The Stars and Stripes stand to the right of the Ark on the bimah at my local shul in the Chicago suburbs; the Degel Yisra’el, the blue-and-white flag of the State of Israel, stands to its left.

It’s just another Shabbat in the diaspora.

The presence of Zionism and the State of Israel in diaspora Jewish life is so pervasive that, after a while, you stop seeing it; yet it is always there, in the synagogue sanctuary and without. When I was a camper at Camp Wooden Acres and the YMHA Country Camp in the Laurentians north of Montreal,[*] we hoisted the Degel Yisra’el alongside the Maple Leaf Flag of Canada every day while singing “Hatikvah,” the Israeli national anthem. It was so inscribed in my memory by ritual and repetition that I remember the words today – “Kol ‘od balevav penimah…” – even if I don’t know what most of them mean.

All I really knew was that Israel was where my trees were. The Jewish National Fund, the Zionist movement’s largest fundraising organization, has been taking donations from diaspora Jews for decades to plant trees in the names of our loved ones, to mark important life events, or for no special reason. The JNF has planted more than 240 million trees, and four of them are mine. My Zeide, uncles and aunts had trees planted to mark my birth, my Bar Mitzvah (two trees), and my high school graduation. In exchange for their contributions to Zionism, I literally get to put down roots in a country that I have never visited.

The JNF’s Blue Box – a rectangular tin with a coin slot at one end – was, and continues to be, a common feature in Jewish homes, sitting on a kitchen counter next to the refrigerator or on a bookcase. Introduced in 1904, the Blue Box was based on the traditional pushke, an alms box into which Jews would anonymously deposit coins to perform the mitzvah of Tzedaka (charity).

In its JNF form, this pushke was the first and longest-lasting Zionist fundraising campaign, raising millions of dollars over more than a century. “But the Blue Box was more than just a fundraising device,” the JNF notes on its website, “From the beginning, it was an important educational vehicle spreading the Zionist word and forging the bond between the Jewish People and their ancient homeland.”

Indeed, every coin that a Jewish child dropped into the slot was a mitzvah – the fulfilling of a commandment, a good deed – of Tzedakah – literally “righteousness.” Our parents told us that it was “for Israel,” and I suspect few of us demanded more detail.

This blending of Zionism with the tropes of religious observance has produced, at least in the Ashkenazic diaspora, a Judaism wholly focused on the State of Israel in ways strikingly similar to the doctrines and liturgical practice of the First and Second Temple periods. The State of Israel and its secular political leaders demand the ritual obeisance and offerings once reserved for the Kohanim in the Temple sanctuary. It is Third Temple Judaism.

It is a mitzvah, an act of pious righteousness, to support Medinat Yisrael as the political manifestation of Eretz Zion. While from 71-1948 CE Jews davened while facing toward the Holy Land as an idealization of hope and justice, we now turn to the real political entity of the State of Israel, which claims our allegiance.

Indeed, this allegiance is explicitly reinforced in the liturgies of virtually every Jewish diaspora congregation – Reform, Conservative, and Orthodox; Ashkenazi and Sephardi. In one form or another the Prayer for the State of Israel, composed in 1948 by the novelist S.Y. Agnon and endorsed by the Sephardi and Ashkenazi Chief Rabbis of Israel, has found its way into the siddurim (prayer books) of mainstream Judaism. I am most familiar with the version that appears in the Siddur Sim Shalom of the American Conservative movement:

Our Father in Heaven, Rock and Redeemer of the people Israel: Bless the State of Israel, with its promise of redemption. Shield it with Your love; spread over it the shelter of your peace. Guide its leaders and advisors with Your light and Your truth. Help them with Your good counsel. Strengthen the hands of those who defend our Holy Land. Deliver them; crown their efforts with triumph. Bless the land with peace, and its inhabitants with lasting joy. And let us say: Amen.

This was just as it should be for my father’s generation. The Holocaust and the devastation of the Second World War had created a humanitarian crisis of unimaginable scale. A quarter of a million Jewish survivors of the Nazi death camps were crowded into makeshift Displaced Person facilities in Germany, Austria, and Italy. At least a million more Jews were refugees, on the run and on the road from the Pyrenees to Volga River. They could not return home to Paris, Berlin, or Jedwabne after their Gentile neighbors had looked away when the trains came, or sold them out to the Gestapo – or worse. And the victorious allies – the United States, the Soviet Union, and the British Empire – were no more inclined to open their doors to Jewish refugees in 1945 than they had been when the Holocaust began.

