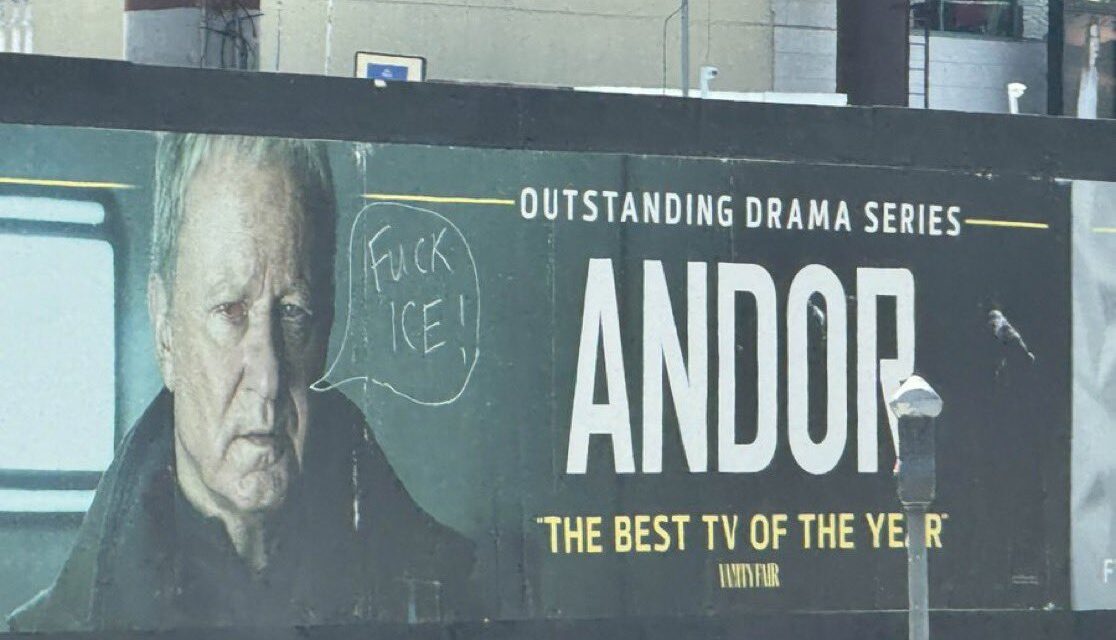

Caption: A billboard advertisement for Andor in Los Angeles, CA featuring Luthen Rael (played by Stellan Skarsgård), with a dialog bubble reading “Fuck ICE!” graffitied on.

Credit: David Ridker (@DavidRidker on X.com)

“And then remember this: the Imperial need for control is so desperate because it is so unnatural. Tyranny requires constant effort. It breaks, it leaks. Authority is brittle. Oppression is the mask of fear.” – from Karis Nemik’s manifesto in Andor

Halfway through the first season of Andor, a young revolutionary named Karis Nemik

pens a manifesto, completed on the eve of his death. After being crushed by a slab of credits (the Empire’s hard currency) at the end of a heist to steal the quarterly payroll of an Imperial sector, and plotting an escape route for the heist team, Nemik insists on his deathbed the manifesto should go to the show’s titular protagonist Cassian Andor—at this stage in the series, a hired gun skeptical that there is any hope for resistance against the Empire at all. At the episode’s end, Cassian leaves the revolutionaries behind and takes his cut, escaping and hiding out at a far corner of the galaxy. It is only after being incarcerated and breaking free from a labor camp, learning of his adoptive mother’s death, and the Imperial occupation of his home planet that Cassian finally listens to the manifesto in full. Nemik’s words are not heard again until the show’s finale, when Lio Partagaz, the head of the Imperial Security Bureau (the Galactic Empire’s spy agency), listens to a recording of the manifesto before committing suicide in response to his failure to contain classified information about the empire’s secret planet-destroying superweapon, the Death Star. In the face of his failure, he mutters: “… Just keeps spreading, doesn’t it?” The viewer realizes that, in the gap between these two scenes, the concept of revolution has been transformed from fanciful and idealistic to a wildfire: uncontainable, irresistible, and inevitable.

In that gap the show covers five years of galactic history, a gap in which the emergence of the Rebellion as an institution is traced in great detail, across multiple sites of struggle from the floors of the Galactic Senate to the fractured communities of the galaxy’s outer rim. The return of Nemik’s manifesto illustrates, alongside the expansion of a revolutionary militia, that the unplanned, untracked spread of a revolutionary ideology has produced a galaxy in which revolt is a seeming inevitability. Throughout the show, there has been an interplay between spontaneity and structure, revolutionary vanguardism and anarchic momentum. By the series’ end, both come into view as deeply necessary for the set of conditions which allow the possibility of success for the events of the franchise’s original trilogy of films—stories that are so engrained within popular culture that they approach the realm of contemporary myth. We might return to the scene of Nemik’s death, then, as the intersection of the ideological and financial birth of the Rebellion—a point of origin that re-situates and recontextualizes George Lucas’ anti-imperialist children’s fable and the mass media franchise it has spawned for our present cultural and political moment.

