid penis because then she is the one who makes it hard have very little in common with the speeches of the women of Reprise and Oslo, August 31st. Even the less demure women in these movies, such as Johanne in Reprise and Mirjam in Oslo August, 31st run the risk of feeling like stock or flat characters because their problems feel so much like the generic, all-purpose take on women’s problems as men would imagine them. For example, Mirjam notes how hard she finds aging and that her male friends are dating increasingly younger women. Kjærsti Odden Skjeldal, who plays Mirjam, was 33 when the movie came out in 2011. A generous viewing might say that Trier understands the horror of the state of things, where a woman in her early 30s is considered washed up. But from my recollection, it felt more like a lament about a natural law than a societal critique.

It is not always easy to know what to make of Trier’s women. At best, the women in Reprise are there to evidence the men’s bad behavior. Whether they serve this purpose, reflecting the problems with these men symptomatically rather than critically, is another question. At worst, they are there to evidence Lars’ ideology.

The Worst Person in the World does not leave much room for this kind of ambivalence because the women are not merely there to say something about the men. A welcome result is that the movie’s gender politics become much clearer and much better. In the movie’s third chapter, titled “Oral Sex in the Age of #MeToo,” Julie writes an article with the same title. The article appears to express ambivalence about giving oral sex in a way that might be comparable to recent feminist critiques by Amia Srinivasan and others. Like Srinivasan, we feel that Julie is skeptical of the all too liberal sex positivity but not ready to wholeheartedly embrace the potentially authoritarian teachings of the anti-porn feminists. The movie at large might share this position.

This is just one of many scenes when the movie centers on discourse about gender and sex. In the first chapter, “The Others,” there is a priceless moment when one of Aksel’s friends mansplains mansplaining to Julie. From the get-go, viewers familiar with the rest of the trilogy learn that we are in a very different universe than the male ego-powered Reprise and Oslo, August 31st. A speech like the one Lars delivers in Reprise is unthinkable in The Worst Person in the World.

This full realization of the women characters is also why The Worst Person in the World is Trier’s best movie yet. The incredible and painful scenes between Julie and Aksel would not have been possible between Philip and Kari; Kari is mainly a prop for Philip. Julie feels so real that I would not be surprised if I ran into her the next time I browse the shelves at the book store Norli in Universitetsgata, where she works in the movie.

Trier also proves himself as a visionary director in this movie. Psychedelic trip scenes in movies are like dream scenes in novels: nine out of ten times they are a mistake. But Trier manages to pull one off. This is true even though his mushroom-powered sequence has all the hallmarks of an insufferable trip scene. There is the on-the-nose imagery, such as the iconic moment when Julie hallucinates her father and throws a used tampon on him. Then there is the exaggerated weirdness that tries to be deep in an acid-head kind of way, like when Julie’s body ages by several decades and she nurses a baby with her aged breasts. Not to mention the blatant references to the DMT trip scene in The Big Lebowski, in which a high Julie falls onto a Persian rug that, you might say, really tied the room together. Like that scene, the trip scene in Trier’s movie adds more than it takes away.

Overall, there was just one thing that could have been a lot better. Trier seems to write for a North American audience when he makes a crack about a character reclaiming her Sámi identity after taking a DNA test to find out that she is 3% Sámi. This is played for an easy laugh, but it does not reflect the reclamation of Sámi identity in Norway. Membership on the electoral roll of the Sámi Parliament (the only official marking of Sámi identity) is based on having ancestors who spoke the language. You need to have had at least one great-grandparent whose mother tongue was Sámi to join. Because of two centuries of assimilation, many reclaim their Sámi identity as adults, and therefore, this model is better suited than blood quantum. Sámi people who came to the community as adults in good-faith efforts to keep the culture alive might find this subplot quite hurtful.

The strangest thing about watching The Worst Person in the World was that the experience was pretty similar to Scorsese’s The Irishman in the sense that it felt like it was trying to signal the end of something. It marks the end of the Oslo trilogy, that is true. But at 47, Joachim Trier is most likely far from both death and the end of his career.