These were our people, and they needed a home. Israel gave them a home.

For the diaspora Jews of 1948, the State of Israel was a kind of miracle, the fulfilment of a long-delayed promise, if not exactly a biblical prophecy. In the shadow of the crematoria smokestacks, and the very recent memory of the bodies “piled like cord wood” at Auschwitz, Sobibor, and Belsen, Israel offered hope that the long millennia of antisemitism and murder were at an end. The image of young Sabras in bucket hats singing “Hinei ma Tov” while they built Tel Aviv in a night and made the desert bloom represented a kind of high idealism and a salve for the pain of recent history. Diaspora Jews’ attachment to Israel was not a question of politics or allegiance, they told themselves, it was simply a mitzvah.

The extent to which the enlistment of the diaspora Jewish community in the Israeli national project was ever fully apolitical even in 1948 is a question of much debate. But today, almost 71 years after David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the Israeli Declaration of Independence at the Tel Aviv Museum, there can be no doubt: whether or not diaspora Jews believe that their allegiances are divided, the Zionist movement and the State of Israel demand it, and invest vast effort and resources to obtain it.

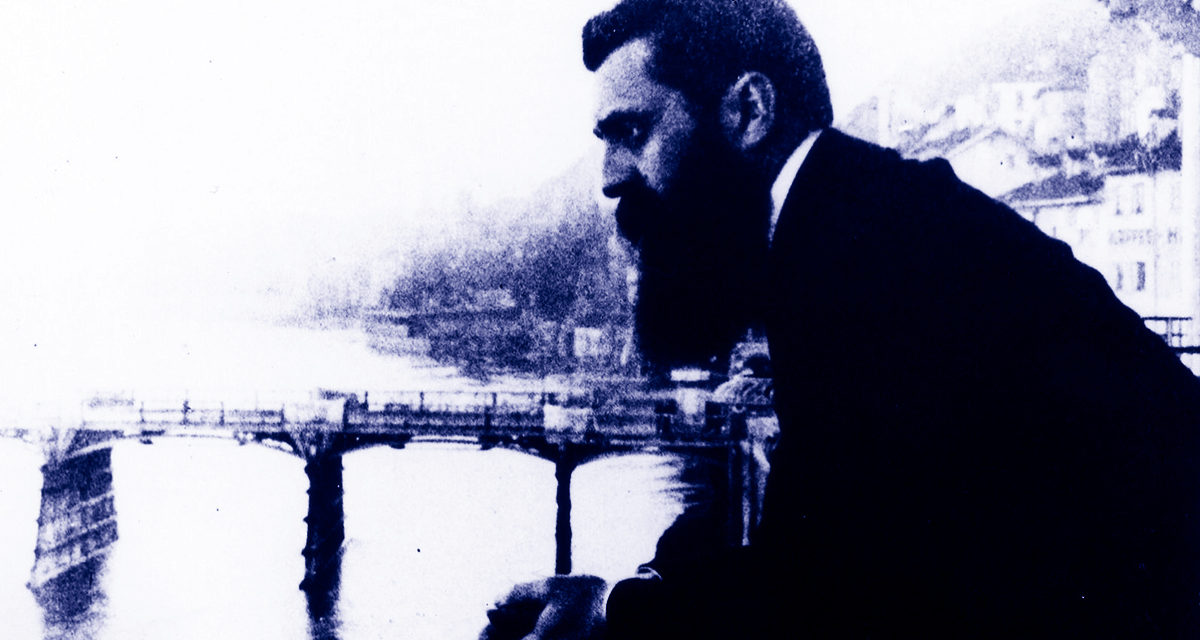

The Zionist solution for antisemitism had always been the ethno-nationalist gathering-in of Jews to Israel and the negation of the diaspora. In his 1896 pamphlet Der Judenstaat, Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement, expected and even welcomed the extinction of the diaspora Jewish community – those Jews who did not accept the invitation to the new homeland – through assimilation. “For they would no longer be disturbed in their ‘chromatic function,’ as Darwin puts it, but would be able to assimilate in peace, because Anti-Semitism, now active, would have been stopped forever.”[†]

This, the central proposition of Zionism, thus regards diaspora Jews as either Israelis-in-waiting, as unnecessary refuse to be discarded, or as useful agents for the advancement of Israeli interests abroad. The government of Israel has a senior cabinet ministry for Diaspora Affairs “entrusted with fostering the connection between world Jewry and the State of Israel, through joint activities and ongoing dialogue, since the Israeli government sees itself as being responsible for all Jews worldwide, whether they live in Israel or the Diaspora.”