The Galactic Empire that Nemik attempted to theorize and resist was, within the series’ timeline, about 14 years old at the time of his death. Within our galaxy, our time, our world, that fictional empire has existed in the cultural realm for nearly half a century. It has produced a set of aesthetics integral to an intellectual property that has been as much a signal of U.S. cultural hegemony as any other. Star Wars, as a franchise, exists as a global commodity and cultural export, one which has mined Imperial iconography for t-shirts, action figures, LEGO sets, and children’s costumes for decades. If there is anything Andor might do to (re)shape or question contemporary popular culture, it is perhaps to give us pause at how strange it is for children to dress as interstellar fascists for fun. It is, however, the expansive nature of Star Wars as a cultural artifact, expanded universe, and property of the Walt Disney Company after its purchase of Lucasfilm in 2012 that allows the $645 million show to exist at all.1Caroline Reid, “Disney Reveals $645 Million Spending On Star Wars Show ‘Andor’,” Forbes, Dec 22, 2024. Disney’s tenure ushering the franchise back to life in the 2010’s and 2020’s has been critically contentious, to say the least, but it is now undeniable that Andor, against all odds, is an artistic triumph in the midst of a bloated media landscape of self-cannibalizing franchises. That is even stranger because of the fact that Andor is, without question, in the thick of this cultural phenomenon: it is a prequel to a prequel (2016’s Rogue One: A Star Wars Story), and a sequel chronologically to George Lucas’s “prequel trilogy” of the early 2000’s. And yet, by treating this strange and expansive universe originally crafted in the 1970’s deeply seriously—as, in a sense, history—Tony Gilroy’s show has effectively provided a bridge between our world and that of the struggle to resist a seemingly hegemonic empire in a galaxy far, far away. Revolution becomes at once timeless, deeply immediate, and necessary. After Andor, one cannot refuse to grapple with the fact that Star Wars is, and always has been, a tale of U.S. Empire. It has a role in how those of us today—not simply as consumers of media, but as historical actors within the core of an empire in decline—must rise to meet our historical moment as the “imperial boomerang” as described by Aimé Césaire comes home to roost in the shape of what is undeniably the (perhaps new, arguably not so new) fascist turn within the U.S.’ domestic sphere.2Aimé Césaire, Discourse on Colonialism, trans. Joan Pinkham (Monthly Review Press, 2000), 35-46.

Andor makes apparent what is arguably true, or at least possible as a ground of analysis, for much of the contemporary landscape of popular culture: that the self-cannibalization of science-fiction and genre franchises whose source texts emerged largely from post-World War II U.S. literature and cinema creates a cross-temporal relationship between the present and the rise of the U.S. as a technocratic empire at the global scale. It is impossible to watch Andor—in which senators are arrested for political speech, and naming genocide on a senate floor is career-ending—as detached from our contemporary moment. Essential to understanding these parallels is Andor’s role in re-contextualizing or perhaps re-focusing viewers toward what Star Wars was at its origins, and what it has become in its transformation from a single film into a resource for an expansive mass media franchise in a globalized capitalist economy. It is precisely because the original Star Wars was responding to the historical, cultural, and political forces of its time—namely, the U.S.’s devastating intervention as an imperialist power in Vietnam—that Andor feels prescient. That is not because of some imagined foresight or deep commitments on behalf of Andor’s writers (who penned Season 2’s scripts long before Israel’s U.S.-backed genocide in Gaza began), but simply because the source text of the universe the show was engaging with was reacting to the same historical contradictions that have moved forward in time, alongside the evolution of the Star Wars franchise itself, to produce our present.

From this perspective, the simultaneity of the Rebellion’s ideological origins and financial origins takes on extra weight. Nemik is quite literally crushed to death beneath the very same wealth that ultimately makes possible the destruction of the Death Star by the Rebellion—an event which takes place both five years in the franchise’s future and 45 years in our own cultural past. Because of this, the anticipated viewer comes to the show knowing the Rebellion’s existence and its success as an inevitability. That Nemik is considered by Cassian and others in the heist team as a naïve idealist thus creates a schism between viewers (outside) and characters (inside): what the viewer knows to be future fact is positioned as an almost complete impossibility—the act of faith to leap into a rebellion almost certain to fail, then, is made visible to the viewer from the start as an inevitability. Similarly, our entrance into this story is through Cassian as a mercenary, quite far from the rebel who will sacrifice his life for the rebellion in five years’ time during the events of Rogue One. Over the course of the three-episode arc that depicts the heist, seen both from the perspectives of the proto-revolutionaries and the imperial bureaucrats attempting to trace their movements, we begin to see the scope of possibility shift—not easily, not quickly, in fact quite painfully, amidst grounded pain and sacrifice. And those shifts are, largely, the product of the movement of capital: Luthen Rael—who organizes the heist while attempting to produce a coordinated network out of disparate revolutionary groups—uses a monetary incentive as bait while also attempting to radicalize Cassian along the way. “Don’t you want to fight these bastards for real?” he asks Cassian, illuminating the task gap that must be crossed for Andor to grow to become the revolutionary we know him to become, and perhaps also asking us as audience members to re-orient ourselves to the magnitude of what it means to fight for real against an empire capable of wielding weapons of destruction at the edge of our imaginative capacities.

