Kevin McAuliffe wrote a book subtitled The Rise and Fall of the Village Voice in 1978, six years before I arrived there and 23 years after the Voice’s founding. Ed Fancher, who started the paper along with Dan Wolf and Norman Mailer, has noted that the three of them fought in World War II and began the Voice in part as a response to the closed and defensive mood that took hold after 1945: there was “a feeling that there should be an open society, and that would require an open sort of newspaper, which The Village Voice was.” The Voice rode every subsequent counter-cultural storm, and since such storms end with a measure of disappointment and recrimination, each Voice generation suspected the one before it had been better.

I’d come out from UC Berkeley, where I had paid my way through school by working for The Daily Californian, which at that time was itself an off-campus, counter-cultural daily (except weekends) newspaper run by students. I was serenely confident in the bright future of alternative media, which at that time meant left-leaning media. The mainstream media (not that we called it that) was liberal to conservative, in either case a guardian of the status quo. It had had very mixed feelings about jazz, beatniks, abstract art, the anti-Vietnam War movement, recreational drugs, hippies, environmentalism, French movies, civil rights, feminism, gay rights, and a great deal else, such that the field of opportunity for the left-leaning counter-cultural media was immense. There was no radical-right equivalent; the cultural contest was between the left and the status quo.

The term “culture” itself, for the Voice’s first few decades, was something of a counter-cultural property in the revolt against the middlebrow and the square. In many ways, the counterculture was elitist. Alex Cockburn, who had an incandescent Voice run in the 1970s, liked his Latin tags. The Voice’s film critics of that period (Jim Hoberman, Andy Sarris, Carrie Rickey) were well schooled in the nouvelle vague, the Dziga Vertov Group and the experiments of Chris Marker. But of course it was a demotic epicureanism, especially among the music writers, who week after week combined words like “stank”, “arpeggio” and “autochthonous” in sentences of onrushing slangy erudition. The Voice was a place where people regularly cooked up phrases like “demotic epicureanism”. It was a highly competitive, unaccredited, endless graduate school for people who, like me, could not afford real graduate school and in many cases had little benefit of formal education. It really was bohemian, in that and every other sense I can think of. Underneath was a profound seriousness of purpose. Our claim was that sophistication was itself popular: the Duke Ellington claim.

This made conventional politics tricky. For many Voicers, electoral politics was inherently compromised, something to be critiqued but not invested in as it could never deliver the systemic change we tended to long for. This was a snobbish position but it was also not at all far from the enduring lower-class view that party politics is a stitch-up. The Voice’s work-around was in fighting corruption. The Voice had a ferocious investigative side. I had the fraught honor for a while of editing Wayne Barrett, who set the paper’s standard for afflicting the powerful. It was he who said in a heated moment, “I don’t write for readers, I write for prosecutors,” or words to that effect. That was the truth.

My acceptance at the Voice came as the result of several manuscripts I sent through the mail, particularly some thousands of words of reporting on the British coal-miners’ strike of 1984. I was completely unknown and penniless – my savings had gone into visits to coal mines and a fever-ridden wander across North Africa — and had just turned 23. In the past few years there has been a lot of Facebook reminiscing among surviving generations of Voice hands and it’s striking how many came to the paper in about the same way. Driven people, at least as insecure as most, but with a sense of their potential greatness and a determination to overcome any obstacles to achieving it. These were, on the whole, not privileged people; many came from groups that were marginal to the mainstream of the time; and most arrived with a conviction that they already knew how to tell the stories, in words, pictures, and graphic design, that they wanted to tell, and the Voice was the place, perhaps the only place, where they would be able to tell them.

Precisely why the Voice was the destination of choice is hard to pin down. In part it was the coherence of the American counter-culture – which is related to the coherence of the status-quo culture – from the 1950s through the end of the Cold War. Success in such a coherent counter-culture was success in itself, not an early success on the way to something else, which is why the Voice’s achievement cannot be measured by totting up the names of people who went on to careers in publications that are not now being wound up with a sigh by their owner. It is a category mistake to talk about the Voice’s “influence”. Whenever I look back on the Village Voice, where I wrote and edited from 1984 to 1997, it just gets better. Much of its best work was by people whose professional achievements – if “professional” is the right word – were mainly limited to the Voice itself. The current owner, Peter Barbey, has said that while the Voice will no longer be producing original content he wants to continue to work on digitizing its archive. I hope he sticks to that. The Voice has failed to survive, but in every other way it won.

***

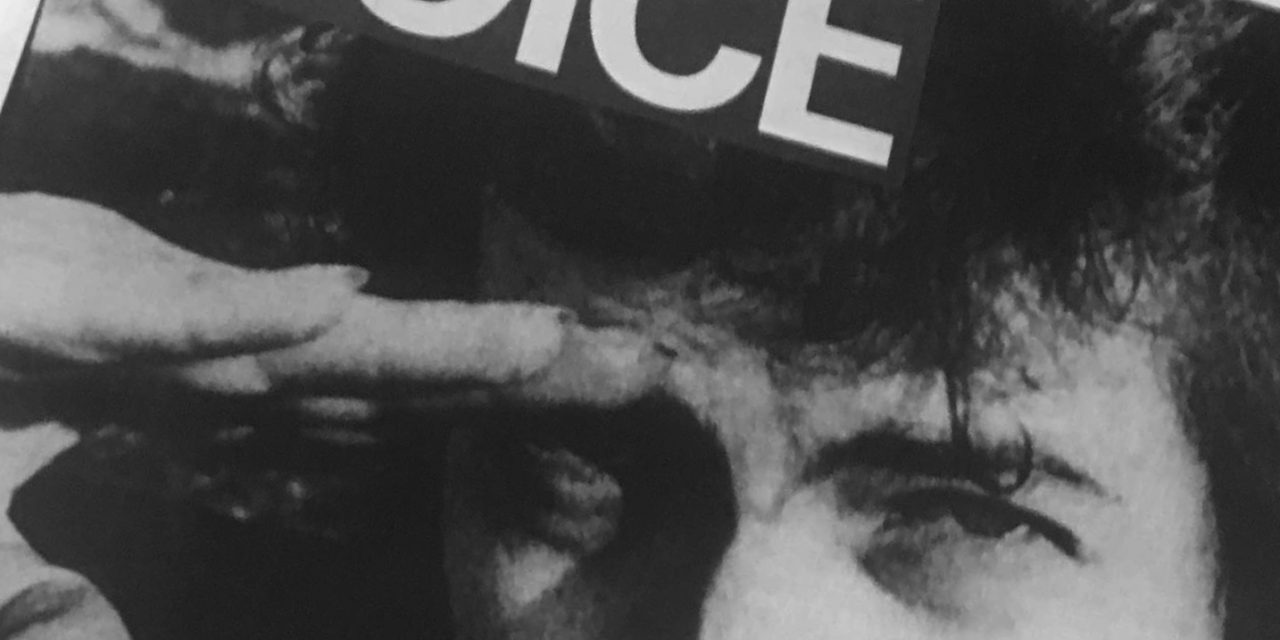

Photo of Bob Dylan used on the cover of the final print edition of the The Village Voice by Fred W. McDarrah.