Through this department and the Ministry of Religious Services, the State of Israel spends hundreds of millions of dollars annually, helping to fund Jewish education, summer camps, the training and certification of mashgichim (religious officials charged with ensuring dietary law compliance) and, above all, the organizations and institutions of the official diaspora Jewish communities. The current Diaspora minister, Naphtali Bennett, has introduced a proposal that would increase spending on diaspora day schools and summer camps to 1% of the Israeli government budget, about $1 billion annually.

The Ministry of Diaspora Affairs is the propaganda arm of the State of Israel in the global Jewish community, but it goes much deeper even than that. Virtually every establishment institution of diaspora Jewish life receives support, financially, institutionally, and through joint ventures, from the Israeli government. In the United States, these include the American Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Conference, B’nai B’rith, and the mainstream rabbinical colleges. Indeed, the Jewish Federations of North America, the diaspora’s largest umbrella organization, was formed out of the merger of the United Jewish Appeal and the United Israel Appeal. The establishment institutions of American Jewish life are deeply enmeshed with Zionism and the interests of the State of Israel.

This is significant because one arguably cannot be a Jew without a Jewish community – and this allows the large, well-organized, well-funded establishment institutions to exert a powerful hegemony. If you go to a Jewish summer camp, you will go to one run by institutions like JNFA, Federation CJA (in Canada), and B’nai B’rith. When diaspora children go to Hebrew school, to learn the language of the Torah and prepare for Bar Mitzvah, they study from books published by the Jewish Publication Society, and subsidized by he JNFA and the Israeli government.

Buying Yahrzeit candles, or Matzah for Pesach, or shopping at a Kosher bakery, involves interactions with all of the Jewish regulatory organizations funded and supported by Jewish community institutions like the JNFA. And when you are nailed into a pine box and lowered into the ground while loved ones say kaddish, it will be at a Jewish cemetery subsidized by a Jewish community institution, under the eyes of a rabbi trained at Hebrew Union College or the Jewish Theological Seminary, or some other large rabbinical college subsidized by the Ministry of Religious Services.

It is unavoidable. To be a diaspora Jew is to be in constant contact with institutions and organizations the State of Israel cynically and persistently leverages to promote its hegemonic interests.

Writing in response to Rep. Ilhan Omar’s comments last week that Israeli activists “push for allegiance to a foreign country,” Jonathan Chait noted in New York Magazine that the accusation of divided loyalties is an old, antisemitic canard. Taken in isolation, the charge that those Jews can’t be trusted because they are only really loyal to Israel reeks of the old libel of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Yet in their persistent and sustained efforts to extend and maintain their hegemony, Israel and the Zionist movement do claim the divided allegiance of diaspora Jews, and the Basic Law passed in the Knesset last summer that proclaimed Israel to be the nation-state of the Jewish people merely embodied in Israeli constitutional law what Ben-Gurion had proclaimed in 1948: the State or Israel explicitly demands the allegiance of all Jews, wherever they reside.

So, considering that Israel receives more than half of US foreign military aid and that it has managed to obtain Washington’s bipartisan political acquiescence to brutal imperialistic policies in occupied Palestine that would spark outrage if it were any other country, it is not unreasonable to ask if the edifice of Israeli influence in the diaspora Jewish community might have something to do with it. Rep. Omar is right to ask.

This question forces diaspora Jews to confront our Zionist problem: Israel’s cynical manipulation of our communities only aggravates the myth of a Zionist conspiracy and places us under suspicion, while routinely implicating us in atrocities committed in our name. Perhaps the time has come to take the Degel Yisra’el off the flagpole and reclaim our allegiance.

***

[*] In the interests of full disclosure, my father, Joe Friedman, was the director of both.

[†] Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (New York: Dover Publications, 1988), 80.

***

Photo: Theodor Herzl during the First Zionist Congress in Basel. Switzerland, 1897, by E. M. Lilien.