In the timeline of our own world, there is a three-year gap between the first appearance of Nemik’s manifesto in Season 1, released in 2022, and its return at the end of Season 2, released in 2025. In that gap, the political, economic, and moral frailty of U.S. hegemony has become harder to obscure while its military hegemony maintains an effective monopoly at the geopolitical scale. Though we are still less than a full year into Donald Trump’s second presidency, the tension between these two facts is likely to be one of the defining contradictions of the decline of American empire. The ongoing genocide in Gaza—enacted by Israel, supported by U.S. weapons and with political backing across both the Biden and Trump administrations—has rendered any moral legitimacy for unipolar American hegemony obsolete. The inability (thus far) for the political tools at the disposal of the global majority to meaningfully stop the indiscriminate bombing of civilians and use of mass starvation—whether that be through international law and the United Nations, grassroots movements by students and organizers across the globe, calls to stop weapons shipments by trade unions, and more—has produced a crisis for the project of (neo)liberalism: there is a starkly clear injustice that we are complicit in, and even if the bombing does stop, no one can stop the knowledge of complicity in injustice. One cannot watch Andor in 2025 and reasonably imagine, as some imagined when they watched the original Star Wars, that the United States was the Rebellion.

While the schism produced in Season 1 relies on the tension between the audience’s knowledge of the Rebels’ success and the complete dismissal of Nemik’s idealism by Cassian and others within the world of the narrative, its reappearance in Season 2 almost inverts this dynamic: narratively, the fallibility of Empire is abundantly clear as the last hours of Andor witness the collapse of imperial bureaucracy against the now fully developed, intricate, flawed organization that is the Rebellion. And yet for the average viewer in the U.S., there are more and more constraints on our modes of living than ever: the National Guard marches the streets of the capital, political speech is under scrutiny to a degree not seen since the McCarthy era, and any critique of U.S. support for Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza is now grounds for censure by most employers and universities. The revolutionary fable to which Andor ostensibly is a prequel feels both less convincing and more necessary. The distinct lack of a grounded, material, organized, and sustained infrastructure for anti-fascist and anti-imperialist resistance within the U.S. is sorely felt—perhaps most of all by those who are committed to the task of attempting to build such a movement. What appears as inevitable within the world of the show feels ever more distant within our own lives. We know what happens in the Star Wars universe after Andor, but now feel closer to the Cassian of season 1: attempting to find solid ground on the terrain of fascism’s squeeze, skeptical of the efficacy of revolutionary hope, tempted to cash out and find somewhere safe while we still can.

While the show itself has traced the consequences of the emergence of the Rebellion as an infrastructure—the economics, politics, and organizational structures that have allowed it to become a meaningful force—the return of Nemik’s manifesto serves as a reminder of the off-screen afterlife of an ideology of resistance that has also made its way across the galaxy. The impact of this appears throughout the show as well, with small moments such as a hotel porter whispering to Cassian that “rebellions are built on hope,” a phrase that carries through Rogue One to become a catchphrase of the rebellion. It is meaningful that Nemik’s words spread without coordinated propaganda—there is no side plot in which the manifesto is planted or distributed to produce revolutionary potential. But it is simultaneously the institution of the rebellion—something we see built with money, blood, and meaningful sacrifice, including sacrifices of moral purity—that allows the spread of ideas to take root and find direction. The ground-eye view of rebellion produces an acknowledgement that the myth of Star Wars has beneath it this flawed thing: a revolutionary organization.

The last several decades have produced a deluge of ideas about the ongoing nature of Western imperialism. It is perhaps the unique necessity of narrative to force ideas into a particular world and context—for ideas to exist as living things, between characters, evolving through plot—reminding us that ideas do not simply remain static or exist on their own. Because of the cross-temporal nature of mass media franchise, this historicizing of ideas is unavoidable. The “presentness” of Andor is a byproduct of its existence in a franchise that has evolved alongside the same cultural, historical, political, and economic forces to which the original Star Wars was responding to. We are simultaneously thrust back into the historical moment from which the original Star Wars emerged and the acute crises of our present—not as analogy, but an actual conversation between historical and present contradictions, and the role of media, culture, and narrative in mediating between the two. What might considering the conditions from which the original 1977 film emerged illuminate about the emergence of Andor as an explicitly anti-imperialist and anti-fascist text in a moment of crisis?

