This is probably too surface-level a claim with which to begin a review, but, anyway: despite its giggily title, the gold-rush-era Western The Sisters Brothers, which is based on the novel by Patrick deWitt, is not a comedy. It’s definitely not. It’s helpful to know this before seeing it, lest you become distractedly shocked by the film’s myriad representations of such viscerally unpleasant elements as: severe maiming of the skin, gruesome animal deaths, expulsions of bodily fluids, and nineteenth-century medical practices. The constant prompts for shock and repulsion are superbly engineered, emblematic of the film’s technical prowess, and all have important metaphorical meanings. But for those of you who would have wandered to a screening specifically because of the clever title or the presence of several enjoyable actors or maybe because you read deWitt’s most recent novel French Exit (which is about bankrupted Manhattan socialites absconding from the continent and will doubtlessly be adapted to film by Whit Stillman someday), here’s your warning. The body count is large (accounting for its being the “shootout” kind of Western). There’s lots of pooling blood. And something happens with a spider that I don’t want to get into for fear of spoiling a truly creative bit of symbolism, but which I want to mention at all because it does have the power to mess you up, if you’re that sort of person.

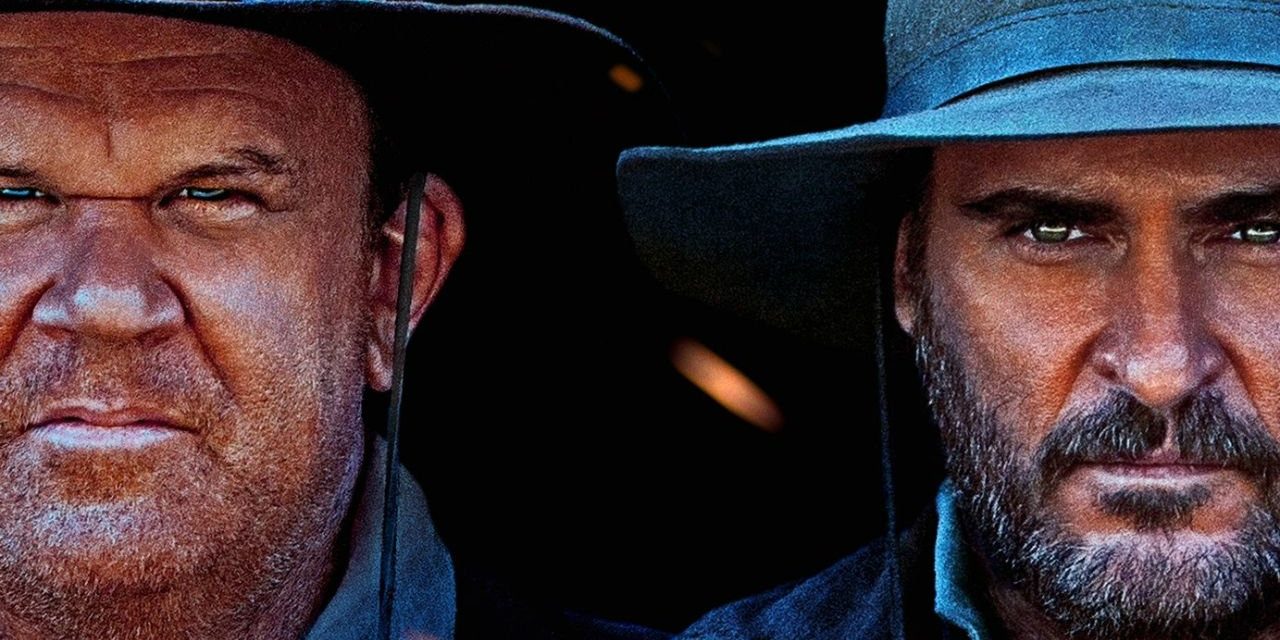

The Sisters Brothers follows Eli and Charlie Sisters (John C. Reilly and Joaquin Phoenix)—quarreling hitmen-on-horseback who work for a sinister tycoon called the Commodore (Rutger Hauer, but barely—he’s only onscreen for a minute). After a botched job, they are forced to collaborate with a detective, John Morris (Jake Gyllenhaal), to capture a young chemist named Hermann Kermit Warm (Riz Ahmed). Warm is headed via covered wagon west to California to try to strike it rich as a prospector. Though no one knows it yet, Warm (a super nice guy, for the record) has developed a chemical formula for a substance that can reveal the locations of gold in riverbeds—gold he plans to mine so he can go build a city-on-a-hill, an ideal society of his own creation based on respect. (It’s in Texas.)

