Drawing, according to John Berger, is an act of discovery. “It is the actual act of drawing,” he wrote in 1953, “that forces the artist to look at the object in front of him, to dissect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again; or if he is drawing from memory, that forces him to dredge his own mind, to discover the content of his own store of past observations.” I would add that it is also a means of knowing, of analyzing critically the world around you. And it is this understanding of drawing that has spurred me to keep sketchbook/journals for the past five years. As receptacle of unfiltered observations, both visual and literary, these sketchbook/journals have helped me process and make sense of my surroundings, and in doing so, make sense of my own thoughts and attitudes.

The contents of my sketchbook/journals range from random musings on topics like love and sexuality, and sketches of everyday life on the New York City subway, to critical observations of American political economy. I draw and write often at bar, where I might start with a sketch of a pint. I might then move on to sketching, both visual and textually, my surroundings—the attitude of the bartender, for example, snippets of unusual conversations, or profiles of strange characters that I inevitably attract. Throughout, I challenge my assumptions, and attempt to historicize my experiences. If nothing else (aside from a chronicle of my drinking habits) these sketchbook/journals represent an honest, idiosyncratic perspective of American life, however narrow. Similar to how Berger understands drawing, my sketchbook/journals are a means of self-inquiry and reflection through which I generalize about my experiences as I travel.

This group of pages is from a recent trip to the West Coast. I’m a graduate student, and work on 1970s American popular culture. I received a grant to visit the Richard Nixon Presidential Library and in Yorba Linda, CA, which is what brought me out west. Most of my trip, however, was spent dancing, and partying. I was based in Westwood, Los Angeles for the first leg of my adventure, and then moved on to San Francisco before returning east. My experience in LA was unique in that I was visiting a grad school friend. Her family lives in Malibu, among movie stars. She likes to boast that a Cornell flag flies in Michael Keaton’s window in her honor; She’s a family friend with Tom Hanks who attends her Greek Orthodox Church. In many senses, this was a surreal situation.

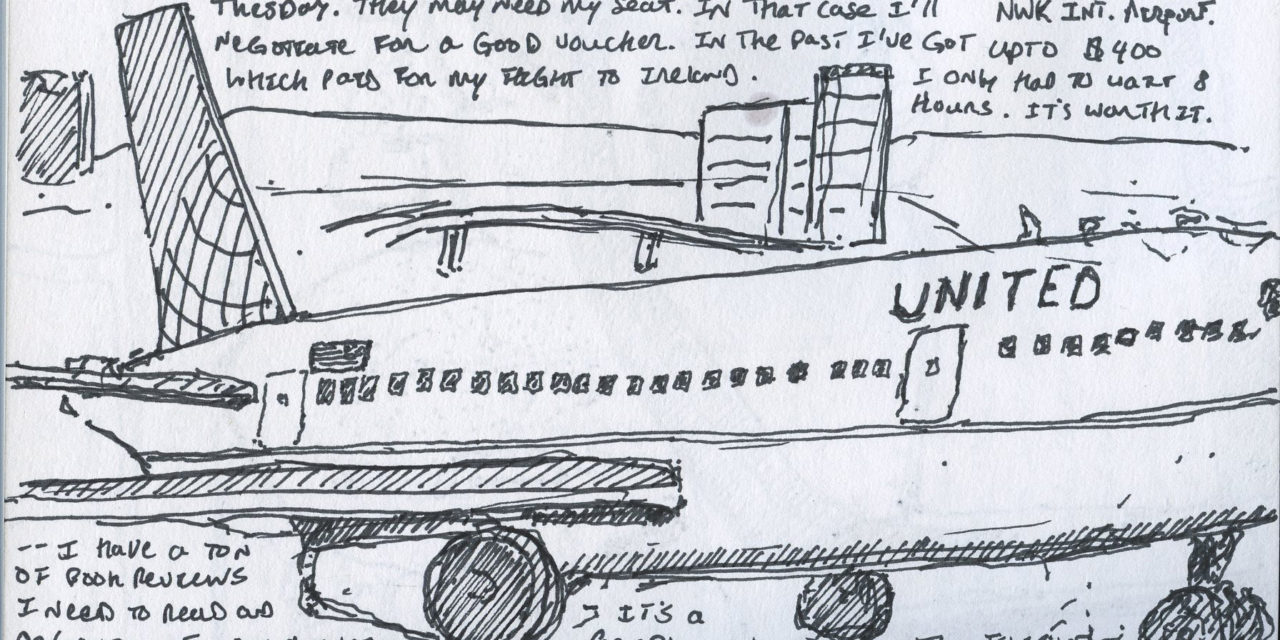

The first page in this series actually begins before my trip. I came down to New York City from Ithaca in a friend’s rented car. From New York, I traversed a complicated system of interconnected train lines – MTA subway to Port Authority Trans Hudson to New Jersey Transit — that eventually took me to my parent’s home in suburban New Jersey. I went out dancing in the city that, and I don’t think I had yet slept at 10:30 in the morning when I wrote lovingly of the Pulaski Skyway. It currently stretches over a vast marshland of tall yellow grass, and mammoth rusty warehouses. “I look forward to this part of the trip every time” I wrote. Despite Jack Kerouac’s characterization of this land as the “armpit of America,” I find it a very pastoral and human part of New Jersey. At any given point you might time-trip to a forgotten preindustrial era with nothing but fields, swamps, and narrow streams that empty into larger bodies of water. Then suddenly you notice a thin black metal cloud emerge from the horizon, which floats forever beyond your view—this is the Skyway. The abandoned warehouses are hollow cathedrals. Their peaks reach more than a hundred feet in the air, and stretch out horizontally twice that distance. The former DuPont chemical site on the outskirts of Newark always leaves me with sadness, and curiosity. It’s all lovely yet creepy in a decrepit, and cancerous sort of way. How will this scene change over the next ten or twenty years? What will the next generations see?

I spent a lot of time at High Tide Cocktails in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. It was pricey as far as dive bars go— $5 for any pint. Was there a happy hour? “Every hour is happy,” the bartender smiled at me, “this is High Tide.” The bartenders were friendly, and by the end of my adventures in SF they greeted me by name when I walked in. The place had a pool table, which is always a plus, and it had charming décor including what looked like an alter to painted women with a feather boa and exposed breasts. What brought me to the High Tide so often, however, were the people. This is the sort of place where middle-age men come to drink heavily after work and complain about their families, or where white middle-class hipsters pregame in the glow of multi-color Christmas lights that hung from the ceiling. I liked the loners, though, the kind you’d find in any local bar, the kind that would sip whiskey alone and watch the Warriors game. They always have a special relationship with the bartenders. I’d like to think I developed one too. High Tide was welcoming because it was a place where people minded their own business. It was perfectly acceptable, for example, for me to order a beer and sketch it as I drank (as usual). I listened to people’s voices, causally jumping one conversation to another. I listened to vocal intonations like I would listen to music. The content of the conversations didn’t matter, nor they make sense without context. It didn’t matter; I soaked in the experience. High Tide was a collection of different accents, though mostly in English. All the bartenders were ethnically Chinese, which made sense since SF is home to one of the largest Chinese communities in America—second, perhaps, only to NYC. Great Chinese food. Egg tarts from the Golden Gate Bakery are cheap, but priceless.

Click on Thumbnail for Full Image

[Not a valid template]