In 1977, when the original Star Wars released in theaters and quickly became the highest grossing film of all time, outer space and technologically-driven empire were the subjects of headlines, not plastic toys and kids costumes. The United States had only left Vietnam two years prior, after nearly two decades of war against anti-colonial revolutionaries. In the very same year, NASA launched the Voyager 1 and 2 probes, two of the only objects to have left the solar system, with an interplanetary archive of humanity and greetings to any extraterrestrials who might one day find them. The Walt Disney Corporation also celebrated the launch of their new ride, Space Mountain, as the crowning attraction of Tomorrowland—the futuristic foil to the park’s western-themed Frontierland. Tomorrowland’s aesthetics were shaped in collaboration with Wernher von Braun, the Nazi-turned-NASA-engineer who designed the Saturn V rocket that sent the Apollo astronauts to the Moon.3Catherine L Newell, “The Strange Case of Dr. von Braun and Mr. Disney: Frontierland, Tomorrowland, and America’s Final Frontier,” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 25, no. 3 (2013): 416-429. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/533726. (Notably, after Disney bought Star Wars, Tomorrowland has been re-fitted with franchise-themed rides—with Stormtroopers patrolling this strange mix of retro-futurism and recreations of iconic Star Wars sets.) In the two decades after the end of World War II, the world had witnessed the defeat of Nazi Germany, the rise and expansion of the military-industrial-complex (more comprehensively, the military-industrial-academic-entertainment-complex), and the horrors of Vietnam—considered both the first “technowar” and the first televised war.

Exponential changes in the mechanisms of war and modes of communication that provided access to it were central parts of the milieu from which George Lucas wrote and directed his children’s fable about a group of guerilla fighters that defeat a Galactic Empire. The importance of the original film focusing both on the Death Star as a superweapon, and the communication of its technical schematics as the key to the Rebellion’s victory, provides an opening between the shifts in technological warfare and communication in 1977 and in 2025, where the world has been witness to the first genocide broadcast on social media and implemented with a vast apparatus of surveillance technologies utilizing artificial intelligence. The historical processes to which 1977’s Star Wars was responding to have continued to evolve. Because Andor takes the premise of the original film seriously, namely, that it is fundamentally a revolutionary and anti-imperialist text, it necessarily must respond to the contemporary crises of late-stage capitalism and US-led neoliberal hegemony and the suggestion that it is on its deathbed. In the process, it (re)produces the inescapable contradiction at the heart of contemporary American culture: that the most technologically powerful empire the world has ever known contains within it the mythos of revolution.

While the Empire certainly channels fascist aesthetics that evoke Nazi Germany, Lucas has been clear that American imperialism was at the core of his thinking when making the film, and that the rebels are analogous to the Vietcong rather than the Allies. It is, after all, a Senate that is dissolved in the film’s opening act, not a Parliament akin to Weimar German’s Reichstag. But far more significant to 1977’s Star Wars than the political mechanisms of democracy’s death (a focus of Lucas’ prequel trilogy from the early 2000’s) is the source of the raw power that enables the pretense of democracy to drop: the Death Star.

The introduction of the Death Star is positioned within the original film as an escalation of imperial authority that produces an existential threat. Off-screen, the planet-killer can be seen as an escalation of the scale of imaginative destruction, putting the dreams of a nuclear-weapons-station in orbit from earlier science fiction to shame. The destruction of Alderaan halfway through the original film—what to the contemporary viewer seems mild in comparison to the galactic-genocide-by-snap stakes of blockbusters today—was one of the first visualizations of the instant death of an entire planet to be put on film. Before the construction of the Death Star II off-screen between The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, before the comically derivative “Starkiller” of Disney’s Star Wars debut in The Force Awakens (now five planets can be destroyed at once!), there was the original Death Star—a not unimaginable creation in the newly-ushered-in atomic age around which the plot of the first film revolves. Luke Skywalker’s collision with destiny emerges narratively, more than anything else, through his coming into contact with technical schematics. In the aftermath of the scramble for members of Nazi Germany’s technical and intellectual labor force by both the US and USSR, and the ongoing race to develop rockets capable of delivering larger and more destructive nuclear weapons, and the televised assault on any anti-colonial revolutionaries that dared to defy the interests of the United States, Star Wars presented the superweapon-to-end-all superweapons as fallible, containing a flaw so small as to be overlooked by imperial bureaucracy: the vulnerable exhaust port that ultimately allows the rebellion to claim victory by the two-hour epic’s end.

This opening—of the Death Star’s fatal flaw—has not only served the Rebellion, but provided a key opening for the future of the Star Wars franchise after its 2012 acquisition by Disney. While the trilogy of movies intended to follow the establishment of a New Republic following the Empire’s defeat has floundered (in an almost comical move, J.J. Abrams’ The Rise of Skywalker resurrects Emperor Palpatine between movies to serve as an antagonist), the most critically successful projects have specifically sought to re-contextualize the Death Star’s fallibility. Rogue One, set the week before the events of the original film, re-stages the Death Star’s flaw not as a technical error, but an intentionally placed vulnerability by the station’s lead engineer, Galen Erso, whose family was destroyed by the empire. Cassian is first introduced in this film as a rebel spy sent to assassinate Erso, whose daughter Jyn is the film’s protagonist. The film’s plot takes place over the week before the original Star Wars, and sees the entirety of the ensemble cast die in the effort to steal the Death Star plans that detail the station’s vulnerability from a data vault, with Jyn and Cassian the last to perish in a blast from the Death Star’s beam.