The first English-language film by Jacques Audiard—who made the whiplashy crime film A Prophet in 2009, the bleak romance Rust and Bone in 2012, and the gut-wrenching drama Dheepan in 2015—The Sisters Brothers sizzles in all compositional respects, particularly when it shuffles visual conventions of the genre with some exciting new ideas (a scene in which the brothers, on horseback, ride right up to the Pacific Ocean immediately comes to mind). Audiard is a master commander of space, darkness, and dirt, and the film’s many free and limitless landscapes are punctuated with lonely, desolate, campfire-lit nights—days of sweat turn into bedtimes of grime. Eli, in particular, becomes preoccupied with staying clean.

With these moments, the film begins building a chafing relationship between the brothers and nature. For a while, this is pretty anthrocentric; the brothers’ gradual sousing with filth, soil, and other base organic elements directly correlates with the endless violence that is escalating in their lives and reveals the depths to which they have sunk away from the social contract and basic morality. Writing from Audiard and Thomas Bidegain provide the film’s few, truly funny moments, mostly in the form of witty, rather Odd-Couple-esque banter between the sensitive, know-it-all Eli and his careless, teasing, and frequently-drunk younger brother Charlie. Eli is growing weary of the never-ending cycle of violence in his life, while Charlie is just getting started.

The film does its most interesting work halfway through when it abandons virtually all expectations of the chase narrative (the particular brand of Western that it has been thus far) in favor of a new governing emphasis: manifest destiny. But unlike the genre’s many explicit takes on this topic, The Sisters Brothers is not concerned with geographical or colonial varieties as much as the environmental. Developing the brothers’ tense relationship to nature that begins in the film’s wrecking ball of an opening scene, when their carelessness causes a barn full of horses to be set on fire, there arises a new plot of scientific advancement in the face of natural destruction.

Warm does not know the extent of this, but his divining chemical is highly toxic, and, when unleashed on California’s fresh water supply, will have massive ecological ramifications. Wonderment at the natural world has always been a component of the Western genre, and with each featured barn-raising and frontier outpost, such films do hint that this majestic land will be threatened by human expansion. But rarely in this genre (and this is thanks to deWitt’s novel, too) is the ongoing environmental precariousness of the American wilderness framed so explicitly as in The Sisters Brothers, whose ecosystems are severely mutilated by mankind. Unlike many in its genre, the film does not agonize over industrialization so much as the responsibilities necessarily attached to invention—of the dangers of scientific progress made even by a single brilliant man with good intentions.

The film insists that its audience be just as hypnotized by the side-effects of their (unnecessary) human work. As it is ruined, nature is depicted as beautiful—or at least, captivating. As the doomed horses in the first scene catch fire, one breaks free and charges away with its mane, back, and tail blazing brightly as it runs, streaking like a comet through the woods. The camera lingers on this burning animal too long as it runs in pain. When Warm finally spills his chemical into the freshwater river where he will find gold, it lights up bright green—ectoplasmic and bewitching in the moonlight. These horrifying, engrossing images unite the blundering hitmen and the brilliant scientist. It’s possible that this sudden pairing might aim to illuminate how the Sisters brothers, with their trail of bodies and scarred earth behind them, might be festering and infecting Warm’s well-meant endeavor. Violence and destruction, the film reminds its viewers, cause more of the same. But it’s also likely that the film has a double-pronged understanding of evil. Murder is bad, sure. But it’s worse, maybe, to poison a water supply and ruin a habitat.

Eli Sisters may be the only character in the film who picks up on even a glimmer of all this, and his perceptiveness is impressive, since he has to spend a lot of time babysitting Charlie. At its barest minimum, The Sisters Brothers does a really good job ignoring that its main propelling motif is that a hitman has a heart. But the film itself is a sad, sagacious yarn about sacrifice, of many kinds, the most important being the kind we don’t know we’re submitting to: living with the hell we’ve raised and the monsters we’ve encouraged, simply because we’ve become so determined to move forward. Not a single one of the atrocities onscreen is more stomach-churning than the combo of others’ willful ignorance and your own regular guilt.