The finality of Rogue One’s ending stands in stark contrast to the cheapness of death in many of Disney’s other entries into the franchise, with the above-mentioned Rise of Skywalker not only resurrecting the emperor, but consistently “killing” fan favorite characters only for them to be revealed alive and well moments later. The defeat of “The Final Order” that the cloned-Emperor developed in secret comes about because Lando Calrissian zips around the galaxy off-screen to call in several thousand favors to amass a volunteer fleet. While ostensibly this could be generously read as some notion of “people power,” in practice it is entirely vapid—the closest theory of change being one akin to an influencer turning out their fanbase for a symbolic protest. Of course, we should not be asking for revolutionary praxis from Star Wars—which is precisely why the existence of Andor at all is so puzzling, especially when the broader franchise within which it exists is often so politically tone-deaf.

Despite Rogue One’s success, no fans were clamoring for a spin-off focused on Cassian Andor. Disney’s original concept was an ill-advised “buddy cop”-style show with Cassian and his robot companion K-2SO, a reprogrammed imperial droid, as part of their slate of Star Wars TV shows to populate Disney+ as it entered the increasingly-crowded streaming market in 2019. It was, apparently, because Tony Gilroy—who was brought in to guide re-writes and re-shoots of Rogue One’s troubled production—insisted to producer Kathleen Kennedy that a more grounded, historically-informed prequel meditating on the nature of revolutions would be the way to approach the show that Gilroy was eventually brought on4Adam B Vary, “How ‘Andor’ Became the First ‘Star Wars’ TV Series for Grown-Ups: ‘I Wanted to Do It About Real People’,” Variety, August 24, 2022. https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/star-wars-andor-tony-gilroy-diego-luna-1235348148/.. Gilroy, it is worth noting, had a close working relationship with Kennedy, who he claims allowed him complete creative control over the project.5Anthony Breznican, “Andor Finale: Creator Tony Gilroy Breaks Down the Star Wars Spy Saga’s Gut-Wrenching Ending,” Vanity Fair, May 13, 2025, https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/story/andor-finale-tony-gilroy-interview. In other words, Andor exists in part because of Hollywood nepotism.

The particular form the first season ended up taking was also profoundly shaped by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused production to completely shut down and, after almost killing the show, allowed a “re-boot” of sorts. Scripts were revisited, and shoots were required to be planned meticulously to cohere with COVID-19 protocols. The result of these conditions was a much more intentionally written and produced show6Tony Gilroy, “PaleyLive: An Evening With Andor,” moderated by Patton Oswalt, panel discussion, May 30, 2025, posted June 3, 2025, by The Paley Center for Media, YouTube, 41:30 to 44:20, https://youtu.be/b_M9VSSRBMQ?si=G0ElxSMt_mWOYZQF.. These were the conditions produced by the event of the COVID-19 pandemic—those with access to financial stability, support, and time were placed in conditions conditioned, to some extent, from the normal pressures and operations of capital as it struggled to adapt to a truly global crisis. The result was a first season crafted through a meticulous (and expensive) production that took two years to be completed.

While the original plan for the show was to cover the five years before Rogue One across five seasons, Gilroy and Luna realized this would lead to the project taking a decade—maintaining the quality and scope of the first season across a five-season arc would simply take too long (and likely become an increasingly difficult sell to Disney, at a cost of about $27 million per episode).7Scott Feinberg, “Tony Gilroy Says He Can’t See Himself Doing Anything Like ‘Andor’ Ever Again,” The Hollywood Reporter, August 19, 2025. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-features/tony-gilroy-interview-andor-1236342635/. The current TV and streaming landscape has few shows that last more than two or three seasons, much less shows with the production value of Andor. Thus, the grounded, meticulous, and detailed nature of the show’s first season that emerged in part from the conditions of the pandemic became unsustainable in the “post-COVID” era, with its return to accelerated capital.

The solution was a second season with an accelerated structure: each set of three-episode arcs took place one year apart, allowing the season to cover the four-year gap between the first season’s end and the beginning of Rogue One. The result is what Gilroy has described as a kind of “needle drop” structure, where the show dips into particularly heightened and intense inflection points that trace the increasing fractured nature of the Empire’s bureaucracy and the emergence of the Rebellion as an organized institution.8 9Brian Hiatt, “Andor’s Showrunner Reveals Season 2 Secrets And Why Writing Darth Vader Is ‘Limiting’,” Rolling Stone, April 25, 2025, https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-features/andor-tony-gilroy-season-2-interview-darth-vader-1235324435/.The show, then, is able to maintain the meticulously crafted storytelling of the first season across a much wider temporal and historical scope, thereby producing an almost accelerationist structure in which the viewer has these limited windows into sweeping historical forces, and we are encouraged to imagine the events taking place in-between the gaps. That this structure is an artistic response to the conditions of capital shaped in reaction to the mass death event of the pandemic should also position us to consider Andor’s second season as both engaging with and shaped by the historical conditions that have allowed it to come into being. That the independence of its creative construction was made possible, in part, through its creator’s longstanding relationship with a Hollywood executive might actually deepen our understanding of the contradictions the show is grappling with rather than inviting the show’s dismissal as a text for politically-oriented analysis.

Within the world of the show, the character of Luthen is most in tune with the scope of the historical changes that become increasingly visible through the series’ second season. Luthen is also a chameleon: his public persona as the owner of an antique shop in the Galactic Capital, Coruscant, is cover for his role in shaping the conditions that allow revolutionary potential to ferment. Explicitly an accelerationist, Luthen hires Cassian for the heist that funds the rebellion’s beginnings, and produces the connective tissue between parallel narrative threads and sites of struggle across different scales. What comes into view is a network of seemingly contradictory tactics that are all staged as necessary to allow the Rebellion to come into being. The show moves from arranged marriages to dinner parties with Imperials to prison breaks and attempted assassinations of Imperial officers. What is necessary, the show insists, is not always what is moral. Complicity with the collapsing institutions of liberalism, the murder of allies that may prove to be liabilities, the instigation of Imperial repression that will almost assuredly harm innocents—these are all tactics that Luthen implements and instigates without any claim to justify his actions on anything but pragmatic terms. And yet at the same time, the show continuously resists the impulse to render final, negative judgement against the revolutionaries.

Saw Gerrea, originally introduced in the animated Cartoon Network series The Clone Wars and later played by Forrest Whittaker in Rogue One, becomes a fascinating litmus test for this dynamic. He is the leader of one of the more revolutionary organizations that emerge before the institutionalization of the Rebellion. Deeply skeptical of Luthen, he refuses to ally with any one group. Often, Gerrera appears in the broader Star Wars universe as a foil to more tempered, morally clean heroes and an example of the dangers of committing oneself completely to the cause. Andor shies away neither from his militancy nor his strangeness as a character, but fundamentally grounds him as a human and necessary participant in the wider network of revolutionaries—and capable of tapping into and sharing the beauty of revolutionary fervor, the fuel necessary to commit oneself completely to a project from which one is unlikely to ever reap personal benefits. The most intimate view of Gerrera comes through the eyes of Wilmon Paak, Cassian’s childhood friend, who is essentially manipulated into assisting Gerrera in preparing to blow up a pipeline of Rydonium—a volatile starship fuel whose fumes produce an addictive high. One cannot help but be convinced by the scene’s momentum as Saw convinces Wilmon to take part in the fumes, producing a clear thesis: “We’re the rhydo, kid. We’re the fuel. We’re the thing that explodes when there is too much friction in the air. Let it in, boy! That’s freedom calling! Let it in. Let it run! Let it run wild!” There is a build and release as the viewer becomes enveloped into the process of radicalization Wilmon is undergoing, the soundtrack pushing us to elation alongside the peak of Wilmon’s high. Saw is no longer the half-crazed revolutionary whose presence allows the Rebellion to be situated as distinct from the “real terrorists” of the Star Wars universe: he teaches the audience, through Wilmon, something essential about the nature of rebellion. We never see the pipeline blown up, we don’t need to. The scene’s true climax is the emergence of political and historical consciousness in Wilmon, an invitation for the viewer to safely approach the question of political violence through a speculative frame.

At the other end of the spectrum of political action is Mon Mothma, who has become a figurehead for the Rebellion in the original trilogy but for much of Andor remains within the realm of Coruscant’s upper political class. As a Senator, Mon Mothma’s liberal façade creates cover for Luthen to distribute capital to his network. Like most of the show’s ensemble, Mon Mothma spends the majority of the show isolated from the other terrains of struggle. Her actions, however, are consistently illustrated to be just as essential to the broader movement as those of Gerrera or Cassian.

The second season’s accelerated pace allows the audience a unique vantage point from which to witness the collapse of many of these scales as they begin to collide with one another, producing moments of surprise as we realize how much less each of these characters knows about each other than we know of all of them. Cassian never meets Guerrera on screen, though he is connected to him through his Wilmon’s continued importance in the narrative. Both advocate taking seriously Luthen’s intel that leads to the Death Star plans after his death. Syril Karn—the overzealous “good cop” whose pursuit of Andor at the show’s start sets off his path towards becoming a revolutionary—only meets Cassian moments before his death. Their paths collide in the midst of the chaos on the Ghorman square, during the Empire’s assault to pave way for strip-mining the planet for the minerals that will power the Death Star. In a sense, Syril is one of the characters most responsible for Cassian’s radicalization, and Syril’s pursuit and hatred of Andor is central to his belief in justice. As Syril realizes his commitment to the rule of law has allowed him to be manipulated into facilitating a genocide, he simultaneously realizes that Cassian—who simply asks, “Who are you?” after Syril attacks him—has no idea who he is. The drama here is historical, not interpersonal, as the processes of alienation and mediation between these different spheres of social life becomes precisely the dance through which the plot of the show primarily operates.

Similarly, Mon Mothma only meets Cassian in the following episode, after exiting the stage of the Senate and abdicating her role among the political elite. Her final speech—in which she names the Empire’s actions on Ghorman as a genocide—requires her immediate evacuation to the rebel base on Yavin, facilitated by Cassian. There is an almost comic element to the collision of these two protagonists for the first time, perhaps best highlighted from the now memeified moment when Mon Mothma is shocked at Cassian’s casual murder of her driver, an Imperial spy, during their escape. The methods of resistance each has practiced within their theater of struggle, violent and non-violent, are smashed violently together. And yet the show positions both as necessary—indeed, it is Mon Mothma’s placement at the Galactic Senate long past its fascist turn that allows her to introduce the resistance on the cosmo-political stage as her public persona transitions from liberal senator to figurehead of the now-institutionalized Rebellion.

The instigating action for the show’s final arc also is triggered by a first meeting of two core characters: Luthen and Dedra Meero, the imperial spy who has been dedicated to tracking down him down (known to her as “Axis”) throughout the show. Staging the point made by the return of Nemik’s manifesto, Luthen tells Dedra: “You’re too late. The rebellion isn’t here anymore. It’s flown away. It’s everywhere now.” Once under the boot of oppression, the galaxy is now in open rebellion. This transformation is presented as something beyond the scope of what can be put on screen. Rather, these collisions of scale and collapsing of worlds are gestured to in small moments such as these and grounded by a series of personal transformations throughout the show. But rather than such interactions involving the Empire’s enactment of its worlding on all those other forms of community and living, the characters whom we have followed—most of whom will never see the version of the Rebellion first put on screen in the 1970’s and 80’s—have set the conditions for the Empire’s failure. Dedra believes she has achieved the task set out before her since the show’s start, and yet her very pursuit of that goal is what sets about her undoing.

It is this intricate layering of conditions at different social strata and institutional positions, within and outside of the imperial bureaucracy—both shaped by Luthen within the show, but also by the steady hand through which Gilroy has traced these enmeshments for the audience—that sets the stage for the lead-in to 2016’s Rogue One and, by extension, 1977’s Star Wars. When Lonni Jung, the rebel spy placed by Luthen in the ISB, discovers that Dedra has inadvertently amassed classified information on the Death Star project in her attempt to locate Axis, this data—for much of the series’ final arc, simply a memorized string of keywords passed from one person to another—ricochets through the communications structures established over the last two seasons. Because the audience has been given a broad and long view of the construction of these conditions, the individual actions of particular characters are understood as only meaningful because of the broader movement of which the potential for such actions has emerged. It is worth admiring the intricate design of Andor’s narrative. It is more important, however, to see that this focus on disparate sites of struggle that, over the course of several years, converge and cascade in the movement towards the franchise’s source text produces a valuable and unusual kind of historical consciousness.

The ability for revolutionary struggle to occur at different scales simultaneously, and for modes of communication to remain open between them, becomes essential to the ultimate defeat of the Death Star. Technology—in particular, technologies of communication and the data and information they are capable of transferring—comes into view as an essential category not only for Andor, but the broader staging it creates around the original Star Wars film. If we understand the 1977 film to be specifically about the emergence of a technological Empire, the production of a complex superweapon, then Andor’s particular focus on technologies of mediation encourages a dialectical perspective that is all too rare.

A strange aesthetic consequence of franchise-storytelling is that some of the most expensive and spectacle-oriented cinematic productions must conform to the basic designs of what the future was imagined to be in the 1960’s, 70’s, and 80’s. By having to craft a narrative within the particular possibilities and constraints of the logics of a world constructed in the 1970’s, technology as much as the underlying thematic elements of the narrative is placed within a kind of cross-temporal bind as well. This produces a situation like that of Star Wars where storytelling takes place in a universe where faster-than-light travel exists, but the internet does not. Andor’s sets are filled with expansive panels with physical buttons reminiscent of telephone switchboards, telegraph-like devices used to send messages in morse-code, clunky earpieces and headsets. There is a tactile nature to how the passage of information is traced—one manipulated by the empire’s use of propaganda, while simultaneously essential to the establishment of Luthen’s network. Considering the role Disney has played historically in constructing the aesthetics and imaginaries of American space-travel, and the direct links of that project both to Nazi Germany and Western expansionism in the U.S., the question of how one engages with communications networks and media technologies to resist an empire while also being inevitably embedded within them becomes far less abstract.

One of the other consequences of Star Wars as a cultural phenomenon is its role in inspiring generations of children and students to grow up and pursue careers as aerospace engineers—the primary intellectual labor base for the U.S. defense industry. Signs of Star Wars’ influence, and that of other science fiction franchises, can be seen across space technology projects at NASA, SpaceX, and others. The connections between science fiction and defense predate Star Wars and its current expansion as a franchise, with the nicknaming of Ronald Regan’s Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) as the “Star Wars” program being perhaps the most obvious example. But the second generation of workers who supplied the labor force for the intellectual work of the military-industrial-complex largely came of age within the aesthetic milieu of many of the original stories that have now become franchised. The expansion of a self-cannibalizing mass media culture premised around nostalgia exists alongside an interplay between entertainment focused on technological spectacle and the inspiration to work to produce aerospace technologies that lodge some of these aesthetics and imagined technologies into reality. But what happens when the act of revolution becomes the focal point of how one approaches Star Wars, to such an extent the spaceships become almost negligible?

The argument I am making is not simply to have faith in art’s power to inspire political change—even art with a rare combination of commercial reach and political messaging. Rather, it is to say that a confluence of historical, economic, and aesthetic conditions produced the text of Andor within the narrative world-system of Star Wars. There is some movement of forces through time that have led to that possibility, and within those forces contains the desire to rebel against forces not unlike those we currently face. Grappling with the movement of stories and ideas through time—how they shape both culture and each of our lives within it—primes us to re-situate what might be asked of us in our present moment. A Star Wars show is a strange place to address possibilities for deepening political consciousness, but considering the overlaps between the aesthetics, imaginaries, and fruits of the inspiration produced by the franchise with the military-industrial-complex, and the seriousness with which Andor asks its audience to take the anti-imperialist thrust of the franchise’s source text, that contradiction produces generative possibilities.

One kind of Star Wars story has defined American culture, despite the best efforts of the more interesting entries into the franchise: that of good against evil, blue lightsabers against red, clear heroes and villains. Andor asks us to consider another—one concerned with the project rather than simply the aesthetics of rebellion, easily decontextualized and depoliticized. What kinds of defection from the ongoing forces of imperialist violence that may ask of us, where we might locate ourselves within one terrain of struggle among many, has no pre-determined answer. Star Wars has undeniably played a part in inspiring generations of aerospace workers to help build weapons of war—weapons developed with the tax dollars of every U.S. citizen and resources amassed by neocolonial and neoimperial plunder. What might dislodging the stable basis of those dreams produce instead? Meeting the gap between the recycled dreams of the past and the present they have wrought is precisely the question of what it means to develop some form of historical—and potentially political—consciousness. What is done with the opening that produces, even if it is no larger than the exhaust port of a moon-sized space station, is the question in play at this current juncture of imperial decline.

Works Cited

Breznican, Anthony. “Andor Finale: Creator Tony Gilroy Breaks Down the Star Wars Spy Saga’s Gut-Wrenching Ending.” Vanity Fair, May 13, 2025. https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/story/andor-finale-tony-gilroy-interview.

Césaire, Aimé. Discourse on Colonialism. Translated by Joan Pinkham. Monthly Review Press, 2000.

Feinberg, Scott. “Tony Gilroy Says He Can’t See Himself Doing Anything Like ‘Andor’ Ever Again.” The Hollywood Reporter, August 19, 2025. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/tv/tv-features/tony-gilroy-interview-andor-1236342635/.

Gilroy, Tony, Diego Luna, Sanne Wohlenberg, Genevieve O’Reilly, Adria Arjona, and Ben Mendelsohn. “PaleyLive: An Evening With Andor.” Moderated by Patton Oswalt. Panel discussion on May 30, 2025. Posted June 3, 2025, by The Paley Center for Media. YouTube. https://youtu.be/b_M9VSSRBMQ?si=G0ElxSMt_mWOYZQF.

Hiatt, Brian. “Andor’s Showrunner Reveals Season 2 Secrets And Why Writing Darth Vader Is ‘Limiting’.” Rolling Stone, April 25, 2025. https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-features/andor-tony-gilroy-season-2-interview-darth-vader-1235324435/.

Newell, Catherine L. “The Strange Case of Dr. von Braun and Mr. Disney: Frontierland, Tomorrowland, and America’s Final Frontier.” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 25, no. 3 (2013): 416-429. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/533726.

Reid, Caroline. “Disney Reveals $645 Million Spending On Star Wars Show ‘Andor’.” Forbes, Dec 22, 2024. https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolinereid/2024/12/22/disney-reveals-645-million-spending-on-star-wars-show-andor/.

Vary, Adam B. “How ‘Andor’ Became the First ‘Star Wars’ TV Series for Grown-Ups: ‘I Wanted to Do It About Real People’.” Variety, August 24, 2022. https://variety.com/2022/tv/news/star-wars-andor-tony-gilroy-diego-luna-1235348148/